Laura Vidal is a social worker with a masters degree in human rights law and policy. She is currently employed by The Salvation Army Australia’s Freedom Partnership to End Modern Slavery.

Click here for all blog posts in this series

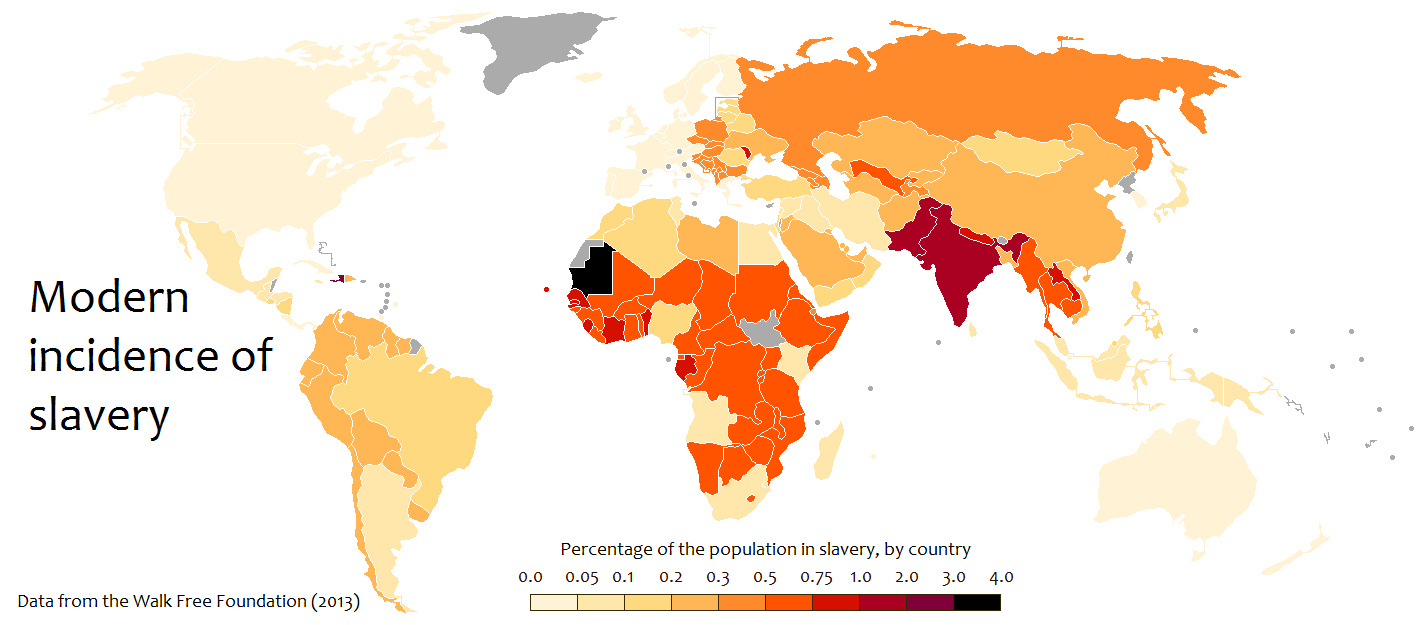

The Global Slavery Index estimates that over 35 million people are enslaved today. Far from a remote problem, we are all connected to people in slavery through the clothes we wear, the food on our dinner table and many of the other products and services we consume. People all over the world have their labor exploited for the benefit of distant others. For this reason, including the eradication of modern slavery in the Sustainable Development Goals (S.D.G.s) is essential to its achievement worldwide because it raises modern slavery to the purview of globally-connected actors.

Following the Millennium Development Goals, established in 2000 to halve poverty by 2015, the objective of the S.D.G.s is to eradicate extreme poverty worldwide by 2030. In order to achieve this, 17 specific targets have been agreed upon by participating U.N. member states – goals ranging from protecting the environment and ensuring sustainable ecosystems, to reducing inequality and promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth through dignified employment opportunities and conditions.

