The first post-bailout national elections were held in Greece on the 7th of July 2019. Originally scheduled for the Autumn of the same year, the general elections were brought forward following the large defeat of the incumbent Syriza-government by New Democracy (ND) in the European Parliament elections held in May.

Successive opinion polls continued to show an entrenched difference between the two main parties and the victory of ND was foretold. This led to a low-key campaign revolving around two open questions: whether ND would be able to secure an outright majority and whether Syriza would minimize its losses and establish itself as the main left-wing pole of the Greek party-system. Both questions were answered in the affirmative.

The conservative ND won almost 40% of the vote, securing 158 seats in parliament. Much of the credit for the big win went to the new party leader, Kyriakos Mitsotakis. A descendant of a political dynasty, Mitsotakis successfully cast himself as a modernizer, while ND, a party founded in the 1970s, was presented as a vehicle for political renewal. ND’s pledges included measures to stimulate growth, tax cuts, and strengthening public safety and security, with special emphasis to the “forgotten” Greek middle class.

On the other side, Alexis Tsipras emphasized that the Greek economy had been catching up, while also promising tax relief, the creation of new jobs and wage increases. Syriza representatives also criticized ND for its “punitive” neoliberal economic agenda stressing Syriza’s progressive governing record.

Beyond economic issues, which dominated the campaign, foreign policy also gained some visibility. In particular, Syriza continued to be criticized for the Prespa agreement, which had settled the protracted name dispute with Greece’s neighbor, Northern Macedonia. The party’s losses in Northern Greece signal that some voters indeed turned away from Syriza because of it.

Despite the fact that Greece still hosts a large number of refugees, immigration was relatively low on the agenda, though the issue remains polarized. Left-wing parties took migrant-friendly positions, focusing on respect for human rights, a path to citizenship and social protection of migrants and refugees. Conversely, ND took relatively restrictive positions, advancing proposals to defend and strengthen Greece’s borders. Mitsotakis also visited a number of islands in the Aegean that had been the epicenter of the crisis pledging to speed up asylum procedures and sent back to Turkey those who do not qualify. That said, communication on the issue was low-key and managerial with the party-leadership refraining from brash identity-politics (despite some prominent ND members coming from the space of the far right).

The low salience of immigration may explain in part why Greece’s notorious extreme right party, the Golden Dawn (GD), practically collapsed: already in the preceding EP elections the party reached less than 5 points, and in the general elections failed to pass the 3% threshold altogether, securing zero mandates. The loss of GD was welcomed by the overwhelming majority of politicians, commentators and journalists. At the same time, a new far right populist party emerged, Greek Solution (GS), lead by former LAOS MP, Kyriakos Velopoulos. The party is less extreme than the GD, however, it ticks all the boxes of anti-establishment populism and exaggerated nationalism, including anti-immigration, xenophobia, Islamophobia, welfare chauvinism, Euroscepticism, and conspiracy theories. With the decline of GD and the virtual disappearance of the Independent Greeks (ANEL), however, overall support for the far right declined in these elections.

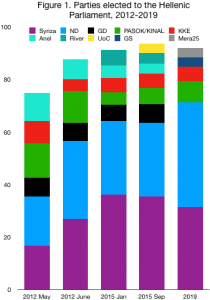

What kind of broader trends emerge? It seems that the opportunities opened up by the economic crisis have diminished. From hindsight, it is apparent that the turmoil of the party-system reached its apex with the the 2012 May elections, when volatility exploded and the system appeared extremely fragmented (see Figure 1). Since then, nonetheless, we have witnessed a gradual re-concentration and simplification, and the 2019 general elections confirm this trend.

Syriza managed to assert itself as the main left-wing pillar of the party-system while ND recovered on the right. With this, the traditional structure of bi-partism has returned, albeit in a more fragile form. The smaller parties that appeared in the crisis (ANEL, To Potami, Union of Centrists (UoC), GD) have vanished. The Communists (KKE) have stabilized at around 5% and the Movement for change (KINAL), the heir of PASOK is a stable third force. The only two new parties that managed to pass the electoral threshold are the aforementioned GS and Mera25, a progressive party founded by former minister of the economy, Yanis Varoufakis.

On the whole, the results of the 2019 general elections were widely interpreted as a return to normalcy. The transfer of power was smooth and swift, and the new cabinet formed within a day. As a way to signal his commitment to renewal Mitsotakis included in the cabinet a considerable number of extra-parliamentary members – though the low participation of women (only 5 of the total 51) derailed his effort to appear reform-minded. The government of ND had a dynamic start, announcing a few days after the election the first plans for tax cuts and administrative reform. It remains to be seen if ND will be able to implement the promised reforms, which require opening new negotiations with the country’s creditors in order to lower the required primary surpluses.

Note: This post draws on the author’s report about the 2019 Greek general elections prepared for and published by the Mercator Forum for Migration and Democracy (MIDEM).

The report is available here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.