Adriana Svítková summarises the main findings of her dissertation which examined immigrant attitudes in Brexit Britain.

After the Brexit referendum, EU immigration substantially fell but the net migration of EU citizens continued to be positive, until a drop in 2020, which was explained by the global pandemic. A large amount of research was dedicated to why UK citizens voted for Brexit, but the attitudes of the migrants affected by the vote were explained to lesser extent. Thus, the focus of the dissertation is to examine the attitudes of the largest EU minority immigrants in the UK: Central-Eastern European Union (CEEU) residents a few years after the referendum took place. Featuring in-depth interviews and a survey of over 270 individuals, the research shows that the divide between the ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern Europe’ is very much alive and even more so as a result of Brexit.

The research is not entirely representative of the CEEU population in the UK, particularly due to barriers such as digital literacy or availability. Thus, the dissertation grasped approximately twice as many immigrants in big cities and has featured immigrants who immigrated to the UK for ‘education’ more so than ‘work,’ which is traditionally the most common reason for immigration of the minority. Despite this range, the research brings important insights on the feelings of belonging of this subgroup and their experience of Brexit, giving voice to the often overlooked side of the debate.

Main findings

1. Higher-skilled immigrants do not leave because of the difficulty to get the EUSS

Only a minority of respondents (15%) reported that it was “very” or “somehow hard” to obtain a status under the EU Settlement Scheme (the immigration scheme for EU citizens who have lived in the UK before the end of 2020). Adhering to the new immigration rules did not seem to pose severe administrative complications for the respondents willing to obtain the status, from majority belonging to the highly-skilled CEEU population in the UK.

A few of the respondents are in the UK on visas (2%). Half of these respondents have stated that it was “somehow hard” for them to obtain their visa; although it is a small sample size, it suggests that EU immigration is becoming more difficult after Brexit.

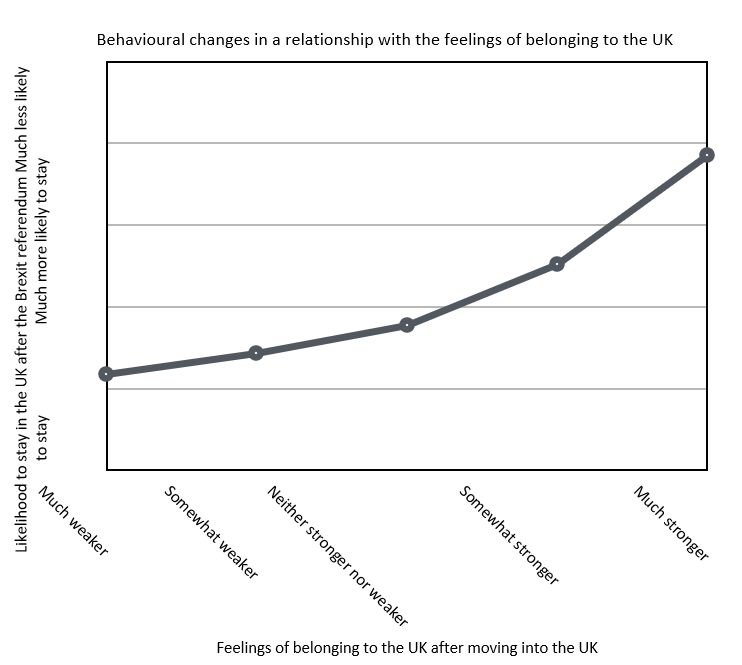

2. Attachments to the UK matter in the decision to remain after Brexit

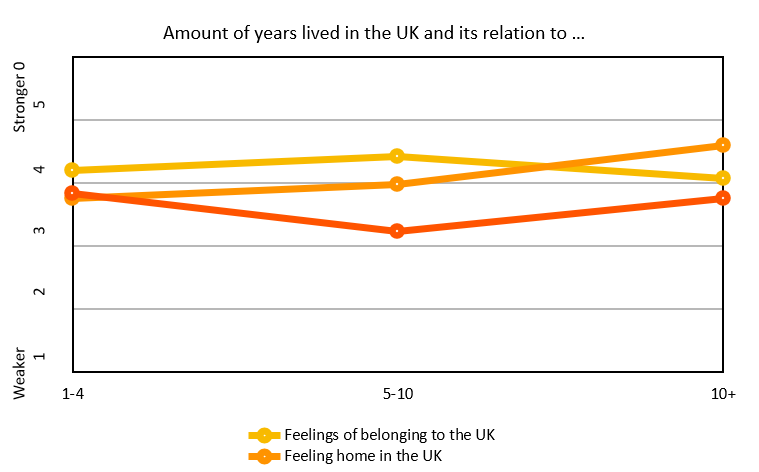

On average, the survey shows that the respondents are somewhat less likely to stay in the UK as a result of the Brexit referendum, mostly because of one’s attitudes, work-related concerns, and family and friends. The least likely to stay are citizens living in the UK under 5 years, with predictably less attachments to the UK. This group of citizens is followed by citizens living in the UK for over 10 years, and only after that by a group living in the UK between 5 and 10 years.

