Greece created an independent public revenue authority as a condition for receiving financial assistance during the country’s debt crisis. As Dionyssis G. Dimitrakopoulos and Argyris G. Passas explain, the reform effectively depoliticised tax collection, which had long been a major problem in Greece. They write that while it is still too early to assess whether the reform will be successful in the long-run, it represented a radical break with the past, and remains the only structural reform of Greece’s public administration that has been carried out in full since the crisis.

Poor tax collection was a key factor that brought Greece to an unprecedented crisis of its public finances more than a decade ago. It has also been one of Greece’s enduring problems since the establishment of the modern Greek state in 1830. In a new book, we analyse the main reform of its public revenue administration that was introduced under the bailout agreements concluded by successive Greek governments and the country’s international partners. These agreements were based on conditionality, i.e. the provision of vitally needed funding in exchange for domestic reforms.

This specific reform consists in a determined effort to ‘depoliticise’ Greece’s public revenue administration, i.e. to move it from being part of the Athenian central government operating under direct ministerial (i.e. political) control, to a public revenue authority that is functionally independent, administratively and financially autonomous vis-à-vis the government of the day. In other words, while in the past the government was responsible for both making and implementing tax policy, now it controls only the former, leaving the latter in the hands of an independent authority that operates at arm’s length from the government.

This reform came about as a result of external pressure from the IMF (an institution that has been championing this reform) and the EU, rather than domestic demand. While it appears to address a key factor behind the country’s poor tax collection, i.e. government interference, it raises significant issues regarding both a) the new institution’s democratic accountability and b) sustainability since it operates in a political environment that is hostile to institutions of this kind.

The depoliticisation of Greece’s public revenue administration is remarkable because it is radical, it has been implemented during an unprecedented crisis and it is the only structural reform of Greece’s public administration that has been actually carried out in full during the crisis. To understand the magnitude of and the necessity for this reform, one ought to take a look at the pre-crisis state of the country’s public revenue administration. It was in a highly problematic state characterised by the presence of corrupt, highly ineffective and ageing staff accustomed to political interference, and limited use of IT, i.e. the absence of political will of successive Greek governments to rationalise tax collection. Instead of reforming tax collection, they preferred borrowing to plug the chronic budget deficit.

How did we get there?

Moving the public revenue administration away from direct ministerial control was not immediately placed on the reform agenda that the IMF and the EU hastily put together in the early stages of the crisis. Indeed, the first bailout agreement (2010) did not even mention it. The country’s international partners were not aware of the scale of the problem of the public revenue administration’s deep-rooted politicisation, were under huge pressure to help avoid a bankruptcy and, faced with an acute crisis, reasonably opted for small, specific reforms that did not go anywhere near the root cause of the problem of constant political interference in the daily operation of the public revenue administration. Depoliticisation became a key objective under the second and – in particular – third bailout agreements (2012 and 2015 respectively). It was finally enacted in May 2016 and came into effect in January 2017 despite consistent opposition form the country’s political establishment.

Two governments of different political persuasions sacked (in 2014 and 2015) the first two heads of the public revenue administration (albeit for different reasons). At that point in time the public revenue administration had a limited degree of semi-autonomy. Even that limited semi-autonomy was due to the pressure exercised by the IMF and the EU.

There are three potential explanations. The first is external pressure which alters the calculations made by domestic political actors. The second (social learning) is based on the idea that domestic actors may be persuaded to enact reforms that are seen to be legitimate, equitable and shared internationally. The third (lesson-drawing) is couched in the search for solutions to an existing problem but, unlike the first explanation, starts from domestic pressure in favour of reform. As we explain, the latter two explanations ought to be rejected because they rely on domestic ownership of the reform. This ownership was simply not there. So, this reform came about largely because of the pressure brought about by the IMF and the EU.

What has changed?

