In a time of change and uncertainty, four academic developers from different disciplines, Jenni Carr, Natasha Taylor, Catriona Cunningham, and Jennie Mills, revisit Haynes’ and Macleod-Johnstone’s powerful paper Stepping through the daylight gate: compassionate spaces for learning in higher education and aim to make connections with how compassion plays an integral role in their practice

The stories did not lie intact and waiting within us, they emerged within the space of the group, the breathing bodies that also constituted the space: the gazes, the pauses, the tensions.

The stories referred to above are responses to a question posed by the researchers leading the Dangerous Knowledge project: has your work as an academic ever felt dangerous, difficult or disturbing? The themes that emerge from the stories told form part of the ‘landscapes of liminality’ identified and discussed in the article. Whilst I had originally downloaded the paper as part of a library search for work relating to kindness, emotions and compassion in higher education, it was the focus on spaces and, in particular, the liminal nature of some spaces, that sparked my interest.

Part of the academic developer’s role in many institutions is to observe and provide feedback on our colleagues’ teaching. Occasionally requests for observations come from colleagues who would like advice on a particular aspect of their practice – as academic developers we are ‘invited in’. More often than not, however, the observations are a required part of studying for a qualification or part of a framework for accreditation – we invite ourselves in!

All the academic developers I know view the process of the teaching observation – not just the observation itself, but the feedback conversation that follows – as an opportunity for peers to exchange practice. It is perfectly understandable, however, if not all our colleagues are quite so positive about the prospect of having someone observe their teaching.

Land discusses the resistances there may be to academic development practices. He highlights the relatively private nature of teachers’ interactions with students, and how within the managerialist discourses that so often dominate in higher education, academic developers might be viewed as “intruding to render visible, and hence calculable, previously private practices.”

Through discussions with fellow academic developers I know that there is fierce resistance to the idea that we become complicit in “the production of the ‘malleable-but-disciplined’ individual that is so necessary to enterprising culture.” But how can we practice that resistance in a way that both meets the needs of teachers, but also subverts the excesses of a managerialist approach to education?

John Clarke argues that whilst stories of power “squeeze – in material and symbolic ways – the spaces that we inhabit” we should not lose sight of our capacity to “create breathing and thinking space: to lift the pressure, to find the ‘leaky’ parts of the system and the weak points of its embrace.”

I would argue that, in this context, those breathing and thinking spaces should be characterised by compassion. It is important, of course, that we provide colleagues with advice and resources to develop their teaching. The spaces created as part of teaching observations, and the conversations that take part within them, do not, however, have to be solely instrumental in nature. We can also create spaces and conversations “to care for, care about and to take care of” any colleagues whose experiences of teaching have ever felt, as Haynes and Macleod put it, dangerous, difficult or disturbing.

Jenni Carr

Don’t think that I don’t know that this assignment scares the hell out of you, you mole!

Picture me reading this article for the first time. Sunken shoulders, sighing. All the things I find really difficult – emotions, poetry, liminality. This is not my comfort zone. I immediately think of the character, Todd Anderson in the film above, facing the horror of a poetry writing assignment, fearful that his vulnerabilities will be revealed and exposed.

But, as I re-read the piece, it struck me that vulnerability is one of the strongest catalysts and currencies in the work I do. Whether I am delivering teaching workshops or supporting reward and recognition activities, I ask people to make themselves vulnerable – either through analysing their failures or by ‘showing off’ their achievements in a competitive process. I help them to construct, interpret, and share their narratives and re-frame them as learning. This can – as the article confirms – be challenging. I have to make myself vulnerable.

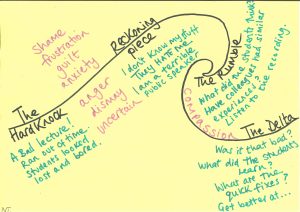

The authors call for more ways to explore negative affect so that it becomes educative, acknowledging that this is tough in a heavily performative university culture. But how? I discussed my initial thoughts with a friend; she quickly related the work of Brené Brown – a University of Houston professor with an impressive research portfolio on courage, vulnerability, shame and empathy. In Rising Strong, Brown presents what she calls a ‘hopeful path for learning’ and I soon discovered that this could be a useful framework to build opportunities for learning from difficult, disturbing and dangerous episodes. In a nutshell, the Rising Strong process is:

1. A hard knock

Experience a failure, a criticism, a rejection or a betrayal.

2. The reckoning piece

Accept that you have been ‘smacked by emotion’ and allow yourself to ‘get curious’ about what is happening.

3. The rumble

Compose your own story to explain a situation (Brown calls it the ‘shitty first draft’). Once complete, you can reality/fact-check it with others.

4. The delta

Hold up the ‘shitty first draft’ alongside the alternative versions and learn from it.

I sketched out what this might look like in the higher education context (I chose wave over juggernaut!). It is typical of the conversations I have every day and includes the things we tell/ask ourselves (green) and the emotions that come into play (pink).

I do believe that Brown gives us an evidence-based process that puts danger and emotion at the heart of reflective practice and experiential learning. It is so rich that it can be translated into practical ideas for supporting our work – for example, encouraging the use of teaching journals and creating safe spaces for conversations (rumbles) to take place. Compassion is both, the concrete in the framework and the undercurrent which drives the tides of vulnerability.

So, back to Todd Anderson. He faces his fears, steps through the daylight gate, voices his poem. Academic development can be an overwhelming experience – we dance with vulnerability, daily. I realise that I have had to learn the art of compassion and to let emotion play a role in my own sensemaking. It still scares the hell out of me; I hope it always will.

