by Temelso Gashaw

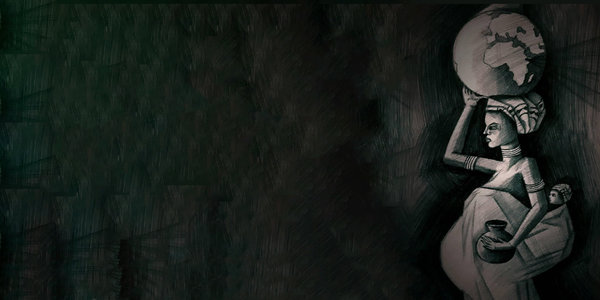

Image credit: Yohannes Moges Belay

International and regional human rights law—including the CEDAW, the ACHPR and the Maputo protocol—calls for transforming customary and traditional practices that violate women’s rights. But unfortunately, women continue to be discriminated against, marginalized and subjected to harmful traditional practices which are embedded in the social fabric since time immemorial. The pervasiveness of practices such as Female Genital Mutilation, polygamy, honor killing, marital rape and the like expose millions of African women to grave human rights violations and have put them in disadvantaged positions for centuries. In most instances, an attempt to prosecute perpetrators of these practices would fail mainly because the law is charged with conserving the cultural values and traditions of the community. Efforts to outlaw such discriminatory and harmful practices have also been equated with submission to neocolonial attitudes or failure to consider cultural sensitivities of the African society. In its extreme form, such lines of debate are often based on the premise that culture and tradition should be protected as the sole source of validity for any global moral order with respect to human rights. Proponents of universalism, on the other hand, argue that “the contents of human rights are universal and apply to every person irrespective of culture.” In this blog post, I will explore and analyze how and to what extent the African human rights system attempts to accommodate both the doctrine of universality and cultural relativity in the context of African women’s rights by comparing the two main women’s human rights instruments in Africa – most notably the African Charter on Human and peoples right (ACHPR) and the Maputo Protocol.

The Cultural Relativism/ Universalism Dichotomy

It is common to hear from African scholars that the notion of human rights is a purely Western construct which does not consider African communitarian disposition. Even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which has attained the status of customary international law, has been criticized for the limited participation of African countries in the drafting and deliberation process. Indeed, these adverse reactions cannot be lightly dismissed since African values are poorly represented in the declaration and most, if not all, African countries were under Western colonial power during the formation of UDHR. However, this can’t be the basis for questioning the validity and significance of human rights standards, neither can this be the reason to detract from their universal enforceability.

For strong Universalists such as Howard-Hassmann, human rights should be the only standards by which we can weigh the validity of certain cultural norms. It follows that any cultural tradition which is not compatible with human rights standards ought to be cast aside. Less radical universalists like Stewart endorsed an evolutionary approach that allows cultures to evolve and change with time. On the opposite side of the spectrum, strong cultural relativists claim that “all culture and value systems are equally valid”. Consequently, the moral codes of each society ought to be the principal source of validity for universal human rights. In the same vein, relativists alleged that culture should take precedence over any other collective international moral judgments.

From a more critical point of view, universalism is perceived by some as nothing short of cultural imperialism and an attempt at homogenization that is oblivious to genuine cultural nuances. However, there is also a concern that the arguments of cultural relativism are open to abuse by fundamentalists, economic and political elites (who are already in the position of privilege), and authoritarian governments. Indeed, “culture” can be misconstrued as a justification to avoid renegotiation of well-established patriarchal social structure and can be brought to bear as a convenient excuse to sustain the existing power relation which exacerbate the precarious situation of women in Africa.

Women’s Rights and Recognition of Culture and Tradition in the ACHPR

African women have broken through multiple layers of alienation and repression. However, most African women are denied the equal enjoyment of their human rights, because of patriarchal traditions and customs. Cognizant of this fact, Article 2 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Right (ACHPR) proclaimed that the enjoyment of rights provided in the charter shall not be discriminatory based on, inter alia sex. In the same token, Article 18(3) of the Charter imposes an obligation on signatory states to “ensure the elimination of every discrimination against women and also ensure the protection of the rights of the woman and the child as stipulated in international declarations and conventions.” However, by virtue of Art. 17 of the same Charter member states are also duty bound to “protect and promote cultural and traditional values recognized by the community”. In addition, Article 29 (7) the African Charter imposes an obligation on every individual to “preserve and strengthen positive cultural values of Africa.” Even though the reference which has been made to international instruments in Article 18 appears to be laudable, it can also be argued that equal recognition of cultural and traditional value is capable of legitimizing harmful and discriminatory practices that would be an impediment to the full enjoyment of women’s rights. It is also worthwhile to mention that the word “positive” in Article 29 demonstrates that the recognition and promotion of African cultural values are warranted so long as these deeds are not antagonistic to the rights of women. Yet again, while the Charter is clear and straightforward with regard to protection and promotion of cultural rights, the issue of Gender equality is not explicitly addressed. Indeed, the main criticism regarding the interplay between culture and women’s human rights in the framework of ACHPR is the latter’s failure to safeguard women’s rights independently rather than conflating within the context of family. The fact that their right is situated in an article which deals with the rights of the child, the aged and disabled reaffirms the long-held traditional perception of women’s subordination. Provisions guaranteeing the right of consent to marriage and equality of spouses during and after marriage are also absent from the Charter.

