People living in rural areas are often assumed to be more likely to distrust the political system than those living in cities and towns. But is this really the case? A new analysis from Lawrence McKay, Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker finds that at the global scale, it is urban areas that tend to exhibit lower levels of political trust.

Populism, authoritarianism and lack of trust are an unholy trinity of problems for liberal democracies today. Researchers of trust have long held that it is a vital resource for democratic societies, ‘oiling the wheels’ of policy processes and public co-operation with laws, regulations and guidance from authorities and experts. Research suggests that political trust has waned in many countries, such as the United States, prompting talk of a ‘trust crisis’.

It is often argued that there is a geographical dimension to this problem: a ‘geography of discontent’. As economists discuss, the benefits of growth in a ‘neoliberal’, globalised era have largely accrued to educated city-dwellers, while rural areas have depopulated and seen traditional industries decay. This discontent, it is argued, has caused a backlash contributing to the rise of Trump, the Brexit vote, European populist success and rural populism in developing countries.

In our view, it would be a mistake to treat this debate as settled without careful comparative study. One major problem is the use of a handful of Anglosphere and European countries to support an argument that is often global in scope, or at least seen as applying to developed countries as a whole. A series of studies of specific European countries and across Europe in general find higher political discontent in the countryside.

Studies of Africa and Latin America, however, suggest the opposite – though these are not comparable in survey timing and wording. In a new study, we fill an important gap: a global, comparative study of the urban-rural divide in political trust. Our findings challenge the consensus: we find evidence of a profound trust problem in urban areas, and Western Europe is unique among European regions in its rural discontent.

Applying theories of trust

Our theoretical expectations are drawn from the classic ‘competence, integrity, benevolence’ model of trust. Citizens who saw the system delivering growth and effective public services (competence), avoiding scandal and corruption (integrity), and projecting a sense of caring for their welfare (benevolence) would be most likely to trust. Following previous literature, we anticipate that in developed countries, weak growth, public service gaps and a lack of pro-rural electoral appeals would indeed lead to rural areas being lower in trust.

However, we expect a different picture for developing countries. While rural areas might still have worse state provision, their expectations may be lower and easier to satisfy, projecting competence. Clientelistic social relations in the countryside might provide evidence of the benevolence of powerful authorities. Finally, people in urban areas would be more connected to digital and social media that expose elite wrongdoing, undermining perceived integrity. As a result, we predict that in the developing world, it would be urbanites that were more likely to lack trust.

Analysis

To test this question, we conducted the largest and most global study yet of the geography of trust. Our analysis comes in two parts. In the first part, we used only recent survey data, the 7th wave of the World Values Survey (WVS) and a strict, ‘objective’ measure of rurality endorsed, among others, by the UN and OECD, known as the Degree of Urbanisation (DEGURBA). To derive this, we match respondent co-ordinates to a grid dividing the world into 1 square kilometre cells, each with their own DEGURBA classification.

This objective measure avoids the problems of self-reported data, but is only available for 34 countries in the WVS-7 (totalling over 45,000 respondents). Therefore, we confirm our analysis, and test differences between regions, using the Integrated Values Surveys (1990-2020), a combination of the WVS and European Values Surveys conducted over this time. In this analysis, although we rely on an interviewer-coded urban-rural measure (estimated settlement population <5000), we have a massive sample of over 280,000 respondents, in 98 countries.