Natasha Taylor

All their doors remained simple doors, on/off switches in the flow between two adjacent places, binarily either open or closed, but each of their doors, regarded thus with a twinge of irrational possibility, became partially animate as well, an object with a subtle power to mock, to mock the desires of those who desired to go far away, whispering silently from its door frame that such dreams were the dreams of fools.

Exit West, Mohsin Hamid

Haynes and Macleod-Johnstone create an in-between space that enables those present to share moments of intimacy from their classrooms that may evoke pain, shame, laughter and myriad emotions that encompass the messy and complex practice that is teaching. They also highlight the challenge of working in higher education confronted by the ‘juggernaut of incessant change’ which is felt here as brutality or even violence. Above all, the article is a powerful reminder of the importance of agency in a landscape where the individual feels barricaded into a system from which there is no way out. The authors, therefore, create a delineated space where they and their colleagues are free to explore their academic practices.

The significance of a closed space, which is lived as sacrosanct by the authors where they could ‘step through the gate’ resonated with me, but it also made me think that the gentleness of such threshold-crossing was not at all my experience of academia, nor for those of my colleagues. In fact, I remembered the powerful magical realist novel by Mohsin Hamid where the characters open doors to find themselves suddenly thrust into entirely new countries with no border crossing at all. In this context, arrivals and departures in new worlds are brutal with no transition, no easing into new languages and cultures. Instead, immediate adaptation is the only way in. To me, this sudden change image is more suited to our academic worlds: researchers are suddenly flown into new teaching contexts with only their strong research credentials to help them navigate this new world; or they are western ‘flying faculty’ landing in satellite campuses across the world; or they sit expectantly at their desks in front of their computers buffeted into a virtual world where they can only peer unblinkingly into the online classroom where their learners exist in a synchronous classroom. The opening and closing of the doors of the world of the contemporary western academic is a hurling, burling frenzy and this makes the intimate and open space, described in this article, a place of hope.

For there is hope for those ‘dreams of fools’ – the immediacy of the door pushing us through is forcing us to exchange worldviews and to encounter the other across and between spaces that are often filled with friction, but which then open up other doors. Indeed, as our academic practices are ushered more and more into the public domain and the harsh glare of metrics and accountability from university managers, the academy is creating new spaces and windows where we follow creative methodologies to seek plural and intercultural responses that help us to evade the juggernaut.

Catriona Cunningham

If we ask academics to hold students in a space of vulnerability and uncertainty in which they can embrace their own beings, it is necessary that we create the kind of environment where academics can explore their own vulnerability and uncertainty.

The Slow Professor, Berg and Seeber

Ostensibly Haynes’ and Macleod-Johnstone’s article is about knowledge, about a sort of knowledge which comes from slowing down, stepping away, and attending to the negative affect of academic life – anger, shame, guilt, dismay, uncertainty, vulnerability, fear. This knowledge is held secretly, harboured by those who have experienced ‘the darkness of higher education’. It waits, and is then coaxed, carefully, ethically, into the world to become ‘data.’ Two discourses are deftly woven, warped with academic discourse but shot through with stories, wefts of Atwood, “[W]e understand more than we know’ and Winterson ‘[S]oon it would be dusk’. Curiously, the stories casually shared in in-between spaces – “lifts, corridors, staircases, landings, areas next to photocopiers and kettles” – by unnameable narrators ‘[T]here were 3 or 4 of her friends in the kitchen’ are palmed. This absence seems to ‘make felt the unknowability within the unknown’.

It is also then, about the impossibility of knowledge. It embodies methodological vulnerability, a methodology which produces unknowable data, the sort of data which resists analysis and so dogmatically refuses to become knowledge, perhaps showing us the value of this work. Analysis must always already be ‘unfinished’.

Barbara Grant’s postcritical ethnographic work on doctoral supervision shares a similar approach, a small handpicked community of fellow female academics, where all are both researchers and researched. Grant articulates an understanding of ‘reality [as] constructed in contexts of power relations and that claims to final signifieds in theory or research are instead claims to power.’ Adopting Donna Haraway’s position of ‘modest witness’ her work is characterised by curiosity without judgment, ‘rigorously committed to testing and attesting’ where engagement is always ‘interpretative, engaged, contingent, fallible.’ The position of the ‘modest witness’ transfigures subjectivity into objectivity, ensuring that narratives are possessed of a ‘magical power – they lose all trace of their history as stories, as products of partisan projects, as contestable representations, or as constructed documents in their potent capacity to define the facts. The narratives become clear mirrors, fully magical mirrors, without once appealing to the transcendental or the magical.’

In this collective endeavour each researcher is their own ‘modest witness’ slowing, testing, paying attention to their own experience, exploring the ways in which they assemble themselves as academics and educators through their stories. “As Judith Butler reminds us, any accounts always being in media res, when many things have already taken place to make me and my storyin language possible. [. . . ] I am always recuperating, reconstructing, even as I produce myself differently in the act of telling. My account of myself is partial, haunted by that for which I have no definitive story.’ Our stories are always imperfect, incomplete, multiple, evolving, contingent, contradictory, elusive. Our stories masquerade as authentic lived experience, so analysing these ephemeral representations tells us little of ‘truth’. Instead value lies in the collective process of assembling, telling, reading and re-reading, of dwelling in the darkness, exploring our own vulnerability and uncertainty. Our role as academic developers should be to hold time and space, dim the lights, and dwell with our colleagues in the darkness.

Jennie Mills

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*Image information

Image of door and lock: https://www.publicdomainpictures.net/en/view-image.php?image=297918&picture=door-handle-in-brass

Thank you to all the authors for such a thought-provoking, wonderful and enriching read.

Thank-you for taking the time to read it Sebastian, and we’re glad you enjoyed it!