Culture and The Maputo Protocol

Despite its considerable contribution in setting global standards of women’s right, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (‘CEDAW’) has certain inadequacies, especially for African women. One of the limitations of the Convention is its cultural insensitivity precisely because of the commonly held understanding that culture and women’s human rights are always mutually exclusive or inevitably at odds as the former is deemed to be a barrier to realization and full enjoyment of the latter. The underlying purpose of the Maputo protocol is to rebut such perceptions by contextualizing the global standards to African local reality through internal dialogue and reform. The protocol, which is ratified by many African countries, is pioneering and transformative in many aspects. Apart from its comprehensive approach, the protocol is also known to be distinct in affording women’s right to peace, inheritance and abortion. Its comprehensiveness goes beyond the ACHPR and CEDAW in addressing the issue of women with HIV/AIDS, women in armed conflicts, elderly women and widows’ rights. Unlike CEDAW, the protocol does not face any difficulty in terms of legitimacy and credibility as it was initiated and drafted by African women themselves.

I believe that the Protocol has remedied weaknesses of both the CEDAW and the African Charter in terms of accommodating universal rights of African women with cultural sensitivities of their community. On one hand, the protocol draws inspiration from global human rights norms through ‘cut and mix’ approach, on the other hand, it has contextualized these global norms to African reality. In that sense, it overcomes universalism/relativism dichotomy in the women’s right discourse. Most importantly, Article 17 of the protocol provides that “Women shall have the right to live in a positive cultural context and to participate at all levels in the determination of cultural policies.” Rather than being a mere subject of the discourse, this provision paves the way for African women to be a part of internal dialogue, active participants in reforming discriminatory traditions and harmful cultural practices which are entrenched in the social structure. From this, it can be inferred that the Maputo Protocol reconciled the doctrine of universalism and cultural relativism to an appreciable extent.

Conclusion

The complex relationship between culture and women’s right should not be framed in an “either-or” fashion. Such formulations consider universalism and relativism as inherently conflicting parallel axioms which may not be compromised within women’s human rights paradigm. However, in an exceptionally heterogeneous continent like Africa, underestimating the role of culture in the development of modern human rights standards could be counterproductive as the former provides credibility and legitimacy to the latter. On the converse side, the transformative effect of global human rights standards over oppressive and exploitive culture and traditions also should not be overlooked. As Faulk has rightly pointed out, hesitation to look at different cultural norms through the lens of international human rights standards would result in “a regressive disposition towards the retention of cruel, brutal, and exploitative aspects of religious and cultural tradition”. From this standpoint, the attempt of the African Charter to reconcile universally recognized rights of women with society’s cultural self-determination appears to be unsuccessful as the commitment to gender equality is much less than the emphasis given to traditional values. The Maputo Protocol, on the other hand, exemplifies how, in the face of profound diversity, the bottom-up approaches anchored in local cultures can be productive in enhancing and reinforcing women’s right.

Temelso Gashaw is an Assistant Lecturer at Mizan-Tepi University (Ethiopia) and a recent graduate of the Human Rights Law LLM programme at the Central European University. Currently, he is pursuing his second Master’s at Dokuz Eylül University. His thesis, “Constitutional Nationalism in Multi-ethnic Society” examines the implication of ethno-federalism on the fundamental rights of internal minorities in Ethiopia.

Temelso Gashaw is an Assistant Lecturer at Mizan-Tepi University (Ethiopia) and a recent graduate of the Human Rights Law LLM programme at the Central European University. Currently, he is pursuing his second Master’s at Dokuz Eylül University. His thesis, “Constitutional Nationalism in Multi-ethnic Society” examines the implication of ethno-federalism on the fundamental rights of internal minorities in Ethiopia.

I like your work Temelso, keep it up brother. greetings from Nigeria.