As the amount of FDIs from emerging economies is rapidly growing, European cities need to adopt new strategies to attracts these investments. With a clear understanding of what motivates these firms to invest in Europe, both a post-Brexit UK and continental Europe have the potential to convert FDIs from emerging economies into growth, jobs and innovation, Riccardo Crescenzi and Arnaud Dyevre write.

As the amount of FDIs from emerging economies is rapidly growing, European cities need to adopt new strategies to attracts these investments. With a clear understanding of what motivates these firms to invest in Europe, both a post-Brexit UK and continental Europe have the potential to convert FDIs from emerging economies into growth, jobs and innovation, Riccardo Crescenzi and Arnaud Dyevre write.

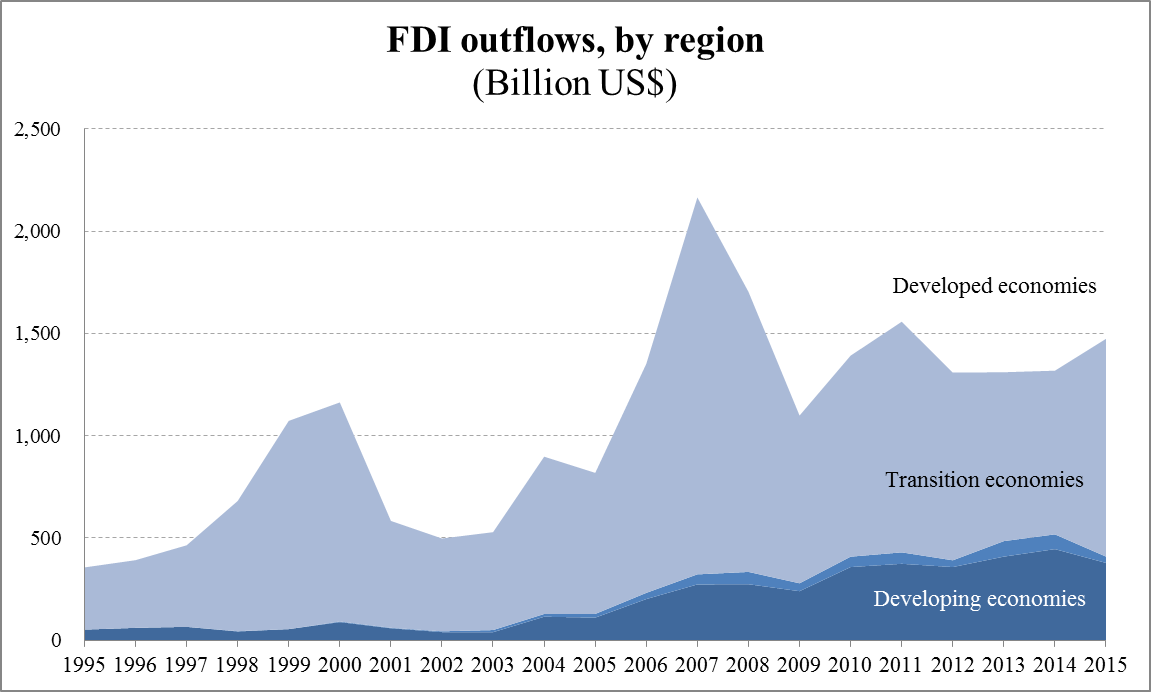

The continuous international expansion of firms from emerging economies has been one of the most striking evolutions of the global investment landscape since the 2000s. This expansion has continued uninterrupted during the global economic crisis. While outflows of FDI from developing economies represented only 13% of the world total in 2007, they now account for 27% of all FDI flows (see chart below). Europe is no exception; between 2009 and 2014 four of the ten biggest foreign investments in the EU were from emerging economies.[1]

Source: UNCTAD Stats

Some of these investments from emerging economies multinationals (EMNEs) have received extensive press coverage. One of the largest FDI projects in Europe in recent years was carried out by the Indian conglomerate Tata, who invested more than US$ 1 billion and created 1,700 additional jobs in Solihull, UK, in 2013. It extended the productive capacity of Jaguar-Land Rover, a company it acquired in 2008.