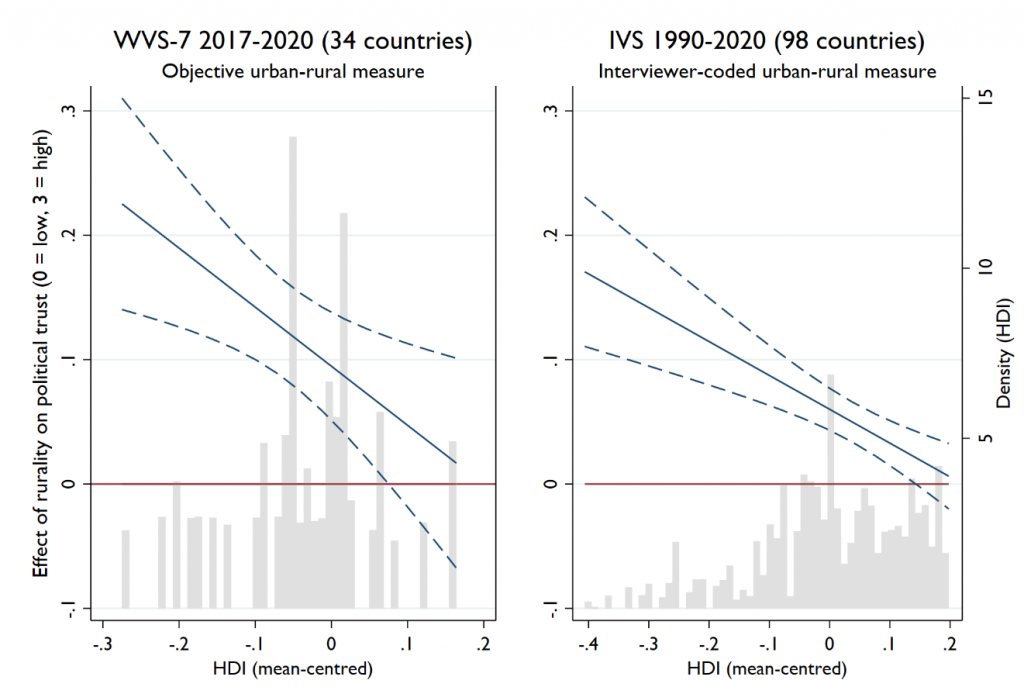

Our dependent variable is an index of trust in government, parliament, and political parties, which we model using multilevel regression, with country-level controls for GDP growth and corruption (two of the main determinants of trust) and individual-level controls for age, income, education, and sex. To test the difference between high and low-development countries, we interact rurality with the UN’s Human Development index. Our results are summarised in marginal effects plots. These show the predicted effect on trust of living in a rural area at a given level of development, with 95% confidence intervals. Above the red line means the effect is positive, and below means negative.

Figure 1: Marginal effect of rurality on political trust by level of development

Both sets of data tell a clear story. On average, across the globe, rural areas are higher in trust. This effect is largest for the least developed countries. As development increases, the effect decreases and fades to zero in the most developed countries. This finding is robust to numerous robustness tests, such as restricting the sample to democracies and using GDP in place of HDI.

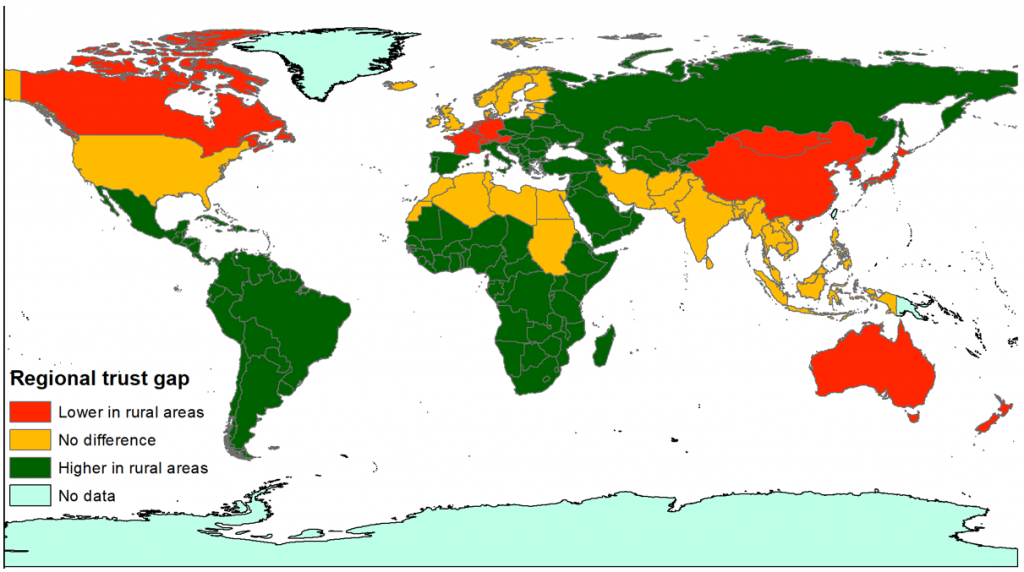

Finally, we explored country and regional variation, exploiting the sheer size of the sample. A key takeaway from this is that not all developed countries are alike. In the United States, we surprisingly do not find lower trust in rural areas, but we do for Canada and Australasia. In Europe, our findings were intriguing. Countries in the South and East are more akin to developing countries, showing higher trust in rural areas. In the North (Baltics, Scandinavia, Denmark, UK, Iceland) there is no difference, but in the West (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland) we do observe the expected pattern of lower trust in rural areas.

Figure 2: Urban-rural trust gap by global region (UN Geoscheme) + US/Canada

What is the geography of political trust? Our tentative answer is that it has surprising characteristics, given conventional wisdom. Trust is generally higher in rural areas of the developing world, while rural distrust may be overstated as a phenomenon in highly-developed countries – albeit with important exceptions, including Western Europe.

The variations within the highly-developed group pose a significant new puzzle: future research should explore the effect of factors such as levels of urban-rural inequality, country-level urbanisation, party of government, and electoral rules. In short, a focus on political factors as well as economic may prove fruitful for researchers.

Our findings also have a clear message for policymakers and international institutions. Just as some populists have found a happy hunting ground in some rural parts of developed countries, there is potential for other types of anti-establishment politics to find a base in the urban developing world – with potentially destabilising effects. The concerns of urban-dwellers, therefore, cannot be ignored in processes of trust-building.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying open access paper at Political Geography

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Adam Borkowski on Unsplash