3. A large proportion of immigrants living in the UK between 5 and 10 years are staying for the “everyday”

The motivation of the ‘mid-term group’ living in the UK between 5 and 10 years seems to stem from two interlinked factors: their established ‘everyday’ — their friends, family, and/or job (‘the ordinary’) in the destination country. The feelings of ‘everyday’ are deeply personal and can be also interpreted as the individual’s defiance against the ‘big’ and ‘political’ events such as Brexit. It seems that during Brexit, the familiarity of respondents’ daily routines and networks gave the immigrants a new sense of security; it was the stability of their daily lives that they were striving to maintain by wanting to remain in Britain. Further, this group in particular saw their futures align with the UK, both in terms of educational or work-related opportunities. In a way, the availability of getting an immigration status is used to the advantage of this group, rather than limiting them from staying in the EU.

4. COVID-19 had a less significant effect on the immigrants’ decision to leave the UK than Brexit

In comparison with Brexit, COVID-19 had a much less significant impact on the behavioural changes of the population. Furthermore, it seems that COVID-19 made citizens who had already lived in the UK more likely to stay in the UK long-term, by feeling more related to other UK residents and strengthening their sense of ‘everyday’. Citizens who have lived in the UK for below 5 years seemed to be most apathetic to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, while citizens who have lived in the UK longer mentioned that the pandemic made them “somewhat more likely to stay”. Again, the mid-term group of immigrants seems to be most optimistic about the effect of COVID-19 on their feelings of belonging, building on the observation that this group’s sentiments of ‘everyday,’ including pandemic-related measures, were very strong in the UK. Therefore, the emigration of CEEU citizens is more likely to be ascribed to Brexit than to COVID-19.

5. Self-perception of xenophobia correlates with the length of stay in the UK

The mid-term group is also most optimistic about how welcoming their local community is to immigrants at the time they have lived there, aligning with their strong feelings of belonging. The group living in the UK for under 5 years reports that their local community is welcoming, which can be attributed to the fact that they have moved into the UK after the referendum and hence did not perceive the Brexit Leave campaign to such an extent. The group living in the UK for over 10 years perceives their local community as not welcoming, which suggests that they have most out-lived negative experiences with xenophobia and/or discrimination. However, the data on the experiences of xenophobia/discrimination in the UK show that this subgroup has the weakest perceptions of xenophobia/discrimination. This can be explained by the logic that the more one becomes integrated, the more they weaken their subjective understanding of xenophobia/discrimination and interpret cultural cues differently. In other words, their interpretation of events changes, regardless of whether the events themselves change or not. This would explain why the subgroup still finds the local communities least welcoming, with the weakest perceptions of xenophobia/discrimination.

6. Perceived media misrepresentation of the region led to xenophobia & discrimination of the minority

Among the survey respondents, there was a consensus that the people the respondents have met with in the UK did not understand “their home region” well. Furthermore, those that have experienced xenophobia or discrimination “frequently” or “a few times,” significantly disagreed that immigrants from their country were treated like any other EU immigrants in the UK. This suggests that xenophobia and discrimination were largely connected to the status of ‘Eastern of the respondents — the stigmatised ‘other’ by Western Europe, part of Europe but not quite. In particular, the pervasive discrimination in media had a negative effect on the CEEU integration in the UK, and 60% of the survey respondents stated that the Brexit referendum made them more likely to leave the UK.

Appendix

References

Botterill, Kate, and Jonathan Hancock. ‘Rescaling Belonging in “Brexit Britain”: Spatial Identities and Practices of Polish Nationals in Scotland after the U.K. Referendum on European Union Membership’. Population, Space and Place 25, no. 1 (2019): e2217. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2217.

Giles, Chris. ‘Covid Pandemic Masks Brexit Impact on UK Economy’. Financial Times, 2021..

Ibrahim, Yasmin, and Howarth Anita. ‘Constructing the Eastern European Other: The Horsemeat Scandal and the Migrant Other’. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 24, no. 3 (2016): 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2015.1135108.

ONS (2018). ‘Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality – Office for National Statistics‘, 2018.

ONS (2019). ‘Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality – Office for National Statistics‘, 2019.

ONS (2020a). ‘Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality – Office for National Statistics‘, 2020.

ONS (2020b). ‘International Migration and Mobility: What’s Changed since the Coronavirus Pandemic – Office for National Statistics‘, 2020.

ONS (2021). ‘Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality – Office for National Statistics‘, 2021.

Radziwinowiczówna, Agniezska, and Aleksandra Galasińska. ‘“The Vile Eastern European”: Ideology of Deportability in the Brexit Media Discourse’. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 10, no. 1 (2021): 75–93.

Note: this article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.

Image credit: Rocco Dipoppa

Hi,

I have read your dissertation summery and would love to connect if possible! I am a czech designer and I have spent the last 6 years living and studying in the UK (London, Brighton, Notts). I have had quite a few interesting experiences over the years that link to your research. I often feel somewhat disconnected from my roots and alienated in British environments so I think it would be great to expand my network. Let me know if you’re interested 🙂 Thank you!