By Vito Amendolagine (University of Foggia), Lucia Piscitello (Politecnico di Milano) and Roberta Rabellotti (University of Pavia)

By Vito Amendolagine (University of Foggia), Lucia Piscitello (Politecnico di Milano) and Roberta Rabellotti (University of Pavia)

Foreign investments by emerging market MNEs (EMNEs) are effective in improving firms’ innovation outcomes, but the benefits are lower in ‘global cities’ when compared to more peripheral locations, also due to the fierce competition EMNEs suffer from local incumbents. Drawing on data from 170 investments from Indian MNEs in medium- and high-tech manufacturing sectors, the authors explore the reasons for this difference and how firms might consider entry modes and location choices to maximise innovation outcomes from investments.

The acquisition of Capco, a London-based global management and technology consultancy providing digital and technology services to financial institutions, by Wipro, an Indian multinational company born in Bangalore, is a typical example of a takeover undertaken by an Emerging Market Multinational Enterprise (EMNE) in what the American sociologist, Saskia Sassen has defined as global city. Global cities are major nodes in the internationally interconnected systems of information and money, characterised by a high concentration of specialised businesses — financial institutions, consulting firms, accounting firms, law firms, and media organisations – that facilitate those flows. For a multinational company, the decision to locate in a global city can therefore offer several advantages. First, global cities provide investors with a cosmopolitan environment, which can reduce the so-called ‘liability of foreignness’, that is the barriers, in terms of difficulties and costs, that foreign companies normally face when entering a foreign context. Such an effect is particularly relevant for foreign investors coming from emerging markets as, in addition to liability of foreignness, they also suffer from a sort of ‘liability of emergingness’. Second, the location in global cities can enhance learning and innovation by offering multiple links to novel and technologically advanced economic activities. Third, as global cities rely on good international interconnections, they can facilitate MNEs’ entry into global production and innovation networks. However, choosing a location in global cities also presents some downsides, mainly due to the fierce competition over strategic assets and resources normally taking place in innovative hubs. In fact, this is often a critical issue especially for EMNEs that are often exposed to discrimination and protectionist attitudes in the host countries, thus making their access to key knowledge rather challenging and constraining opportunities to improve their innovation capacity, as shown by Amendolagine, Giuliani, Martinelli & Rabellotti with evidence on a large sample of acquisitions made by Indian and Chinese MNEs in Europe and the US.

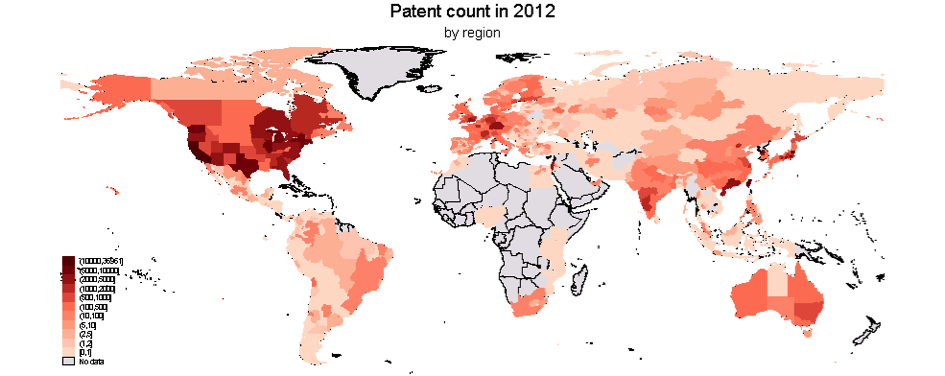

A recent article by Amendolagine, Piscitello & Rabellotti develops an empirical analysis on 170 worldwide greenfield investments (84) and acquisitions (86) undertaken by Indian MNEs in medium- and high-tech manufacturing sectors. They find that the largest share of acquisitions is in Pharmaceuticals and Chemicals, while greenfield investments are more concentrated in Transport Equipment and Machinery. Three-quarters of Indian foreign investments are in high income countries and about 30% of these choose to locate in 31 global cities, such as London, Birmingham and Manchester in the UK, Frankfurt, Berlin, Dusseldorf and Stuttgart in Germany, Barcelona and Madrid in Spain, and Houston and Los Angeles in the US. Further, most investments in global cities in high income countries are – not surprisingly – acquisitions, whereas those in low/middle income countries are greenfield investments and address cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, Bogotá, Istanbul, and Moscow.

As far as the impact of foreign investments on the innovativeness of the Indian MNEs is concerned, the empirical analysis reveals that acquisition of foreign companies – compared to investments undertaken abroad via greenfield initiatives – have a greater positive influence on the Indian investing company’s innovation performance, measured both by the number and originality (i.e., technological variety) of patents granted to the investors in the four years following the investment. However, the analysis also interestingly reveals that when the investment takes place in a global city, as opposed to a more peripheral location, the impact on the Indian MNEs’ innovation performance is lower. One further result is that the advantage of acquisitions over greenfield initiatives, in terms of positive impact on the investor’s innovation output, decreases when the acquired target companies are in a global city. This highlights the importance of jointly accounting for the entry mode as well as the location of the investments to investigate the impact of foreign investments on the investors’ innovation performance.

These findings present interesting implications for EMNEs’ decisions, when they invest abroad to acquire technology and knowledge to improve their innovation capacity. First, foreign investments are indeed effective for increasing investing companies’ innovation performance; second, to maximise innovation outcomes, it is essential to consider both the entry mode choice (acquisition versus greenfield investment, but also other possible modes like strategic alliances and non-equity modes) and the location of the investment. As far as the latter, the location choice should go beyond the country level and include the regional and/or subnational level (for example, global cities, industrial clusters, innovation hubs). Finally, EMNEs trying to access knowledge in foreign countries, and global cities, need to consider the fierce competition by incumbents and local actors including domestic firms, research institutions and other multinationals’ subsidiaries located in the same area.

This article is based on the article “The impact of OFDI in global cities on innovation by Indian multinationals” by Vito Amendolagine (University of Foggia), Lucia Piscitello (Politecnico di Milano) and Roberta Rabellotti (University of Pavia), published in Applied Economics (2022).

Vito Amendolagine is Assistant Professor in Economics in the Department of Economics, University of Foggia.

Lucia Piscitello is Professor of International Business in the School of Management, Politecnico di Milano.

Roberta Rabelotti is Professor in the Department of Political and Social Sciences, University of Pavia.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.