MSc student Mary Diduch details the gap between constituents and those in elected office outlined by Jane Mansbridge in her ‘Listening to One’s Constituents? Now, There’s an Idea’ Brian Barry memorial lecture, held at LSE on Monday 15 May 2017. Listen to the event podcast.

How should elected representatives best communicate with citizens?

It’s an age-old question, one that extends beyond calls to hold more one-off town hall meetings or, in the age of social media, quickly respond to Tweets or Facebook comments from constituents.

Yet it is a question of increasing relevance, particularly following a year where populism and anti-establishment movements appear to have taken hold in Western democratic politics. In the age of globalisation, constituents in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom feel left out of politics dominated by political elites; many point to the failure of established, elected politicians to properly represent them but instead other entrenched interests. In 2016, the United States saw the election of a political novice who appealed to a part of the electorate who railed against mainstream political elites and who vowed to “Make America Great Again.” Last year also saw the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum, with voters choosing to leave the European Union in the hope of gaining more control over immigration and economic concerns that they believe are not being addressed.

Jane Mansbridge, the Charles F. Adams Professor of Political Leadership and Democratic Values at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, tackled the issue of communication and representation for this year’s Brian Barry Memorial Lecture hosted by LSE’s Department of Government.

For Mansbridge, the solution to the gap between constituents and those in office begins with elected representatives. To understand this, Mansbridge looked at where this problem might have originated, with the “crisis of legitimacy” faced by states today.

Increasingly, society has become interdependent and in need of “free-use goods,” which are resources that can be used freely by everyone. However, there will be some who need to contribute to providing such goods, even if there are many who do not. In order to maintain the incentives to do so, Mansbridge said there is a need for more state coercion. Even though there seems to be pushback against such coercion today in the United States and the United Kingdom, as one audience member noted during the question-and-answer session, Mansbridge stated that this growing interdependency shows that such measures more likely than not will only become more necessary. One example Mansbridge provided relates to the environment: A stabile climate would benefit everyone, whether people contribute to achieving this objective or not. Yet accomplishing any goal to ensure a stable climate requires coercive measures — such as regulations and standards — at the international level (an admittedly difficult task). Essentially, state coercive measures help to address the “free-rider problem,” where some benefit from a societal good without paying for or contributing to it.

However, it is clear that states’ capacity to legitimate this coercion is decreasing, according to Mansbridge. Where does this stem from? Mansbridge pointed to some broad causes she sees in the United States and the United Kingdom, such as growing inequality in both countries and the feeling that some in the population have been “left behind.” This can contribute to the sense that politicians are not only corrupt but no longer adequately reflect the views of voters. On top of this Mansbridge noted that we live in a time where constituents are viewing increased state intervention skeptically, and people question authority more readily than they have in the past. This further undermines legitimacy.

So how can a state re-build bridges and boost its legitimacy — its ability to obligate — in the eyes of the people?

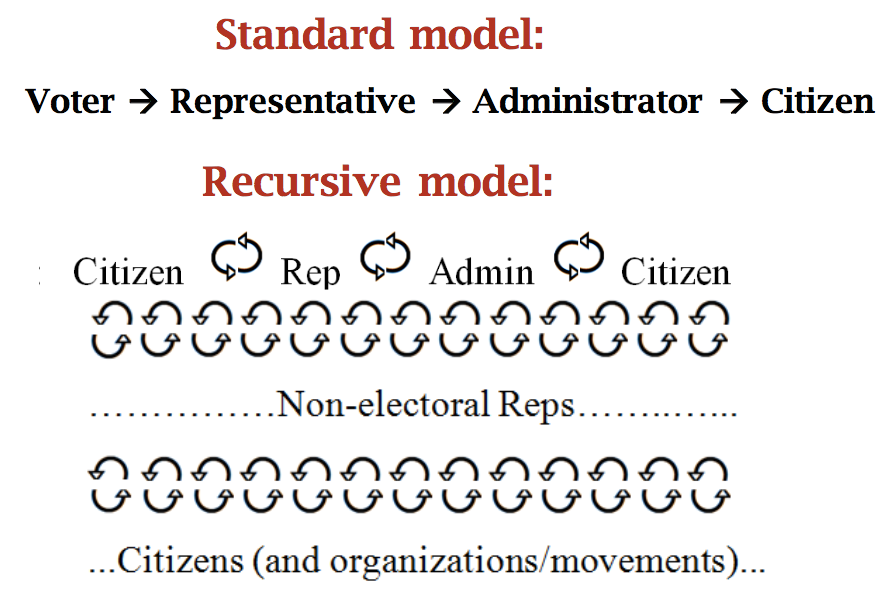

Mansbridge said that it starts with elected representatives, who are in a prime position to tackle this issue as they have been voted into office by the citizens. Typically, communication among citizens, elected representatives and non-elected officials can look like a one-way street. There is little-to-no back-and-forth dialogue among different parties as policies and regulations are shaped and implemented. Mansbridge’s new model of recursive communication instead requires frequent, looping conversations among all groups, with the elected representative as the key “interlocutor” in the process. Such communication calls for each link in the chain conversing with each other over and over, which potentially should lead to ideas and opinions shifting and refining over time as differing considerations are weighed. This does not mean that a representative merely hears out concerns from a citizen; but rather that one person in the chain listens to another, thinks about the comments, and then goes back to the person to discuss any questions and disagreements further.

(image courtesy of Jane Mansbridge)

If such a model already had been in practice, could it have shaped recent political events, such as the Brexit vote on the 23 June 2016? Mansbridge questioned whether representatives were talking with constituents, inundated by media and advertisements, about the vote; whether constituents were talking to representatives about the issues they felt have been most ignored; and, furthermore, whether representatives conveyed the views of constituents within their constituencies. Mansbridge hypothesized that likely, little recursive communication or negotiation was occurring.

And what would be the role in this model for critical voices, such as the media or political parties? Mansbridge, responding to an audience question, noted that it is likely these groups do not fit neatly into this recursive framework. However, in stressing that criticism is important, she said that recursiveness should be seen as an important piece of representation, which is part of a larger system of elements.

Recursive communication does not exist in government today; it is not even seen as a goal, Mansbridge said. However, Mansbridge hopes that this “blooming, buzzing, beehive of recursive communication” can become an ideal to work toward to help restore a sense of legitimacy in government among constituents.

Mary Diduch is an MSc student of Comparative Politics, focusing on nationalism and ethnic politics. Before studying at the London School of Economics, Mary was a journalist in New Jersey.

Mary Diduch is an MSc student of Comparative Politics, focusing on nationalism and ethnic politics. Before studying at the London School of Economics, Mary was a journalist in New Jersey.

Note: this article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.