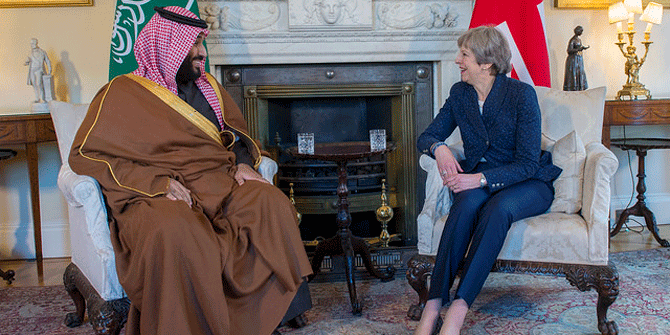

Steffen Hertog reflects on Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman much needed economic overhaul in Saudi Arabia and why the Crown Prince’s plans don’t add up.

Saudi Arabia has moved from political paralysis to rapid action under the de facto leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. He has introduced a raft of ambitious economic reform plans, including the kingdom’s first multiyear fiscal adjustment program, plans for the partial IPO of the national oil company Saudi Aramco, a wide-ranging privatization scheme, and several programs for state investments in new industries. He has swiftly removed his rival Mohammed bin Nayef as crown prince and led a far-reaching anti-corruption purge, leaving old elites stunned — and with lighter wallets.

Like Western investors, the kingdom’s elites are uncertain about what the new order means for the country’s economy. The new Saudi leadership has indeed created new opportunities, but many of the deep structural barriers to diversification remain unchanged. The bulk of the public sector remains bloated by patronage employment, the private sector is still dominated by cheap foreign labor, and private economic activity remains deeply dependent on state spending. Addressing these challenges could take a generation — and it will require patience, creativity, and a clearer sense of priorities.

Saudi Arabia has seen a complete reconfiguration of its ruling elite in the past three years: While a band of Al Saud brothers used to rule collectively with the king as a figurehead, decision-making has now become centralized under one man. Through Cabinet reshuffles and a sudden corruption crackdown, Mohammed bin Salman shocked the ruling family and business elites with his ruthlessness and willingness to take risks radically at odds with the cautious and consensual political culture of the Al Saud clan. While the anti-corruption crackdown was by and large nonviolent, there is no precedent of such a comprehensive purge in any modern Arab monarchy.

The crown prince’s policies may help the country’s bottom line. The Saudi economy faces deep structural challenges, including a large fiscal deficit due to lower oil prices and a private sector desperate for diversification. Centralization of power is required to tackle them — even if measures like the corruption purge showed little outward concern with due process or transparency. Under the new leadership, Saudi Arabia has tackled fiscal reforms more vigorously than most local and international observers expected, introducing unprecedented tax and energy price measures, including the introduction of a 5 percent value added tax, new levies on foreign workers, and increases in electricity and transport fuel prices. The government is now experimenting with new non-oil sectors with an increased sense of urgency, including information technology and defense manufacturing.

Most impressively, the crown prince has begun liberalizing the kingdom’s restrictive social policies. The process started under King Abdullah but has now accelerated. While space for political opposition arguably has narrowed, women will soon be allowed to drive and the religious police force that once harassed them has been almost entirely neutered. By relaxing religious controls over the public sphere, the crown prince is seeking to attract more foreign investment and facilitate diversification into tourism and entertainment.

But the government hasn’t developed a strategy for other key economic issues yet. One powerful constraint is the country’s lack of administrative expertise: The government has only implemented a small fraction of the 543 initiatives in the 2016-2020 National Transformation Program, which was meant to be the cornerstone of economic reforms. Private businesses and technocrats often appear confused over the government’s priorities. New policies and programs are announced constantly, while the delivery capacity of the sluggish Saudi bureaucracy continues to lag. Below the upper echelons, the Saudi state remains the deeply fragmented, bloated, and slow-moving machine that I described in my 2010 book. The government seems to have no clear strategy for reforming this bureaucracy.

Moreover, almost all economic activity in the kingdom is deeply dependent on the state. For decades, the royal family has provided cheap energy to businesses and households as a tool of wealth-sharing, thereby creating inefficient and subsidy-dependent industries. Much to its credit, the government has committed to gradually phasing out subsidies, but the adjustment for the kingdom’s basic industries will be painful. Local economic advisors fear that the majority of private petrochemicals firms — the most developed part of Saudi industry — would lose money if prices of natural gas, their main input, increase to American levels.

More important, public sector employment remains the key means of providing income to Saudi nationals. Cheap foreign labor dominates private sector employment, thereby keeping consumer inflation at bay and business owners happy. Citizens, however, are parked in the overstaffed public sector. Out of every three jobs held by Saudis, roughly two are in government. The average ratio around the world is one in five. Public sector wages account for almost half of total government spending, among the highest shares in the world. Government recruitment has been largely frozen since 2015, but this imbalance will take decades to resolve, even if the government manages to create private jobs for Saudis at an unprecedented pace.