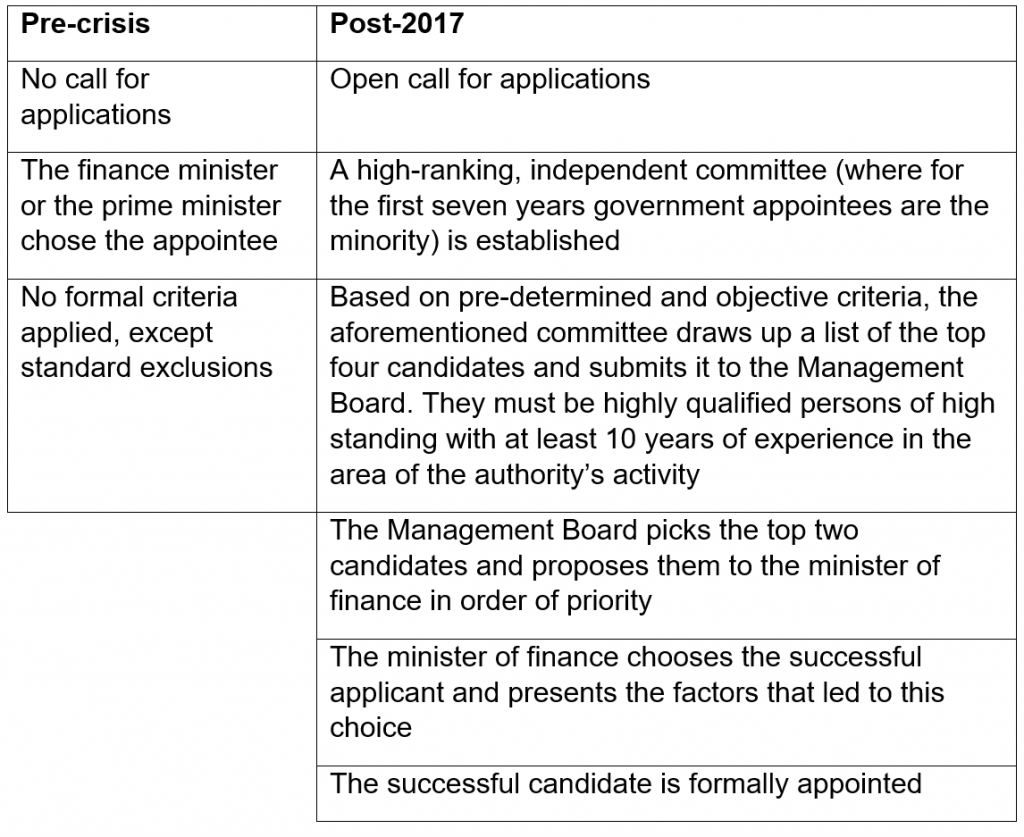

This reform has brought about two sets of changes. The first headline-like change concerns the way in which the head of Greece’s public revenue administration is chosen. This is illustrated in the following table.

Table: Changes in the selection process for the head of Greece’s public revenue administration

Source: Dimitrakopoulos and Passas (p.134)

The second set of changes relate to a) the use of modern management techniques and b) new lines of accountability. The former entail modern management tools such as risk analysis for targeting sectors, areas and individuals who are more likely to evade paying taxes, and the widespread use of IT so as to free up staff for audits. In terms of accountability, the Independent Authority for Public Revenue now reports to parliament. The hope of its creators is that the authority will thus remain accountable without being under the control of the government. The problem is that Greek parliamentarians are not used to the kind of painstaking, evidence-based work that holding this kind of specialised authority to account would entail. Rather, they prefer sloganeering.

Will it survive?

While the reform was enacted with the explicit support of the main opposition party, the real test will come either when taxpayers or a powerful group thereof complain about overzealous tax collection, or when the European Commission is no longer present in the panel that selects the head of the institution.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics. The research on which this article is based was funded by the LSE’s Hellenic Observatory. Featured image: Public Domain (CC0 1.0). This article was originally published on the EUROPP – European Politics and Policy Blog.