This post presents a project that engaged designers and citizens in the creation of representations – visual narratives, or films – documenting and interpreting urban conditions in the city of Winnipeg, Canada. The intention of the project was that these stories would articulate problems in the city (both physical and social); that the involvement of different groups would contribute to a dialogue about these problems; and that the existence of the films would help develop a shared, if contested, imagination of the city’s potential future, including its urban design. A range of works were created; each fits on a spectrum between urban documentary and storytelling. All share something with urban activist approaches like “photovoice”: contributing to the social understanding of the city, and to our imagination of it. This post takes a critical look at the methods and results of the project, writes Lawrence Bird.

In 2009 I began Beyond the Desert of the Real, a two-year project documenting a North American city in short films produced in the community and with graduate students. The project focused on shortcomings of the urban environment as perceived by residents and recent immigrants. The project was funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), as a postdoctoral fellowship in research/creation. It was carried out in two departments of the University of Manitoba’s Faulty of Architecture: City Planning and Architecture. This financial support and coexistence in two departments leant some validity to the project, but also created other challenges. What is research? Architects and city planners would probably answer this question differently, as would those adopting different approaches within each of those fields. Such differences are built into a project like this. I’m an architect by training, a social scientist and activist by (I suppose) vocation, and a filmmaker and visual artist by inclination. This project brought those interests together, taking the position that the creative synthesis of approaches and methods is a valuable strategy in understanding the city and giving it form.

Filmmaking has been used in social scientific study at least since the work of William H. Whyte (1980). This project was about observation of the city, but it took a different tack from Whyte’s research. For one thing, the films produced in this project were not made by a scientist studying spaces and the populations that used them; they were made by members of that population itself. Rather than recording positive information, the use of space by subjects, they created narratives that told something about how subjects perceived a place. In this the approach shared the acknowledgement by the social sciences of their normative dimension: the social sciences are often aligned with assumptions about value, for example about human rights and the potential for progress. They can produce knowledge which supports such goals, what has been termed emancipatory knowledge. Creative work employs another form of knowledge also: the creation or ascription of meaning. The stories we tell help form how we see the city, just as much as they record our perceptions. At large and small scales, in both our personal chartings of meaning and the intersubjective construction of meaning in negotiation with others, they help form our ideas about the city and they suggest to us how we might change it. They can also provoke political action. So the project aligned with many other uses of visual narrative in urban studies and activism, including the use of “photovoice” in Flint, Michigan (Wang et. al., 2004); and projects like the National Film Board of Canada’s “Here at Home” documenting homelessness in five cities (National Film Board, 2013).