As limits on government employment kick in, young Saudis will increasingly have no choice but to seek private jobs. But they will face tough competition on the private labor market where employers have become accustomed to recruiting low-wage workers from poorer Arab and Asian countries. According to official survey data, average private wages for Saudis are about $2,700 per month, while foreigners earn an average of just $1,000. Reliance on unskilled foreign labor has in turn led to low output per worker and, given the workforce’s limited training, low use of advanced technology across most sectors. Most Saudi products are unsophisticated, yet the costs of production in the kingdom — a country with a fairly high standard of living — are higher than in other emerging economies that produce basic goods. This makes it hard for Saudi Arabia to compete on international markets. As a result, non-oil exports outside of the basic industries sector are very small.

Many Saudis in the private sector also have higher expectations regarding wages and work conditions than the low-cost foreigners who outcompete them. Saudi wage demands will have to drop further if private job creation is to substitute for the erstwhile government employment guarantee. For the time being, private job creation has stalled as the government has pursued moderate austerity since 2015 in response to deficits and falling oil prices.

The government has also underestimated how dependent private businesses are on state spending. The share of state spending in the non-oil economy is extremely high compared to other economies. Historically, almost all private sector growth has resulted from increases in public spending. Through state employment, the government provides the lion’s share of Saudi household incomes, which citizens then spend in the local economy. While private sector wages to foreigners are almost as large as public wages to citizens, foreign workers remit most of that income abroad, so it does not bolster the local economy. Many firms also depend on state contracts; when the government delayed payments to them, it plunged the Saudi construction and contracting sector into depression in 2016, showing what can happen to an economy when the state is the dominant source of demand.

The Saudi government is optimistic about its ability to quickly increase tax revenue without damaging the private sector. But if the royal family wants to avoid a repeat of the recessionary spells of the last two years, it will need to further temper its ambitions to tax households and businesses. As long as oil prices remain below $70 per barrel, the goal of a balanced budget will cause pain for businesses and limit private job creation. This will pose a major political challenge at a time when an estimated 200,000 Saudis are entering the labor market every year. More than 60 percent of the population is under 30, which means that the citizen labor force will grow rapidly for at least the next two decades.

The country’s new rulers recognize that Saudi Arabia’s economy needs to adjust. But promises about rapid diversification and growth could backfire. It would be far more prudent to gently prepare citizens and businesses for a difficult and protracted adjustment period and to focus on a smaller number of priorities. This would make reform easier and allow the government to tackle the major barriers to diversification in a targeted way. It would also enable more reliable communication and coordination with the private sector, large segments of which have been spooked by sudden changes.

The key structural challenge to non-oil growth is the way the Saudi government currently shares its wealth, most notably through mass public employment — an extremely expensive policy that bloats the bureaucracy, distorts labor markets, and is increasingly inequitable in an era when government jobs can no longer be guaranteed to all citizens. A stagnating economic pie that might even shrink in the coming years must be shared more equitably.

The government’s energy price reforms, which compensate households through means-tested direct cash grants, are a good start. The grants disproportionately benefit poorer families, while in the past cheap energy tended to benefit richer families who consumed more. This is good politics as well as good economic policy, as the poor spend a higher share of their income, thereby stimulating consumer demand.

The government could tackle public employment in a similar way. One idea would be to gradually introduce an unconditional basic income for adult Saudi citizens outside of government, financed through savings from further energy price increases and shrinkage of public employment. Saudis could draw on this income to top up their private sector earnings, hence being able to live with lower wages and compete with foreigners more effectively — without imposing high wage costs on local firms and undermining their competitiveness.

A basic income would not only guarantee a basic livelihood for all citizens, but also serve as a grand political gesture that could justify difficult public sector reforms. A universal wealth-sharing scheme would make it easier to freeze government hiring and send a clear signal that, from now on, Saudis need to seek and acquire the skills for private employment and entrepreneurship. The government could supplement this scheme by charging fees to firms that employ foreigners while subsidizing wages for citizens to fully close the wage gap between the two.

Focusing on such fundamentals might be less exciting than building new cities in the desert or launching the world’s largest-ever IPO — but they are more important for the kingdom’s economic future. No country as dependent on petroleum as Saudi Arabia has ever effectively diversified away from oil. The current reforms constitute an unprecedented experiment. The transition will be long and, unless oil prices recover significantly, there will be pain. Distributing this pain in the fairest and least economically distortionary way should be the crown prince’s priority.

This article was originally published in Foreign Policy.

image credit: Number 10

Dr Steffen Hertog is Associate Professor in Comparative Politics in the LSE Department of Government.

Dr Steffen Hertog is Associate Professor in Comparative Politics in the LSE Department of Government.

Note: this article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics