Covid-19 has presented unprecedented challenges for the EU’s member states. Drawing on a new study, Rahel M. Schomaker, Marko Hack and Ann-Katrin Mandry take stock of the EU’s reaction to the first wave of the pandemic. They write the response was characterised by shifts between forms of centralisation and decentralisation, as well as formal and informal decision-making.

Informality has become a much criticised but important instrument of EU politics over recent decades. Informality manifests itself in many ways, in communication, the exchange of information, and practices of cooperation, but also in the emergence of new informal institutions or ‘arenas’. Informal institutions can arise and exist in both a complementary capacity or as substitutes for formal arenas or policy mechanisms, thus offering coping strategies for dynamic environments by facilitating formality, making it more efficient or circumventing it.

Notably, political structures, processes and outputs cannot simply be classified as formal or informal but are instead situated on a continuum. However, in particular in times of crisis, the focus can increasingly shift to the informal side. Informal arenas can become more prominent, offering more flexibility than formal structures. Despite the EU having several crisis reaction mechanisms (such as the Union Civil Protection Mechanism or the Council’s Integrated Political Crisis Response), in such situations increased informality can be observed with informal channels and arenas filling the existing gaps.

A continuum from decentralisation to centralisation

Centralisation is often thought of as the ‘classic’ response to crisis situations, implying that decision-making centres regularly shift upwards. The key advantages of centralisation in times of crisis not only include the speed and efficiency of decision-making and the reduction of complexity, but also the implicit system of checks and balances between individual views, access to expert information and – usually – high legitimacy for decisions.

However, pre-installed central decision-making forums exhibit implicit weaknesses. The exclusion of relevant stakeholders results in biases, whilst overburdening certain institutions or individuals produces bottlenecks and delays. Thus, decentralisation represents an alternative crisis reaction mode, especially in highly complex crises. In contrast to centralised procedures, decentralisation allows for fast and local reactions.

As for the EU, increasing centralisation in the course of EU crisis governance may imply two key aspects. Firstly, centralisation can manifest itself through the initiation of action, as well as in the long run via an ‘empowerment’ of the respective institution, for instance via an enlarged mandate. Secondly, in the case of the EU, ‘centralisation’ can imply impulses originating from different institutions, as there is no single ‘centre’.

The interplay of both dimensions in the first wave of the pandemic

In the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, much informal and decentralised action could be observed, but simultaneously there were also some tendencies towards ‘institutionalisation’ in the form of formal and centralised initiatives. In the area of public health, for instance, several informal multinational meetings took place and bi- and multilateral agreements on the exchange of data and the delivery of medical devices were cemented. Relevant actions in the field of digital measures were also mostly developed through informal involvement of member states, the cooperation in the context of the eHealth Network being particularly worth mentioning in this case.

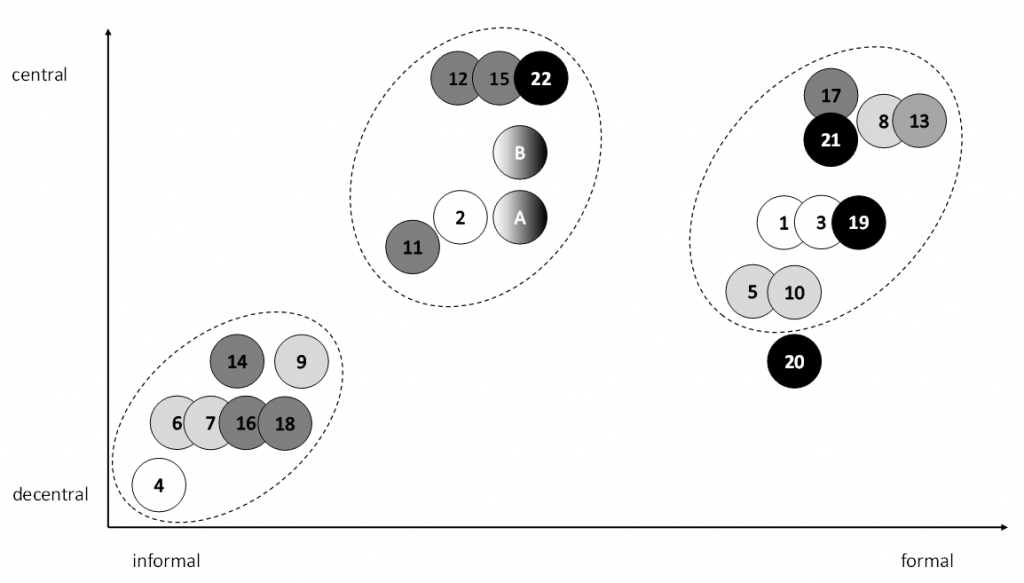

Figure: EU public health and emergency management during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic

First phase (white) – Formal activation of European risk mechanisms, practical action only at the national level (January 2020): (1) Activation of the Early Warning and Response System, first distribution of information by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (9 January) · (2) Informal first meeting of EU Health Security Committee (9 January) · (3) Activation of the Union Civil Protection Mechanism and Integrated Political Crisis Response (28 January) · (4) National return flights (from 31 January)

Second phase (light grey) – First but restrained European action, intensive bi- and multinational cooperation (February 2020): (5) Return flights co-financed by the Union Civil Protection Mechanism (2 February) · (6) Meeting of the health ministers of France, Germany and UK (4 February) · (7) Binational return flights (from 9 February) · (8) Extraordinary Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council (13 February) · (9) Meeting between European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety and health ministers of six member states plus Switzerland, multilateral agreement on exchange of epidemiological data (25-26 February) · (10) First joint procurement of personal protective equipment launched together by the EU and the member states (28 February)

Third phase (dark grey) – First practical effects of formal European risk mechanisms and strong tendency toward centralisation (crisis as top-level issue); however, still important multinational actions (March 2020): (11) Creation of new institutions to avoid shortages of medicines by the European Medicines Agency (beginning in March) · (12) Launch of the Coronavirus Response Team (2 March) · (13) Extraordinary Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council (6 March) · (14) Multinational information exchange between 11 European health ministers · (15) First preliminary meeting of the Commission’s Advisory Panel on Covid-19 (12 March) · (16) Delivery of medical devices agreed bilaterally (from mid-March) · (17) Decision on the creation of the first strategic rescEU stockpile (19 March) · (18) Bilateral exchanges of Covid-19 patients between European countries (especially 22-28 March)

Fourth phase (black) – Important impact of formal European mechanisms, the EU level increasingly takes over policymaking, minor importance of the national level (April 2020 – June 2020): (19) Delegation of medical personnel via Union Civil Protection Mechanism (7 April) · (20) Contract between the Inclusive Vaccines Alliance (France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands) and AstraZeneca (13 June) · (21) Decision of the EU health ministers to transfer the responsibility for negotiating vaccine procurement to the Commission · (22) Presentation of the EU Vaccines Strategy (17 June)

Throughout all phases: (A) Informal coordination between EU agencies · (B) Informal cooperation between the Commission and EU agencies

At the same time, the decision on the creation of the first strategic rescEU stockpile or the delegation of medical personnel via the Union Civil Protection Mechanism showed that formal and more centralised actions represented a decisive part of EU crisis reactions as well.

However, the coordination between the different European agencies included using shortcuts such as informal phone conferences or messenger groups instead of formal coordination mechanisms. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made the crisis Chefsache (a matter for the bosses), creating for example an informal ad hoc committee, the Coronavirus Response Team. This underlines that although centralised actions typically represent more formal ones, in the current crisis the top of the multi-level system also relied heavily on informal modes of policymaking.

Lessons learned

First, while formal arenas for anti-crisis measures do exist, their range was not fully exhausted and the system in place could not develop its full potential. Although the internal coordination between the EU level institutions generally worked well, the formal reaction mechanisms often failed to provide coherent support or coordination to the member states.

Consequently, informality gained in relevance and new channels and informal arenas emerged, such as at the European Medicines Agency. Both within the EU system and between the EU level and single member states, informal and formal action constituted complementary approaches in crisis governance rather than substitutes. An ongoing, subsequent formalisation of informal arenas (such as the creation of the RECOVER project) is conceivable.

A general centralisation trend in terms of a power shift towards the specialised agencies in health and crisis management during the course of the crisis is not evident. Instead, it was the Commission with its (new) President that took the initiative at the central level, at least behind the scenes, partially circumventing existing specialised agencies. Thus, much room for manoeuvre was left to the member states, who often reacted without previous coordination.

However, joint binational initiatives played a leading role as well with France and Germany as key actors. In this context, mechanisms or instruments that have the potential to ‘integrate’ decentralised initiatives might be developed further, for instance via the rescEU system that has to be made fully operational using funds from Next Generation EU and the new multiannual financial framework.

Even if the trend towards informality in the EU seems to have been amplified by the crisis, emerging in both central as well as decentral initiatives, it should be noted that this observed decentralisation did not imply a process of disintegration. The member states have also demonstrated a strong will to create European solutions.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article at the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council