Although the narrative of student volunteering is largely positive, there are barriers that inhibit some students from reaping these benefits. Arya Gerard draws on her experience and research to delve into how the increasing association of volunteering with CV-building and employability runs the risk of morphing student volunteering into a competitive battlefield that could disadvantage some students.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a Christmas favourite in our home: the storyline of generous and good-willed Charlie Bucket finding a golden ticket, eventually earning the right to run the Willy Wonka empire, wins over our hearts every time we watch it. As Christmas nears yet again, it has got me wondering if the Charlie Buckets of our world really do get the ‘golden tickets’ or if the Veruca Salts get to them first.

Some of us might recall giggling at Veruca Salt’s fall down the trap door after being deemed a ‘bad egg’ in the 1971 Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory film; Veruca arguably embodies the antithesis of a volunteer as an innately self-interested individual. However, such a statement presumes that volunteers are predominantly driven by altruistic motivations. Notably, research has indicated that volunteers are in fact driven by an indistinguishable combination of altruistic and self-interested factors. The LSE Volunteer Centre’s 2019 survey found that 86.8% of respondents who considered volunteering were motivated to give back to society, whilst a smaller proportion of 61% were motivated to develop their CVs (curriculum vitae). Whilst it may be that most students have mixed motivations to volunteer, some volunteer because it is a norm within their social sphere.

Enhancing employability, promoting overall wellbeing, developing valuable skills and the ability to make a positive impact are some of the advantages volunteering is perceived to equip students with. Seeking to make sense of this labyrinth of volunteer motivations might explain why someone like Veruca Salt or Charlie Bucket end up volunteering for the same cause, but it does not address the bigger question: is Veruca Salt better placed than Charlie Bucket to consider and secure volunteering opportunities? As Ryan Lim, a recent LLB graduate from LSE notes, “Applying for some volunteering opportunities can generally be quite competitive and intimidating. This means people who are willing and able to help are deterred by the requirements of supplying cover letters and CVs”. It appears that student volunteering is turning into a battlefield with some better placed than others to secure volunteering opportunities.

student volunteering is turning into a battlefield with some better placed than others to secure volunteering opportunities

Barriers to student volunteering

One’s personal resources such as time, money, and skills impact their involvement with volunteering. Scarcity of time as a result of studying is a significant deterrent amongst LSE students with 86.3% of respondents to this year’s Volunteer Centre survey expressing that it has put them off from volunteering whilst at LSE. Although the Volunteer Centre has actively tried to circumvent time constraints by promoting micro-volunteering and one-off volunteering opportunities, institutional and socioeconomic barriers beyond personal scheduling persist.

Securing volunteering positions at external organisations often requires students to complete application forms. These forms usually require students to demonstrate relevant existing skills whilst supplying a minimum of two referees. Despite the Volunteer Centre’s provision of one-to-one support in completing such applications, students might be put off by the bureaucratic process or time-consuming nature of submitting applications. Moreover, these procedural barriers might further inhibit students who are new to volunteering and don’t have an extensive skillset. Students with disabilities are also at greater risk of being excluded from volunteering as they are more likely to be unable to demonstrate relevant skills and qualifications.

Notably, the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) ’s Volunteer Experience Survey identified that individuals from higher socioeconomic groups were more likely to volunteer than those from lower socio-economic groups. A final-year undergraduate from LSE’s Economics department expressed that she feels more inclined to choose paid opportunities as they enable her to support herself financially. “Making time for volunteering is not an option for me. It doesn’t help with paying the rent and I’m already knackered from balancing school with work”. Hence, statistically it seems that students with a socioeconomic background similar to Charlie Bucket are positioned such that they are less likely to consider volunteering. Perhaps the concern of equal opportunities pertaining student volunteering would not arise if it were to be integrated into students’ core curriculum.

Making time for volunteering is not an option for me. It doesn’t help with paying the rent and I’m already knackered from balancing school with work

Integrating volunteering into core curriculum: have we got it right?

The integration of volunteering into the core curriculum is commonplace amongst higher education institutions in the UK and it could be argued that institutions have an onus to transform students’ volunteering experiences into meaningful learning experiences. Vicky Adeturinmo, LLB graduate from the University of Birmingham who currently volunteers with Citizens Advice expressed that she would have liked for volunteering to have been integrated into her main curriculum. “I volunteered with the Law School’s Pro bono group as I was personally interested in getting involved even though it was not mandatory. Integrating volunteering into our curriculum could provide the necessary support to continue volunteering in the future and help with our personal development”.

However, it seems that volunteering is increasingly subsumed by CV enhancement when integrated into one’s core curriculum. For instance, Newcastle University offers a career development module incorporating a minimum 70 hours of volunteering that second-, final-year, and Masters students can partake in, whilst Edinburgh Napier University offers a Volunteering and Employability module requiring students to complete a minimum of 20 hours of volunteering. Although these examples of integrating volunteering into curriculum are beneficial for students, it runs the risk of alienating the multitude of benefits volunteering provides by focusing on CV enhancement and employability. As Holdsworth indicates, “We need to recognise that volunteering will lose many of its positive attributes, that it can be fun and scary; it can take students outside their comfort zones, to meet new people and experience challenging situations. These contingent qualities of volunteering are too valuable to be lost at the expense of emphasising skills and employability alone.”

Integrating volunteering as an element of credit-bearing modules mitigates the initial barriers that potentially morph volunteering into an unfair battlefield for some students. Yet, it fails to espouse the benefits of volunteering in its entirety. Some higher education institutions have sought an alternative remedy.

These contingent qualities of volunteering are too valuable to be lost at the expense of emphasising skills and employability alone

Mandatory volunteering: is community service the solution?

