Paper Digest is a new research tool that uses artificial intelligence to produce summaries of research papers. In this post David Beer tests out this tool on his own research and reflects on what the increasing penetration of AI into cognition and research tells us about the current state of academic research.

When you arrive at Paper Digest you are welcomed with a stark message: ‘Artificial Intelligence summarizes academic articles for you’. Conjuring a vision of automated thinking and a world in which technology does the heavy lifting for us. These types of messages are everywhere, folded into the projected promises of what AI might yet achieve. In this case, the AI is said to cut away the unnecessary bits of a research article in order to make research faster and more efficient.

Paper Digest, created by researchers at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, follows this opening message with the suggestion of the possibilities of acceleration. Its AI feature has the impact of, we are informed, ‘Reducing reading time to 3 minutes!’. This ‘solution’, as it is referred, allows the user to ‘quickly grasp the core ideas of a paper’. Leaving us to wonder what place reflection and non-core ideas might still have in the research process or learning. The development of Paper Digest, which feels almost inevitable (we could have imagined it coming), is targeted at students, researchers and ‘science communicators’. With this targeted audience, it is an example of how AI technologies are stretching further into cognition and knowledge. Innovations of this type have the potential to transform what is known and the form taken by research, teaching and learning – not least because it is part of a wider cross-current of thought, which is pushing researchers and learners in a particular direction.

I argued in The Data Gaze that the data analytics industry seeks to perpetuate and promote visions of cultural speed-up in order to suggest that data analytics are the only way that organisations can keep-up. Something similar is going on here. The implied and tacit message is; that if you don’t use AI, you will be a slow researcher, who is likely to have limited knowledge and be left behind. If there is a ‘solution’, then this implies that there is a problem. Paper Digest tells us that the ‘problem’ they are solving is as follows:

‘Today we face an exponential growth of academic literature. The number of journal articles doubles every 9 years; 3.5 million papers are published in 2017 alone…Much of published research has limited readership…Simply, the time researchers can spend on their reading is too limited – an average US faculty reads only 20.66 papers per month, spending 32 minutes each…A solution to understand more contents in less time is very much needed.’

The problem then, is that the human researcher is not in a position to keep up with the expansion of knowledge. This may be the case, but do we need to comprehend all of this proliferating content to make a contribution? The suggestion is that the piling up of research requires us to find ways to keep up and accelerate. It suggests to us that we need to be ever more efficient at dealing with these fields of knowledge, so that we can race through the materials that surround us. Of course, this would also exacerbate the problem, by pushing all of us to also produce more on a tighter timescale, ultimately adding to this avalanche of information. And so, AI is presented as a prosthetic to our limited cognition and a solution to our apparent slowness of comprehension. The growth of literature is undeniable: how we choose to react to that growth is contentious.

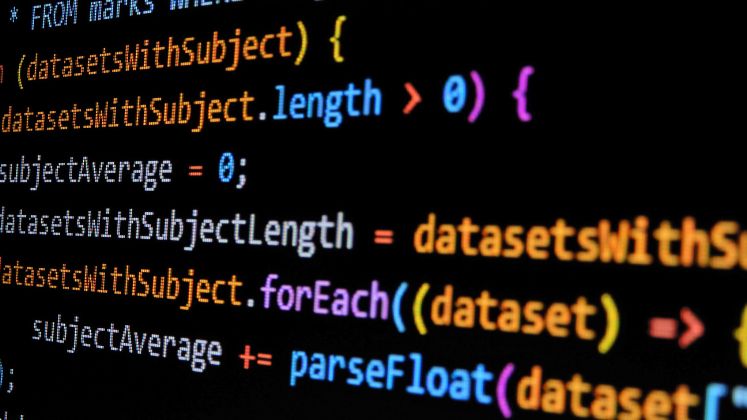

The tool itself is easy to use and you can try out the beta version for free. You just insert a link to the desired (open access) article. I tested an article of my own: The Social Power of Algorithms, which seemed a fitting choice given what I was doing.

Below are images of the bullet points I got in return, which tell me both what the paper is about and what I can learn from it:

The AI has identified the more general points that the article makes. It has managed to pull out some sentences that capture the thrust, if not the detail of the argument. So, the AI functions in the way it is intended. It could be said to work. It reduces the article down to some key points, making it rapidly digestible. To do this, it boils away both the detail and the less central arguments, leaving only the residue of ‘core ideas’. I wonder if in the end these core ideas are reduced to such an extent that they would become hard to differentiate from other articles in the same field.

It is highly likely that people will find a tool like this to be really useful and that it will aid people to grasp a wider range of research. Making articles accessible in this way might even enable students and researchers to tackle bigger problems, or find their way into new areas more easily. I hesitate though because I wonder what it will bypass.

The concern I have here is that the move to AI informed efficiency might actually end up cutting out the bits of research that produce all sorts of unexpected and unforeseen outcomes. Those moments when we spot something in the foothills of an article that triggers our imaginations might be erased. What if the AI summary leaves out the little nuggets that open up new directions? What if the little rough edges of research are where we find the ruptures that we can get hold of? The focus upon ‘core ideas’ inevitably leaves out the ideas in research that are not core, but which might yet be. And, of course, there are then the decisions being taken about what constitutes a core idea.

The act of summarising is not neutral. It involves decisions and choices that feed into the formation of knowledge and understanding. If we are to believe some of the promises of AI, then tools like Paper Digest (and the others that will follow) might make our research quicker and more efficient, but we might want to consider if it will create blindspots. Perhaps it will blur some alternative lines of inquiry, as we rush past them in a hurry to keep up with the pace that is being set for us.

Paper Digest is only at a beta stage and is an early stage technology, but its presence and framing tell us something about the wider ideas about research and learning of which it is a part. It may not be Paper Digest in itself that is a concern, indeed, it could be a useful tool, but its underpinning reasoning and ideals are part of a relentless push towards research efficiency and the acceleration of thinking. If left unchecked, we might well end up undermining the conditions that actually facilitate creativity, thoughtfulness and an eye for a good idea.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Featured image credit Robert Couse-Baker via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Isn’t this the purpose of an abstract? Also, some journals ask authors to fill a box summarising the state of play in the relevant field and what the submitted papers adds to that state of play. Of course this does not necessarily work across all fields, and probably least in the humanities. But it does force authors to think about their work and how best to succinctly communicate it in a fashion that is helpful to scholarly advance.

I tried this twice and it brought up the same article twice, which was incorrect – so I’ll let it off as it’s in Beta – but I don’t think we need to be concerned by our Systematic Review Robot Overlords just yet