While United Nations mechanisms are often criticized for not having enough teeth, the adoption of S.D.G.s – formally announced in August 2015 – points to a far-reaching alignment of national and non-governmental agendas to combat the multivalent roots of poverty and social vulnerability. Agreeing upon transnational goals is important pragmatically and ideologically. Owen Gaffney of the Stockholm Resilience Centre writes, “Setting goals works—in a complex world, organisations and countries can align their agendas and prioritise funding.” Without such cooperation, measures to combat poverty become cellular and may be diluted by national interests. According to a report by the U.K.-based Overseas Development Institute the S.D.G.s “represent the closest humanity has come to agreeing [on] a common agenda for a truly inclusive future where no one is left behind.” This is particularly relevant because, for the first time, the eradication of modern slavery has been articulated as a problem facing all of humanity.

Modern Slavery as a Development Issue

Including modern slavery in the S.D.G.s means addressing the underlying factors that contribute to the vulnerability that place people at risk of enslavement. According to Adrian McQuade, director of Anti-Slavery International, vulnerability predominantly includes “material poverty, but it can take other forms such as vulnerability to threat of physical violence or, increasingly, being forced to migrate.” Coupling these with the systemic discrimination faced by low-wage workers results in large groups of people in danger of exploitation and enslavement.

The anti-slavery target in the S.D.G.s falls under the goal to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.” Given that poverty is a leading cause of vulnerability, addressing modern slavery in the context of development makes sense. More than that, the anti-slavery goal identifies broad discrimination in employment as a fundamental cause of human disempowerment. This, in turn, signals that a robust strategy for labor rights is essential.

From Prosecution to Prevention

The inclusion of modern slavery in the S.D.G.s indicates that addressing modern slavery has been moved out of the isolated realm of criminal justice. Such approaches focus on the need to prosecute and punish violent criminals who physically exploit the labor of individuals. Whilst it is important to continue to hold accountable those who unscrupulously exploit other people for personal gain, we cannot be truly serious about eradicating modern slavery if we view it solely as the result of deliberate criminal activity engaged in at the personal level. The S.D.G.s compel us to view slavery as a complex economic and social system, globally sustained and perpetuated by a complex range of actors. They acknowledge that modern slavery is not an isolated phenomenon and elevates responsibility for its myriad forms to the level of the global community.

In light of this, it is difficult to accept that the inclusion of its eradication in the development agenda has taken this long. Nick Jackson of Corporate Citizenship, a corporate responsibility consultancy group, writes that the inclusion of this target is “an indicative move away from aid towards trade, growth, jobs and the self-sufficiency and dignity of individuals, communities and nations.” This points to a growing acknowledgement that modern slavery is part of a constellation of problems associated with economic vulnerability. Slavery is often the result of job instability that stems from entrenched gender and racial oppression, and international economic systems that have exploitative effects. The U.K.’s anti-slavery commissioner said that “it impedes health, economic growth, and rule of law, women’s empowerment and lifetime prospects for youth. It results in a huge loss of remittances to developing countries.”

At the national level, slavery is a significant barrier to the well-being and economic prosperity of populations at large. Victims of modern slavery experience restrictions in access to education, freedom of movement and the loss of a sustainable income. In terms of human trafficking, the inclusion of modern slavery in the global development agenda requires source and destination countries to create opportunities for individuals and communities so that they are no longer vulnerable to slavery as a means to survive in a globalized economy.

According to the U.S. State Department, the international framework for addressing human trafficking and slavery includes a “3P” approach: Prevention, Protection and Prosecution. While criminal justice approaches have tended to focus on prosecution, the inclusion of ameliorating modern slavery as part of the S.D.G.s fits unequivocally with the ‘Prevention’ aspect of this model. The S.D.G.s motivate governments and organisations to consider slavery prevention with new energy and direction. It draws us away from a highly concentrated investigation-and-prosecution model and calls for a greater responsibility on governments to invest in disrupting the economic conditions that create a fertile environment for slavery.

To end modern slavery worldwide we have to be truly serious about investing in humanity – in the life of every individual to ensure that they have the means to build sustainable livelihoods and prosperous communities. This means that inclusive employment objectives and strong social protections must be incorporated into U.N. objectives and other international cooperation efforts. This is why the acknowledgement of modern slavery as part of the global development agenda is so encouraging. We are widening the scope of activity, reaching a greater number of organizations and initiatives, and uniting as a global community. Together, if we holistically address the complexities that surround modern slavery, we have a shot at ending it.