Enforcing compulsory volunteering might seem like a paradox as volunteering is premised on one’s discretion. Ryan feels that making such activities mandatory tempers with the essence of volunteering. “Volunteering should be contingent on conscious choice. Compulsory volunteering would minimise the satisfaction one gains from volunteering.”

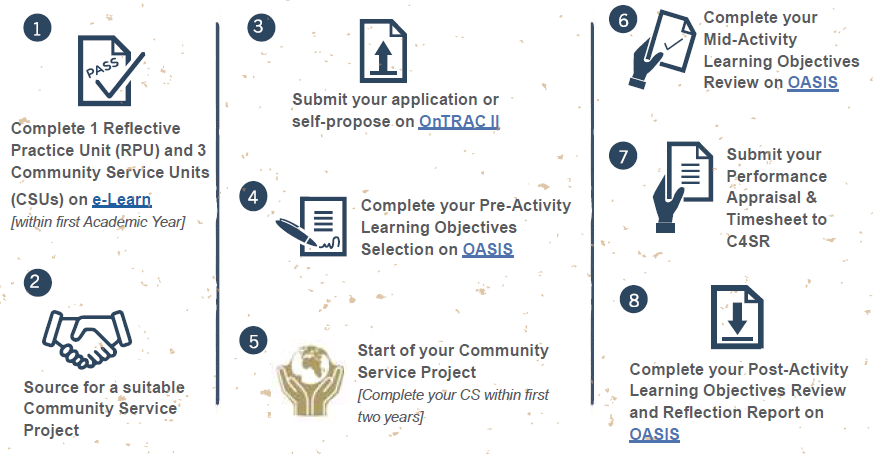

Yet, the notion of embedding mandatory volunteering as community service within the curriculum is the norm in some universities. Since 2013, the Singapore Institute of Legal Education has made it compulsory for law undergraduates to meet a minimum number of 20 pro bono hours to successfully graduate from university. Singapore Management University (SMU) requires all of its students, regardless of their discipline, to complete a mandatory non-credit bearing 80 hours of community service over their four years of undergraduate study. On average, each student that graduated last year contributed 135 hours of community service, exceeding the minimum requirement. Markedly SMU’s transformative education policy requires community service to be integrated through credit-bearing programmes in the curriculum beginning this academic year; law undergraduates are still required to volunteer on a non-credit-bearing basis.

Singapore Management University issues a checklist and timeline for students to keep on top of their mandatory community service requirements*

Singapore Management University issues a checklist and timeline for students to keep on top of their mandatory community service requirements*

Claire Lim, an LLB graduate from SMU, feels that the incorporation of community service has been beneficial overall. “I think volunteering helps to inculcate important values such as being giving and thankful. I took up more diverse volunteering opportunities than I would have if it were not part of my curriculum; I spent four weeks in Laos building schools and 20 hours volunteering at local pro bono legal clinics.” Conversely, a recent graduate from SMU’s Law department highlights that imposing community service could be a barrier for students. “Some might find volunteering disruptive to their schedule and it may add stress, making it a less desirable activity. I completed the minimum volunteering threshold in two years instead of four as it was just another box to tick. However, I do believe the compulsory 20 hours of pro bono volunteering was beneficial to my understanding of the relationship between law and society.” A recent study conducted on Hong Kong’s public university students found that compulsory credit-bearing ‘service learning’ significantly benefitted students regardless of their prior inclination to get involved with it.

Community service that has been integrated into the core curriculum acknowledges and celebrates other means of learning and skill development outside the classroom setting; it is advantageous as it does not pigeonhole volunteering as a CV enhancer. Yet, compelling students to volunteer disregards the precept of choice that volunteering is premised on. Further, compulsory volunteering, even when incorporated as a form of community service, exerts a layer of control that could inhibit students from considering volunteering in the future.

Veruca Salt and Charlie Bucket*

Veruca Salt and Charlie Bucket*

Helping Charlie and Veruca?

Volunteering incorporated as compulsory community service ensures accessibility; this would benefit students like Charlie. It also focuses on benefits beyond employability and CV enhancement; this would benefit students like Veruca who prioritise the personal gains derived from volunteering. However, compulsory community service poses as an obligatory hurdle which threatens the desirability and essence of volunteering.

This does not mean that universities should adopt a hands-off approach towards student volunteering; universities should continue to play an active role in the volunteering arena as students receiving support from their universities report better experiences volunteering overall than those students who volunteered directly with external organisations.

Instead, incorporating volunteering into the core curriculum without marketing it solely as a CV or employability enhancer is better able to maintain the integrity of volunteering and ensure students retain their capacity to choose. Hence, the issue is not with incorporating volunteering into core curriculum, but rather the way in which it is being incorporated.

We should not attempt to dictate the extent of volunteering students should engage in, since the Charlies are inevitably disadvantaged; nor should we seek to artificially alter the Verucas’ motivations to volunteer simply because we presume they are predominantly egoistic. Rather, we should seek to enable both Veruca and Charlie to volunteer by providing effective support and ensuring accessibility to volunteer for all students; the ability to volunteer should not be contingent on possessing a golden ticket.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Main image: https://wonka.fandom.com/wiki/Veruca_Salt https://www.her.ie/entertainment/remember-the-original-charlie-bucket-heres-what-he-looks-like-now-257523

SMU Checklist image: https://www.smu.edu.sg/campus-life/community-service/community-service-guidelines

This will be the last post on the LSE Higher Education Blog this year. We will close for the Christmas holidays and will resume blogging in January 2020. We wish our readers, contributors, and collaborators a restful break.

I like this blog, I will come back to see the next post

I like this blog, I will come back to see the next post

tq

Very Good Article. Thanks