Understanding the growing appetite of EMNEs for EU cities and regions is of paramount importance to national and local policymakers as these investments have the potential to create jobs and new economic opportunities in the host economies. In a time when Europe (and the post-Brexit UK in particular) is in need for ‘fresh capital’ and new investments, EMNEs are a force to be reckoned with. Until recently, no satisfying answers were provided to the questions: What are the national and regional characteristics that matter most for the attraction of EMNEs investments? Are location decisions by EMNEs fundamentally different from those of multinationals from advanced economies (AMNEs)? If regional decision-makers can better understand EMNE investment drivers and motives they might be able to interact more productively with these new investors of growing global importance and possibly create more welcoming national and regional environments.

Looking at a rich data set of more than 20,000 greenfield FDI projects in Europe—i.e. investments leading to the creation of brand new foreign activities and operations in the host economy—between 2003 and 2008, one can shed light on what makes FDIs by EMNEs different from those of other multinationals. The European Union, unified through its single market but displaying considerable differences across subnational regions, offers an ideal case-study to investigate these differences. Three key pieces of evidence emerge from the data.

First, EMNEs tend to be attracted to EU regions that have higher technological capabilities (as reflected by the local propensity to patent new products), but only when they are conducting abroad high value-added activities such as R&D or design and testing. In contrast, MNEs from more advanced economies tend to prefer technologically dynamic regions not only for their own innovative FDIs, but also for their investment in activities directly associated to production. In addition, MNEs from advanced economies attach a significant value to the socio-institutional environment of their host regions and to the ‘soft factors’ that support localised knowledge exchange and innovation. EMNEs are very different in this respect. Large cultural and cognitive distance makes it difficult for them to ‘de-code’ the nuances of soft innovation factors in European cities and regions.

Second, multinationals from all countries tend to follow location decisions of others. This herding behaviour has been common to many fast growing urban centres: Bangalore for instance, in central India, became the IT hotspot it is today due in part to foreign firms flocking to the region in the 1980s and 1990s. Investing large amounts abroad can be a risky decision and following other firms’ footsteps is one way to mitigate this risk, in particular if they are in the same industry, at the same stage of the value chain or from the same country. Co-location of firms is also motivated by the agglomeration economies that firms can benefit from: they get in close contact with specialised suppliers, they share a larger labour pool and they may learn from other firms via localised knowledge flows. EMNEs in Europe display such imitative location choices, but a distinctive aspect of their investment strategies is that they invest in regions were other multinationals are active in the same business function (e.g. R&D, production, logistics etc.) but not necessarily in the same industry. This signals that EMNEs are particularly sensitive to the local accumulation of knowledge when it is applicable across sectors. EMNEs try to maximise what they can learn from proximity to other multinationals that pursue similar activities while minimising competition from other firms active in their same sector.

Third, EMNEs attach great importance to both regional and national location factors. In the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, regional factors are prevalent while their location choices in all other EU countries are driven more by national common factors.

Ultimately, EMNE investments in Europe are playing an increasingly important role, and this role is likely to be even more central in the years to come. However, cities and regions cannot pursue the same strategies when trying to attract FDI from EMNEs as they did with FDI from the US, Japan or the rest of Europe. Policy-makers should not only reinforce national and regional technological capabilities, but also support the development of ‘institutional bridges’ able to facilitate EMNEs in their understanding of ‘soft’ innovation drivers. Regional and local institutions can play a key role in enabling and accelerating the ‘insidership’ of FDI, in particular communicating tangible and intangible local resources and facilitating access to both codified and tacit knowledge. Helping EMNEs to capture the advantages of the rich national and regional innovation system landscape in the EU might be the key to attract their investment in the most ‘valuable’ activities.

One example of these possible strategies would be to encourage the development of joint ventures between local firms and EMNEs, as well as university-EMNE partnerships. Understanding better the behaviour of EMNEs would allow local policymakers to minimise predatory investment strategies and attract investment projects contributing to local economic development.

This post is based on the article “Regional strategic assets and the location strategies of emerging countries’ multinationals in Europe”, by Riccardo Crescenzi (LSE), Carlo Pietrobelli (Inter-American Development Bank) and Roberta Rabellotti (University of Pavia), published in European Planning Studies (24(4), 2016)

[1] fDi Markets data

1 Comments