In this contribution, Yunpeng Zhang responds to an earlier post by Qin Shao (see Building Trust and Boundary: Fieldwork in Shanghai) to provoke discussions on the dilemma and ethics of observing, witnessing and writing about vulnerable people. Challenging the ‘boundary’ setting efforts in researching contentious topics and in working with such people, Yunpeng reflects upon his own fieldwork research on Shanghai’s Expo-induced domicide, relating in particular to an episode that revolted his own subjectivity and agency. It is suggested that we take a radical path that views ourselves not as academic professionals but as persons with a particular set of knowledge, and that this way of thinking pushes us to ponder our civic and intellectual responsibilities for the people not as research subjects but as fellow citizens, writes Yunpeng Zhang.

Let me start this short reflection on fieldwork dilemmas with a vignette.

On a windy afternoon in early April, I was on my way home before a thin woman intercepted me and asked me if I would be interested in her experience of forced eviction. After I had spent a month in this neighbourhood, displacees started to recognise me, a liuxuesheng (student studying abroad) working on Expo-induced displacement, but familiarity had not yet developed into trust and easier access. Therefore, I was a bit surprised when she approached me in this way. I cancelled my later appointment and sat with her on a wasted couch inside a bicycle shack.

I made a snap judgement of her age based on her looks: wrinkled and dull face, full mouth of dental implant, grey hair, etc. Therefore, it was a great shock to me when she revealed her real age. “I am now ren bu xiang ren, gui bu xiang gui (half human, half ghost),” she bitterly commented on her stigmatised self, “when I was displaced, I was overweight. Neighbours called me Miss Big. Look at me now.” Her eyes filled with tears when she related to her suicide attempt during the eviction day. Her family of three, collective owner of a private property, was excluded from all negotiation meetings and was not offered any resettlement deal. On the eviction day, she jumped off from the roof of her home as a desperate act of protest. She was rescued but with permanent scars: broken ribs, dental implants, clinical depression. “I feel so unfairly treated. Are they government officers?” She asked me a rhetoric question, “They are thugs. No, they are worse than thugs, far worse.” After saying this, she had a sudden emotional breakdown, hysterically crying out loud in the bicycle shack. It was so sudden and so intense that I felt so unprepared and emotionally incompetent to deal with this situation.

It must be pointed out that crying is not unusual during my interview encounters with the displacees but such private act was mostly confined in private spaces and was far less intense. I was dumbfounded as I was not sure if it was socially acceptable to lend her my shoulder given our age and gender differences, or hand over her a paper tissue and let her vent out her suppressed emotion as a therapist might have done. Also, her cry ripped apart my heart. It was and remains difficult for me to begin to imagine the extent of injustice, humiliation and suffering she endured from losing her home that provoked such emotional collapse in front of a 25-year-old male stranger in a public space. Neighbours soon came down to help both of us, saving her from total breakdown and help me out of the embarrassment. I felt unethical to take a research agenda in her story that day although there were so many gaps in her narrative that I am curious to fill out. For the remaining two hours, I just sat there passively but sympathetically listening to her story punctuated by her occasional weep: “At nights my eyes are always wide open. I have this knot in my heart. It is so aching that I could not fall asleep. My mother passed away last month. I keep dreaming about her and angry at her for not taking me away with her. ”

I felt it an insult to comfort her and help her come to terms with the loss, but that was what I did. I kept telling her that there was still hope in her life and justice would be served eventually. I walked her to her apartment. Her son was also at home that day but refused to come out to look after her. Given her emotional instability, I decided to stay a little longer to make sure she would not hurt herself after revisiting the painful experience of eviction. I tried my best to divert the topics, ranging from dinner plans to recent events I observed in this neighbourhood. Around seven o’clock, she finally calmed down and I arranged another meeting with her, not to satisfy my research interest but to check on her. Upon my turn, she knelt down behind me, murmuring “thank you, kind man (haoren).” Seeing her morality-inversing act I could not hold my tears any longer. Reassured that she would not hurt herself, I fled from the scene.

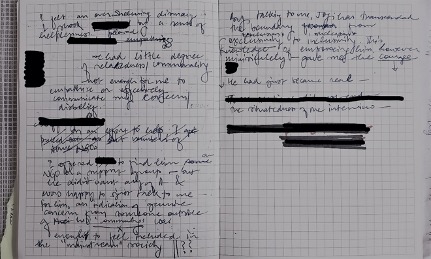

That night when I was jotting my research diary, I kept recalling what I have done that made her feel the need to kneel down to show her gratitude. I did not offer her any material support. Neither did I make any promise to help her seek justice. All I did was to sit there for a few hours, empathetically hearing out her story, not as a researcher but as a normal person would do. This event was a turning point in my fieldwork. Before this epiphany, I had been acting cautiously for my irrational fear of transgressing the political boundary given the contentious nature of my research topic and my UK education background. I recall my over-actions after reading Mayfair Yang’s (1994) comical response of burning her notes for fear of state surveillance before I set out to Shanghai. One of her comments on this episode is that “fear was infectious” (p.22). She certainly made a perceptive point. Her fear from an ethnographic encounter almost two decades ago crept into my mind and locked me into an internalised Bentham’s panopticon. I was over-calculating the political risks before making any political comments or actions, similar to what Lisa Richaud mentioned in another piece on this blog. Such fear became so repressive that it reached a point of draining away all my passion in working on this topic.

Thereafter, I deviated from my original fieldwork plan, threw away the political yokes and became more proactively engaged in political actions, helping the displacees to seek legal or administrative remedies. I offered my assistance to bridge them with western journalists. I helped them to frame their collective actions in moral vocabularies, and sometimes represented them in refuting government officers who attempted to download their responsibility by adopting elitist discourses of “suqiu” (appeal), rights, procedure and legality when I was invited to join their collective petitioning (qunfang). On their behalf, I applied for accessing a bunch of government documents. Against the threat from the local police bureau of grounding me inside the country and charging me of spreading rumours if I publicise my findings indiscreetly, I decided to present their stories at a conference session on displacement and gentrification organised by me in an international conference in Beijing.

I see my actions were spontaneous, not out of my sense of intellectual responsibility given my privileged access to intellectual discourses, cultural capital and political resources, but out of my responsibility as a citizen and as a human being with moral sensibility. Most people I worked with for my project are about the age of my parents or even grandparents. On many occasions when I was listening to their stories or observing their petitions, I was not thinking as a researcher but as a son or a grandson, wondering how I would react if it were my parents or grandparents suffering such horrible injustice, or how would a bystander with civic responsibility would respond when they witness brutal violence against a member of our polity. I felt the strong desire to help or at least to do something, concrete and direct.

The reason I am relating to this event and my actions afterwards is not to narcissistically dramatize my ‘heroic’ fieldwork experience, nor to confess my social incompetency, but to lay bare the “ethical dilemma of witnessing” (Behar, 1996) sufferings and violence, which challenges our positionality and subjectivity as observers in and beyond our fieldwork, unsettles the artificial boundaries that we attempted to maintain, and questions our responsibility as intellectuals in privileged locations, and as citizens and human beings in our everyday life.

As social scientists, whereas we acknowledge the power/knowledge geometries, agreeing that our knowledge on a certain topic is derived from power-laden social contexts, co-produced with the participants we worked with, we also seek to maintain a professional distance, separating us as researchers from them as researched, either out of our research agenda or our intellectual baggage. Whilst we immerse ourselves in the social context of our field sites, we are disciplined to keep our cool, distant, detached and reflexive eyes vigilant, in order to dissect the power dynamics in social interactions, explicate the way power influences the research trajectory and outcomes, and situate them in broader intellectual discourses, after we resign from the social reality (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992). In observing political actions, we are confronted with the ethical concern of exploiting or hijacking collective actions for our own resistance, our political intervention and our desire to make a difference (Blomley, 1994). In our writing in private academic space, we make painful decision in how to represent and depict the lives of others (Crang, 1992). We constantly negotiate our positionality that separates, or connects, our political life outside the academia with our commitment inside a growingly oppressive academic structure and corporate publishing industry (Routledge, 1996). Those are the ethical and political problems we have to confront at some point in our research activity. However, we frequently end up building up what Qin Shao refers to as boundaries that privilege academic publication as a dominant site of our political struggle and our critical intervention to political evils and forget about the elitist nature of our publications.

A greater problematic I am concerned about lies in the split and suppressed person from our persona in our ethnographical encounter with others and in our academic products about others. To phrase it more straightforwardly, how far can we maintain such distance between us as researchers vested with academic interest and us as social actors in a committed, meaningful and reciprocal relation with those we work closely? Is there an ethical limit for our “detached concern” (Emmet, 1967: 160) as spectators or as narrators? I read Qin Shao’s extraordinary work with great admiration for her courage to speak truth to power. Those heartbreaking stories of domicide as documented in such rich details in her book brought me back to the emotionally dreadful moments with the displacees in my own fieldwork on domicide. I believe that the urgency of this kind of scholarship makes any substantial critique of her work counterproductive, therefore, I shall refrain myself from doing so. Nonetheless, the issue I do wish to call for further discussion is related to the photo of an ongoing eviction taken by Qin Shao from another building and her resistance to action research as reflected in her earlier article here.

I felt unsettled by the ethical predicament of witnessing and observing political violence as a fieldworker. I understand her fear of arbitrary state oppression, maybe her sense of powerlessness to stop eviction from happening, and her responsibility and commitment to the overall research project. The controversies I wish to stir up are the questions: is it the most ethical way to observe voyeuristically an ongoing barbarian eviction as a bystander instead of mobilising political resources at our disposal given all the privileges we have in the academia to help or show solidarity in real time? Can our professional role as researchers exempt us from our responsibility and judgement as Homo sapiens who are able to think politically and ethically in violent situations (Arendt, 2003)? By giving away the opportunity to act in real time and place, are we not surrendering our power to the perpetrators, tolerating their actions that inflicting great pains on others, and contributing to rise of a society of bystanders in contemporary China?

To those questions, I do not yet have explicit and mature answers. However, I believe that those questions merit critical reflections, especially when we work with wounded and vulnerable others in violent situations which appeared to become a way of life for many Chinese people. A worthwhile step might be a radicalised politics of our intellectual commitment, as boundary-crossing researchers connect with others not on the level of personas but of persons with transgressive agendas.

Photo credit: Yunpeng Zhao

References

Arendt, H. (2003) Responsibility and judgment. New York: Schocken Books

Behar, R. (1996) The vulnerable observer: Anthropology that breaks your heart. Boston: Beacon Press

Blomley, N.K. (1994) Activism and the academy. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 12: 383-385

Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L.J.D. (1992) An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Crang, P. (1992) The politics of polyphony: Reconfigurations in geographical authority. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space, 10, 527-549

Emmet, D.M. (1967) Rules, roles and relations. London: Macmillan

Routledge, P. (1996) The third space as critical engagement. Antipode 28: 399-419

Yang, M.M.-H. (1994) Gifts, favors, and banquets: the art of social relationships in China. Ithaca, N.Y.; London: Cornell University Press

About the Author

Yunpeng Zhang is a PhD student in Human Geography at the Institute of Geography and Lived Environment, the University of Edinburgh. The fieldwork for his PhD project entitled Better City Better Life? The Fate of the Displacees from the Shanghai World Expo was conducted from February to August 2012. He is currently completing his PhD thesis for graduation in August 2014.

1 Comments