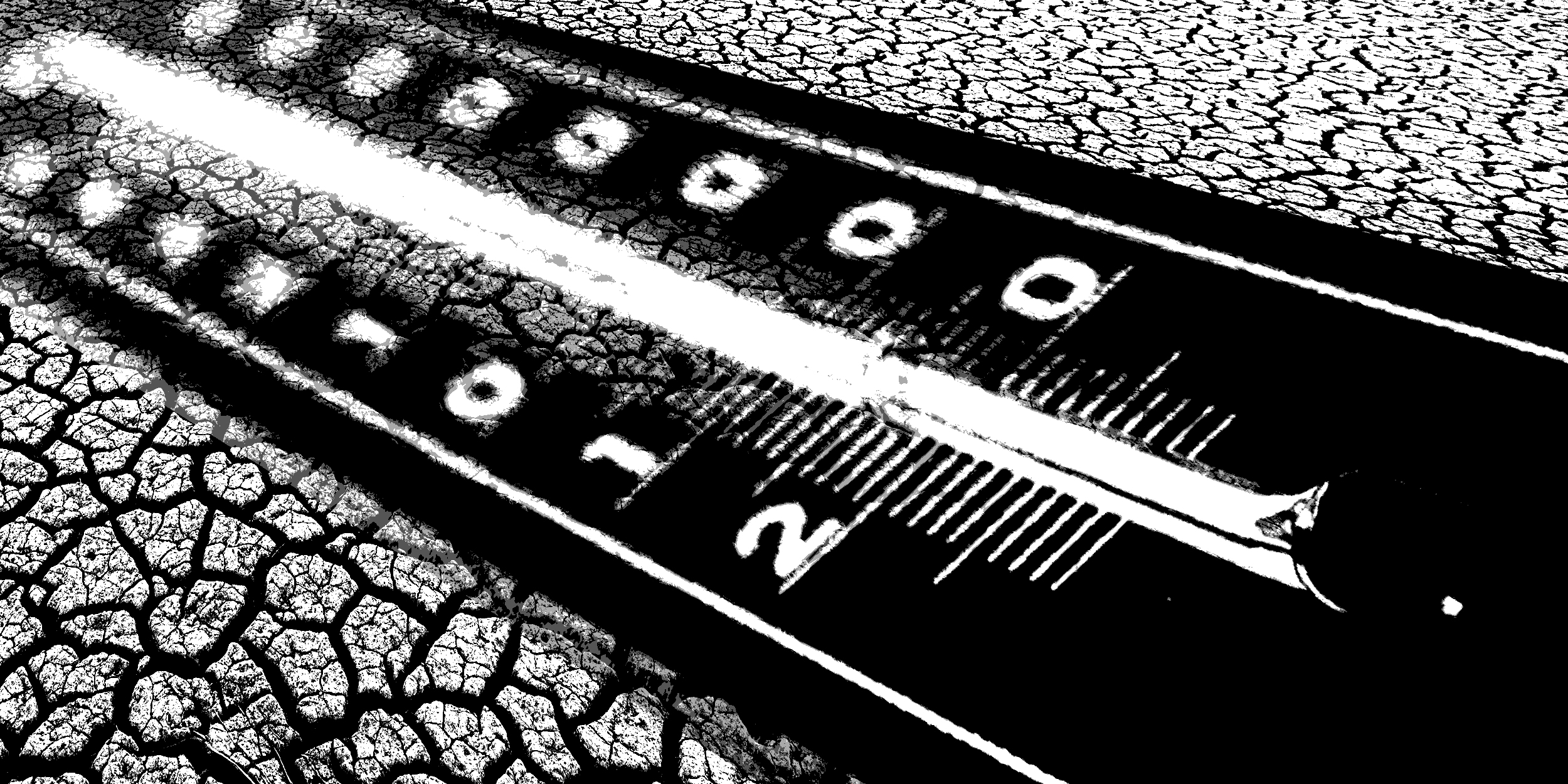

Our students reflect on the COP26 Climate Conference and where it leaves the challenge of tackling the climate change.

“COP26 failed to make even a dent in the challenge of climate change”

“COP26 failed to make even a dent in the challenge of climate change”

Expecting a singular summit to overcome the complex issue of climate change is naïve, yet COP26 failed to make even a dent in the mountain of the challenge ahead.

This is not to say nothing was achieved; gaps in the Paris Agreement were filled in, the Glasgow Pact was signed by over 190 countries, meaning the 1.5C target is still ostensibly in reach. However, if history is to tell us anything, this legislative lip service is likely to mean little in terms of practical change. Indeed, whilst the Glasgow Pact expresses “alarm and utmost concern” at the climate crisis, countries have not committed to phasing out coal. The last-minute watering down of the agreement by China and India further illustrates how the world’s most important powers and biggest current emitters are failing to provide the cooperation needed to manage this crisis. Worst of all, developing nations, who take on the greatest burdens of climate change, were neglected by the summit. The previous pledge to provide $100bn in support was not met according to a UN report, with the new funding agreed still well under what is needed.

These facts, combined with the more superficial frustrations derived from our government officials jetting around in private jets and hypocritically continuing to fund coal production in the UK, leaves me feeling incredibly bleak about our future. The power of protest is incredibly important, but significant change must come from institutions too. How can this be achieved when our leaders are, quite literally, falling asleep at the wheel?

Namitha Aravind is a 2nd year BSc Politics & Economics student in the LSE Department of Government. She works as a freelance journalist and tends to write about British politics, climate studies and intersectionality.

“We can’t rely on those who created the problems to solve them”

“We can’t rely on those who created the problems to solve them”

Governments are recycling their old promises and are committing to making them…renewable. For example, a hundred countries are promising to end deforestation by 2030. An “unprecedented” agreement according to Boris Johnson. However, in 2014, the New York Declaration on Forests was already supposed to halve deforestation by 2020 and halt it by 2030.

A new start can only be based on meaningful agreements and adapted to the emergency. Ending public financing of fossil fuel projects is positive, but the major hydrocarbon producing countries are not part of this agreement. Also, when you look beyond the big statement, you see that in the details one word has been added: “inefficient”. “Inefficient subsidies” will be removed, but not “efficient” ones. What does this mean? On what criteria? Also, we need to focus on the billions of private investments in fossil fuels.

Hoping for a “new start” is to have the illusion that decisions are progressing without understanding that COPs cannot intrinsically drive radical change. The UN COP is not led by a leader, each country has one vote regardless of its size and it must result in a unanimously voted programme, so if a country does not agree, there is no consensus. Far from adopting a binding programme, it is clear that this can only lead to a consensus on the lowest common denominator that each country was already prepared to do before.

It seems clear today that we can’t rely on those who created the problems to solve them.

Féris Barkat is a second year student in Politics and Philosophy in the LSE Department of Government. He is interested in climate policy and environmental justice.

“It’s better to have a platform on which to confront those in power than none at all”

“It’s better to have a platform on which to confront those in power than none at all”

In 2015, I was 13 and living in Paris as COP21 took place. I remember the frenzy and energy that had taken over the city in those few weeks. Now with the end of the Glasgow conference this past Friday, things aren’t quite so optimistic. The past 6 years since the Paris agreement have taught us how difficult it can be to make changes. The impending climate crisis has been turned into a political debate time and time again. One can’t help but feel that this latest COP has only been a demonstration of diplomacy at a large scale.

Things have changed in the past 6 years. The addition of the terms fossil fuels and carbon emissions and advent of policies surrounding coal production are significant. In previous years the concepts hadn’t even been included in the final agreement signed by represented nations. The treaty now asks of countries to gradually “phase down” coal and fossil fuel emissions as we move to more sustainable alternatives. Agreements between the two biggest polluters, China and the USA, also give a certain amount of hope.

However, these agreements show promise but often fall through when it comes to providing a clear plan of action. Many scientists argue these agreements are too weak, making too little impact to change the impending climate crisis. Like Ms. Thunberg, I am of the opinion that these climate conferences are a lot of “blah, blah, blah”, too little meaningfully changes. However, I am also of the opinion that conferences force our elected leaders to make certain promises, and it is our role as citizens to hold them accountable to these engagements. It is better to have a platform on which to confront those in power than none at all.

Liv Kessler is a second year BSc History and Politics student in the LSE Department of International History. Her research interests focus on intersectional feminism and political history.

“What has been done so far is not enough”

“What has been done so far is not enough”

In some ways, important steps forward were taken in Glasgow during the two weeks of COP26. Most prominent among them were a pledge by over 100 countries to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030 and another to end deforestation by the same year. This all sounds like positive progress on the face of it, but some have questioned whether these pledges are really breaking any significant new ground when subjected to closer scrutiny. And you didn’t have to look far to find many of the features that have hampered previous climate summits emerging again.

Some countries, such as Indonesia, signed pledges only to renege them just a few hours later. Richer countries continued to set a bad example by not sending out clear signals of their intentions, as exemplified by the EU’s ongoing internal disagreement on the classification of nuclear power and natural gas as ‘green’ energy sources. ‘The cow in the room’ has been the hugely important topic of the environmental impact of agriculture, which has hardly been broached and no major initiative has been announced to make global food production more sustainable. Lastly, the absence of China’s and Russia’s leaders worryingly suggests that for the world’s first and fourth largest carbon emitters, geopolitical calculations take precedence over the fight against climate change.

Ultimately, most of the negotiations take place behind closed doors away from the public eye so it is impossible for us to determine just how much progress is being made. However, as a Climate Action Tracker report suggests the world is on track to heat up by 2.4°C by the end of this century despite the COP26 pledges, it is clear what has been done so far is not enough.

Pietro Fassina is a third-year undergraduate in the LSE Department of Government studying Politics and Economics. Pietro is interested world history and politics, and passionate about the environment.

Note: this article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.