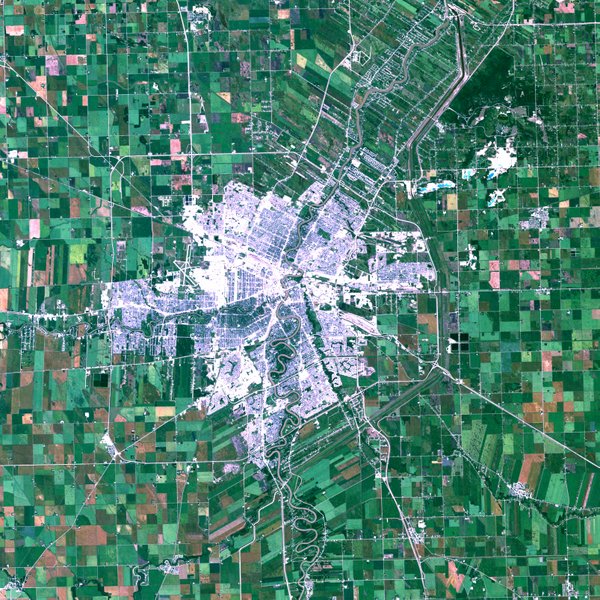

All the participants contributed work focused on the contemporary urban environment of Winnipeg, in the province of Manitoba, Canada. Winnipeg is a mid-sized, Mid-Western city at the geographical centre of North America, about 600,000 in population. Once referred to as “the Chicago of the North,” at the beginning of the 20th century it was a rapidly growing metropolis on one of the main rail routes across North America. Rapid growth at that time, waves of immigration, and policies toward aboriginals which have been termed genocidal, created social conditions that continue to this day. The broad strokes of the city’s urban form – at the confluence of two rivers, and several rail lines – were modified in the mid-20th century by urban sprawl as the city expanded. Like so many other North American centres in the post-war era, its suburbs spread out into the surrounding prairie. Today that expansion continues, albeit slowly compared to larger cities in Canada – Vancouver, Toronto, and Calgary for example. As is true in many other North American cities, the result is a dispersed urban form, in this case a fragmented pinwheel, shot through with pieces of infrastructure that separate its parts at the same time they unite them. The city is a patchwork of uneven development: a historical downtown in decline, suburbs, and terrains vagues (under-developed lands) between. These physical differences tend to correspond to socioeconomic rifts, and a contributor to this is the varied population: over 10% aboriginal including both First Nations and Métis (culturally mixed native and European); and 16% of city residents born outside of Canada. A concern for the fragmented and forgotten physical and social spaces characteristic of this city drove the choice of the project’s title: Beyond the Desert of the Real.

Participants in the project were asked to record this urban environment on video and use their footage to create visual narratives exploring the personal, social and political significance of these spaces, from each participant’s point of view. The equipment used varied from pro-sumer cameras and editing equipment provided by the University of Manitoba, to ubiquitous media like mobile phones. The local media- and film-making organizations Video Pool and the Winnipeg Film Group provided logistical support and instruction in film-making technique.

I worked with two groups in the first year of the project. One of these was composed of graduate students in architecture, who are very much preoccupied with creative activity in their day-to-day lives. The other group might be understood as preoccupied with survival – recent newcomers to the city, all of them immigrants from outside Canada, who were students in introductory and advanced classes in English as an Additional Language (EAL), classes geared toward acquiring language and cultural skills for living successfully in Canada. While these groups were at first imagined as distinct, in fact some of the most interesting work came from participants who fit into both groups at the same time.

The graduate students in architecture participated in the project in the context of several seminars on the history and theory of architecture. Each student produced a short narrative video as part of their coursework. They were asked to make their films part of the critical evaluation of the built environment expected of them as developing designers. To this end we undertook readings in urban and media theory, including Walter Benjamin, Stephen Cairns, Guy Debord, David Harvey, Lev Manovich, and George Simmel. The work produced tended to fall into different categories. Some were extremely personal reflections on life events associated with a particular site or type of urban environment. An example of this was the film A Reenactment of Events, by Rhayne Vermette (at the time an architecture student but now a professional filmmaker), which used animated still photographs and paper models to tell the (true) story of the robbery of a suburban house and the police response, a violation of a different kind.

Other films formed a more clearly social and political critique; for example Space Replaced by Andy Puiatti, which described the transformation of a working-class neighbourhood by developers building on an old school grounds, a former public space. It was told from the point of view of a young architect who had built his own home in the same area and so was, to some extent, himself contributing to the processes of gentrification and development that the film questions.

The second group I worked with consisted of recent newcomers to the city, all adult EAL students from three different resource centres. These students had all arrived in Canada from one to ten years ago. The focus of their work was on whether or not the city’s urban environment worked for them: did the dispersed city make their lives more difficult as immigrants? How did they find the city in light of their experiences with urban environments elsewhere? To help in this process I interviewed the participants with audio equipment, asked them to bring in drawings and photographs to convey their impressions of Winnipeg and cities they had lived in before, and lent them simple flip video cameras on which to record their impressions of the built environment. I helped edit these into short narratives based on their interviews. These films and audio narratives tended to focus on spaces that were personally important to the adult students, played an important role in their lives, and resonated with their aspirations. While many of these students had experienced dense urban environments in their countries of origin, and were aware of the effects of uncontrolled sprawl, they almost universally expressed an appreciation of the resources offered by the suburban built environment. As one student put it, the circle around her home in the suburbs included everything she needed; but she acknowledged that this circle was accessible only by car.

Some of the most interesting work came from participants who could be considered members of both groups. One such member was Zhi Yong Wang, an architecture student recently arrived from China. His film The Lost of Chinatown (see below) depicted Winnipeg’s Chinatown, asking to what extent it might be considered Chinese, if at all. This neighbourhood is located in Winnipeg’s inner city, in lots redeveloped after the decline of the downtown (a decline caused by flight to the suburbs). So Chinatown was an attempt to create a sense of place, in a place that had none. And, from this participant’s point of view, the urban spaces created in Chinatown lack the essential urban qualities he associates with Chinese cities.

The work created in the first year of the project was satisfying in many ways, but left many issues and questions unresolved. One is simply technical; graduate students in architecture are adept at making things. They mastered film-making techniques quickly and became quite accomplished at telling pertinent stories visually. The EAL students required more support in this, including my involvement in the filmmaking, which raises issues of interpretation. If I contribute to a film, is it theirs? Or do my understanding and opinions of the urban environment infiltrate their stories?

Another issue was the division in perceptions of the city between the young designers and the recent immigrants. While the first were trained to be critical of their environment, perhaps overly so, the second group embraced it. This might have been a reflection of time limitations given the technical gap between the participants; there was less time to develop a critical voice with the EAL students. The newcomers did make critical comments about some aspects of the urban environment, but their works focused on areas they loved rather than sites they disliked or feared.

Another shortcoming of the project is the absence of an aboriginal voice. Winnipeg can be characterized by both the presence of recent immigrants and a very strong native presence, particularly pronounced today in the visual arts and filmmaking communities. Some of the architecture students in the project were aboriginal; Rhayne Vermette for example is Métis. But because of the need to focus the subject group, none of the community engagement work involved native subjects. While the project never aimed to represent all demographics of the city, this is still a failing. The urban aboriginal experience is crucial, both from the point of view of the native experience of the city (in many cases as newcomers arriving from reserves in rural areas), and in terms of the political and social impact of native presence in the city. First Nations have a growing impact in the world of real estate development, as investors. Also, as significant areas of the city fomerly in the control of the federal government (the Department of Defense) return to native ownership, their role as landowners will be more acutely felt. My hope is that some of the methods explored in this project may find applications in aboriginal planning as that field develops as an area of research and activism.

There were ethical issues involved in my work in the community, which impacted on the ability to carry out and disseminate the research. Canada’s ethics guidelines for research into human subjects (Tri-Council Guidelines) understandably insist on anonymity of interviewees in most cases and on allowing subjects a great degree of control over research processes and products. As the EAL students I was working with were, while enthusiastic participants, insecure about their command of English and understandably protective of their privacy (and their neighbourhoods), it was difficult to convince them to let me publicize their work outside the classroom. For these reasons I have been unable to disseminate their work except for a few still images. Architecture students in contrast are eager to have their work made public. This suggests perhaps other fundamental differences between the groups I worked with.

Some of these issues might raise questions about the compatibility of the research products that came out of this part of the project. Nevertheless, the city is composed of different kinds of people, as Aristotle said in The Politics. To cite a source closer to us in time, Jules Dassin’s film The Naked City concludes with the observation that there are eight million stories in the city. In Winnipeg, there are 600,000 different stories. One point of this project was to construct a means of articulating a polyvocal city, in which diverse concerns, preoccupations, and reflections on living in an urban environment could be given voice in a collection of interrelated works. The creation of these films was one means of achieving this. Others were explored in later phases of the project: projection of the films in public spaces; their integration as elements in a gallery installation; and urban design proposals, informed by the films, developed with local architects and landscape architects. But the first step on that route – to designing the city – began with this project on its representation.

References

National Film Board (2013) interactive website http://athome.nfb.ca/#/athome (accessed July 20, 2014)

Wang, C. C., Morrel-Samuels, S., Hutchison, P. M. , Bell, L., Pestronk, R, M. (2004) Flint Photovoice: Community Building Among Youths, Adults, and Policymakers. American Journal of Public Health 94(6): 911–913

Whyte, W. (1980) The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, D.C.: The Conservation Foundation

About the author

Lawrence Bird is an architect and urban designer by training. He studied at the LSE Cities Programme (M.Sc. CD+SS, 2000), and has practised and taught design in the UK, the USA, and Japan. He currently works as a designer on transit-oriented (TOD) urban infill projects in Winnipeg. His dissertation examined the image of the city in film (Ph.D., McGill 2009). He also has a visual arts practise focused on moving images of the city and geography, contributing the projection Transect at Digital Research in the Humanities and Arts (DRHA), University of Greenwich, September 2014. He writes and edits on media, architecture and the city. Please visit the links below for more information on his works.

http://vimeo.com/lawrencebird (creative)

http://www.furtherfield.org/user/lawrence-bird (interviews on art and society)

Related publications

Bird, L. (2014) Beyond the Desert of the Real: Regenerative narratives in the cityscape, in Emerging Landscapes, Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate

For citation: Bird, L. (2014) Art in the field: harvesting visual narratives in the dispersed city. Field Research Method Lab at LSE (21 July 2014) Blog entry. URL: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2014/07/21/art-in-the-field-harvesting-visual-narratives-in-the-dispersed-city/