Philip Belau is a current MSc Human Rights student at LSE and president of the Human Rights Student Committee 2014/15. He holds a bachelor’s degree in History and Politics and has been involved in several humanitarian projects in the Middle East. He is currently working as the executive director of a grassroots organisation for Syrian refugees.

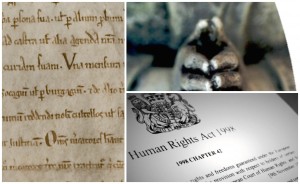

It is bleakly ironic that as we mark the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta Libertatum, the United Kingdom is facing a new law that seems to squash some of the most fundamental civil liberties of democratic society. While the occasion should be a reason to celebrate what has evolved from a local agreement to a powerful international symbol of our liberties, the recently passed Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 (CTSA) casts a long shadow over the event.

It is bleakly ironic that as we mark the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta Libertatum, the United Kingdom is facing a new law that seems to squash some of the most fundamental civil liberties of democratic society. While the occasion should be a reason to celebrate what has evolved from a local agreement to a powerful international symbol of our liberties, the recently passed Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 (CTSA) casts a long shadow over the event.

The new legislation, which became law earlier this year, marks the latest in a long line of counter-terrorism measures that have been adopted in the UK as part of the ‘global war on terror’ since 9/11. Starting with the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act of November 2001, the British government has introduced several pieces of legislation to facilitate its counter-terrorism response. These laws not only expand the powers of the British government but also challenge the philosophical and political integrity of the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), leading to the erosion of human rights standards in the UK.

The UK House of Lords ruled in the 2007 case of Huang that where a public authority interferes with a qualified right under the HRA, without prior derogation, it must justify that interference by demonstrating it is legal and proportionate. This judgment gave rise to a four-step test – now known as the “Huang test” – to determine proportionality. This “Huang test” requires any law interfering with a qualified right to have: (1) a legitimate objective; (2) a rational connection to that objective; (3) the minimal possible impairment to rights; and (4) an overall balance between the impact on rights and its objective. Today this doctrine of proportionality is one of the most important principles used by UK courts to review a law’s impact on rights under the HRA, and ensure that “a sledgehammer [is] not used to crack a nut”.

The CTSA was introduced as a legal response to the threat of Islamic State (IS) and the power vacuum in the IS-controlled region in Syria and Iraq. More specifically, it was meant to respond to the foreign recruitment of fighters from the UK and to disrupt their return in order to prevent attacks in the country. The provisions of the CTSA can be split in two distinct areas: ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ responses. While the ‘hard’ responses aim at arresting ‘terrorists’, the ‘soft’ responses aim to tackle and prevent extremism. The provisions at part five of the CTSA titled “Preventing people being drawn into terrorism” fall under the ‘soft‘ responses, and are a part of the Government’s so-called Prevent strategy. These preventative provisions of the CTSA oblige specified authorities “to have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism” and to report “vulnerable people” who are at risk of becoming involved in terrorist related activity. Specified authorities include schools and universities, along with nurseries and childcare centres.

The possible impact of these measures on freedom of speech has raised widespread concern, especially in higher education institutions. While the provisions explicitly state that the implementing body – for instance a school or university – “must have particular regard to the duty to ensure the freedom of speech” as well as to the “importance of academic freedom” the obligations raise several practical questions. In addition, the ill-defined terminology of “vulnerable” people seems to leave room for interpretation that promises to have a significant chilling effect.

As well as the freedom of speech concerns, the preventative provisions of the CTSA potentially infringe at least two European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) Articles incorporated into UK law through the HRA: freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 9) and the freedom of expression (Article 10). Whether the potential interference with these two rights is proportionate and thus allowable under British law can be evaluated with the Huang test. Firstly, as to whether the law has a legitimate objective, the answer is a tentative ‘yes’. The London bombings of 2005, the Glasgow airport attack of 2007 and the murder of Lee Rygby in Woolwich in 2013 indicate that terrorist attacks in the UK are a real threat. In light of the military success of IS in the Middle East, this threat is as high as ever – a factor that led the UK’s Independent Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre to raise the national threat level from “substantial” to “severe” in August 2014, where it remains. Furthermore, the British Government estimates that approximately 1600 citizens have already left the UK to fight for IS in Syria and Iraq, and this number will likely grow as the conflict continues. Addressing the radicalisation of these people is arguably a sufficiently important objective to justify the interference with the rights under Article 9 and 10 of the ECHR.

As to whether there is a rational connection between the law and this objective, the UK Government has argued they have a “fundamental duty” to take measures to safeguard citizens from terrorist attacks. Given the estimated number of radicalised individuals, it is reasonable for the British government to take legal measures to address radicalisation, especially among young people. Preventing people from radicalisation seems therefore to have a rational connection to the objective of preventing terrorist attacks in the UK.

The next step in the proportionality test is to determine whether the proposed measures have the minimal possible impairment on the particular right. As the provisions have not yet been subject to judicial review, it is difficult to predict how the Courts will rule on this point. However it is highly questionable whether the provisions are no more than what is necessary to accomplish the stated objective. The likely further stigmatisation of Muslims, a group that comprises around five per cent of Britain’s overall population, is almost certain to impose more than ‘minimal impairment’. In addition, it should not be the duty of the staff of schools, universities, nurseries and childcare centres to monitor for extremism. If untrained authorities are to identify people vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism, these orders will certainly have a significant chilling effect when exercised. Given this accumulation of factors, the preventative provisions of the CTSA clearly fail the requirement of minimal impairment under the Huang test.

Finally, with regard to the overall balance, it can be argued that the preventative provisions propose unnecessary and disproportionate restrictions on civil liberties. Crucially, the preventative provisions are subject to vague and broad standards of evidence and insufficient due process safeguards. Instead of an independent judicial hearing, the provisions will be overseen by a panel of persons consisting of the responsible local authority, the chief officer of police and two other persons selected upon agreement of the two former. To empower such a panel with the task of assessing an individual’s vulnerability to radicalisation risks undermining the rule of law. Additionally, the provisions seem to reverse the fundamental legal maxim of ‘innocent until proven guilty’, shifting the burden of proof of innocence onto the accused. It may be that in practice these powers are exercised carefully, but the loose way the document is drafted leaves a high risk for abuse.

As already noted, the implementation of the new counter-terrorism law will likely affect a vast number of people in the Muslim community in particular. To antagonise and marginalise a substantial part of the British population is not only to be counterproductive but dangerous, as it deliberately generates and inflames an atmosphere of ethnic and religious profiling. This process of marginalisation could exacerbate the current alienation of Muslims in Britain. Given the different impacts mentioned above, the preventative measures do not strike a fair balance between the rights of the individual and the interests of the community.

In light of the likely impacts of Britain’s new counter-terrorism law, one has to ask whether it is necessary to curtail civil liberties in order to respond to terrorism. The assertion that the enjoyment of these rights is exclusively dependant on a ‘secure environment’ provided by the state leads to illusory security demands no government is able to fulfil. Instead, national security and civil liberties should not be understood as inherently incompatible. They have to be seen as complementary and mutually reinforcing one another and thus cannot simply be ‘balanced’ against each other.

Bearing all of this in mind, the doctrine of proportionality does not present a convincing approach when developing legal measures to counter international terrorism. Instead, effective counter-terrorism strategy is best met not by enacting more restrictive policies, but by supporting and strengthening political and social dialogue within society itself. To put it in the words of Richard Criley, “our individual rights depends upon their availability to everyone, including some people whose beliefs we may not like. But if the rights of any unpopular group or minority are weakened by a decision [of the government], we will all lose some of our individual freedom in the process”. It is without question that the wrong measures promise inefficiency in the fight against international terrorism, but to quote the German poet Hans Enzensberger: “to shoot sparrows with cannons: that would mean to make the reverse mistake”.