In After Lockdown: A Metamorphosis, Bruno Latour explores how the experience of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic has led us to better understand our connections with other living beings, in ways that might be conducive to confronting our climate crisis. This book will be of interest to anyone wanting to explore the philosophical meanings of lockdowns, Gaia theories and climate politics, writes Rong A.

This blogpost originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the managing editor of LSE Review of Books, Dr Rosemary Deller, at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

After Lockdown: A Metamorphosis. Bruno Latour (translated by Julie Rose). Polity. 2021.

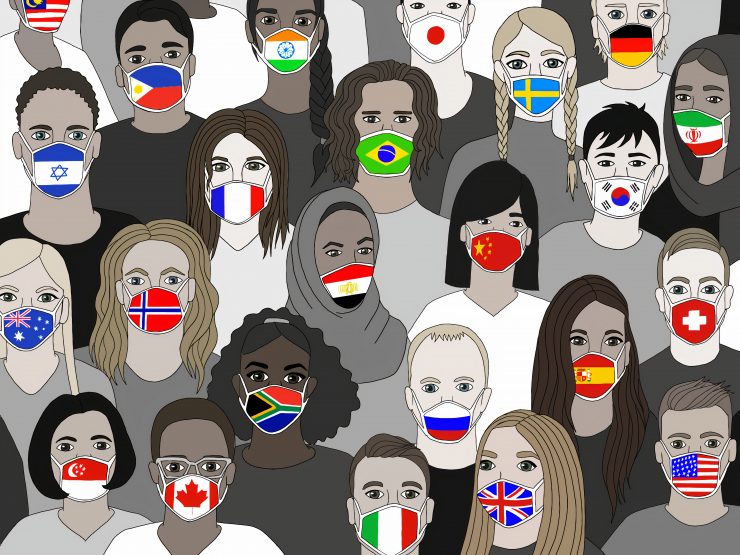

It is probably normal to have the desire to free ourselves from the suffocating masks and COVID-19 lockdowns. Yet Bruno Latour invites us to rethink this desire in his new book, After Lockdown: A Metamorphosis.

It is probably normal to have the desire to free ourselves from the suffocating masks and COVID-19 lockdowns. Yet Bruno Latour invites us to rethink this desire in his new book, After Lockdown: A Metamorphosis.

According to Latour, suffocating lockdown experiences are tragically interesting and empowering. During the lockdowns, humans have been going through a metamorphosis, like Gregor in Franz Kafka’s short story. Latour uses a number of concepts to describe this metamorphosis, including ‘Universe’ versus ‘Earth’, ‘Going Up’ versus ‘Going Down’ and ‘Old-fashioned Human’ versus ‘Terrestrials’. These are boiled down to the conflicts between a ‘Modern’ worldview and a ‘Gaia’ worldview, which sees the planet Earth as a living organism composed of multiple, reciprocally linked but ungoverned self-advancing processes (see also Latour’s book Facing Gaia and the readings recommended in Chapter Fourteen of After Lockdown).

In this sequel to Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Latour continues to explore the existential question: where am I? This question should be tackled before we discuss whether there are climate crises or how to cope with climate issues. Lockdowns provided a crucial answer to this question: humans are terrestrials living on Earth.

As Latour argues, before the lockdowns, people were not on Earth. One dangerous modern idea had emerged since Galileo that we were going to live in another world: the Universe (119). Science allows us to observe our planet from space. However, when we see Earth from a distance, we misunderstand our planet, as we can never see all the ‘engendering concerns’ on Earth: a term which generally refers to the connections, overlaps and interactions between diverse human and natural beings (23-24). NASA pictures erased ‘the compatriots, who, through their engineering feats, their daring deeds, their freedoms, are able to build whole compounds that they organise in their fashion and that are more or less interconnected’ (14-15).

Lockdowns provided a crucial answer to this question: humans are terrestrials living on Earth.

The modern history of the past three centuries is a process whereby humans have gradually erased engendering concerns. Modern emotions, such as progression, expansion, abundance and freedom, are assumed as normal. The interconnected engendering concerns shared among humans, termites, bumblebees, rocks, rivers and air have been buried. Empowered by assumed objective knowledge, humans have had the ‘secularised religious emotion’ (57) that they can escape from this world and don’t need to be held accountable for their expansions.

When humans denied engendering concerns, they became residents of the Universe. Earth, with a capital E, as Latour explains from a Gaia perspective, refers to ‘the connection, association, overlapping, combination of all those who have subsistence and engendering concerns’ (27). The Universe indulges the fantasy of expanding without confinement. An extreme example is Elon Musk, who is planning to take off for Mars through his company SpaceX.

The COVID-19 lockdown challenged a variety of modern emotions. Firstly, it disturbed the feeling of freedom. Born of the Universe, Moderns always wanted to deny their issues and escape elsewhere (53). Nevertheless, no matter how much people want to escape the lockdowns, they are confined between walls. This revealed a significant fact: we, terrestrials on Earth, cannot move without constraints. Latour describes his lockdown feelings:

‘I begin to position myself as a terrestrial among other terrestrials once the surprise has worn off and I realise that terrestrials never move around ‘‘freely’’ everywhere in some undifferentiated space. They construct that space step by step. […] it’s feeling confined that gives us this freedom finally to move ‘‘freely’’. Turning into a termite assures us that we can’t survive for a minute without constructing, by means of saliva and mud, a tiny tunnel that allows us to crawl in complete safety a few millimetres further along. No tunnel, no movement.’ (27)

Lockdown experiences are empowering as lockdowns shook off the secularised religions that preach escape from this world (57). On Earth, confinements have always been terrestrials’ direct experiences. Becoming an insect, as Gregor experienced in Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, is empowering as we free ourselves of the infinite. In lockdowns, people know perfectly well that there is no infinite exterior anymore (55), and everyone started to live at home but in a different way (53).

Before the lockdowns, people did not live anywhere in particular. They were living in globalisation or in the Economy, dreaming about freedom and continuity. Lockdowns grounded people somewhere at last. This is a part of the metamorphosis: people replaced the approach of ‘living in a globalised world’ with ‘let’s try and situate ourselves in a spot we’ll need to try and describe in tandem with others’ (70).

In parallel, lockdowns gave people a chance to free their minds from the laws of economics in which they were rotting away. As Latour mentions, in lockdowns, we have to cook for ourselves. We have to take care of our dependents. We have to rely on key workers to ensure the continuity of the most ordinary life. In many ways, we are becoming more realistic, pragmatic and materialistic. As Latour illustrates, we are no longer living in ‘the Nature invented by the economists so as to have their sums circulating freely in it’ (63). Rather than shouting about ‘restarting on the path of progress’, many people are thinking ‘what earth are we really going to be able to live on, my dependents and I?’ Humans are recognising the engendering concerns and the ties of interdependence among neighbours, insects and land. We are opening each discussion that the Economy aimed to close (76). These transformations made lockdowns positive.

lockdowns gave people a chance to free their minds from the laws of economics in which they were rotting away.

After the metamorphosis, will we have a different world? Latour thinks so. Earth is becoming a place that is different from the planet of Globalisation (where people are indifferent to the fate of earth), or the planet of Exit (inhabited by the famous 0.01 per cent who are privileged enough to run away from real-life issues), or the planet of Security (where humans are defined by borders and national identities). Instead, a new planet, Contemporary, is emerging after the lockdowns (104). Countless people are decolonising themselves at full speed. New political landscapes will emerge and include all agencies: every river, every town, every computer, every earthworm, every cell and so on.

With all these participants, planet Contemporary will have various ‘environmental controversies’ (114). From a Gaia perspective, the main conflicts on planet Contemporary will be among the Extractors and Menders. Terrestrials, as the Menders, will stitch together territories that Extractors have abandoned after having occupied and destroyed them. And they will do the mending job without any of the legal, mental, moral or subjective resources of the nation state. Political beings will not go straight ahead as Descartes advised but scatter as much as they can and explore their capacities for survival. Gaia is not ‘big’ or ‘global’ in the usual sense, but connected step by step (74). In Chapter Fourteen, Latour explains the development of these theories in detail and recommends a variety of additional resources.

In After Lockdown, Latour captures multiple sentiments shared by people in 2020-22 during the COVID-19 pandemic and uses these concrete experiences to examine the concepts of freedom, borders, globalisation and modernity. This book should be of interest to anyone wanting to explore the philosophical meanings of lockdowns, Gaia theories and climate politics.

In addition, for those interested in Earthly Politics and Latour’s work, you might like this online exhibition: https://zkm.de/en/exhibition/2020/05/critical-zones.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Forest Simon via Unsplash.