Global society is beset with many ‘wicked problems’ that are unlikely to be resolved by traditional disciplinary research methods. In this post, Kristina Bogner, Michael P. Schlaile and Sophie Urmetzer discuss the concept of transformative research and how it can be applied to create the conditions for a sustainable and just transition in mobility.

The empirical evidence is overwhelming. In the coming years, our social and ecological systems will undergo radical changes, and we must drastically limit our negative impact to prevent societal and environmental collapse. One sector that is particularly polluting and trapped in injustice is the mobility sector. These injustices against the environment and humans are characterised by unequal access to goods (e.g. to mobility) and exposure to ‘bads’ (e.g. to pollution) and unjust power relations. This is leading researchers and policymakers to increasingly call for and engage in sustainable and just mobility transitions.

However, the scientific knowledge currently produced to transform the mobility sector is failing in its aim to reduce pollution from transport and improve mobility justice. Why? Academic research traditionally follows a somewhat linear knowledge creation and dissemination process. Mobility research programmes are designed around influencing metrics like ‘number of passengers’ or ‘shares of different modes of transportation’. As long as mobility practices are not scrutinized, and people’s routines as part of their lifestyles do not feed into mobility research, the scientific output will necessarily lead to a disconnect between knowledge and action, or a ‘theory-practice gap’. In addition, mobility research has frequently focused on finding technological solutions (e.g. substituting combustion engines with battery electric vehicles), which on their own fail to reach the desired sustainability goals.

From the perspective of sustainability transitions research, this is hardly surprising, as linear and technology-centred approaches frequently underestimate the complexity of systems and the “wickedness” of problems. For example, problems can be “wicked” in the sense that there is no clear or uncontested problem definition, wicked problems are strongly interconnected (attempting to solve a problem may worsen others), and there might be no right or wrong way to address them. If we want to transform by design rather than by disaster, dealing with such challenges requires a different take on (the role and responsibility of) research.

Three key dimensions of transformation

When aiming to better understand and inform intentional interventions in complex systems, it is necessary to consider the interplay of at least three dimensions of transformations. In our global, networked societies, the direction of desired changes is neither uncontested nor is it clear who has a mandate and the power to instigate systemic change. In other words, we must address:

1. Directionality: Where do we want to go and which parts of the system (people, institutions, mechanisms, values) need to change to get us there? For example, what exactly do we consider just and sustainable mobility, and which (parts of the) mobility systems must be transformed (provocatively put, should we all stop travelling or equip everyone with an electric car)?

2. Legitimacy: Who has the “right” / authority to decide why we should change anything anyway – and on which grounds? For example, should a ministry of transport, or car lobbyists, or mayors, or ‘the market’ decide what future mobility looks like?

3. Responsibility: Who holds power to change the system, who benefits, and who can / should be held accountable? That is, which individuals, groups, or organisations have the power (and thus share responsibility) to co-create responsible business and innovation (eco)systems (e.g. not just including car manufacturers, but also policymakers that can introduce emissions-reducing speed limits and consumers, who can opt for more sustainable transportation modes or publicly demand more sustainable mobility options).

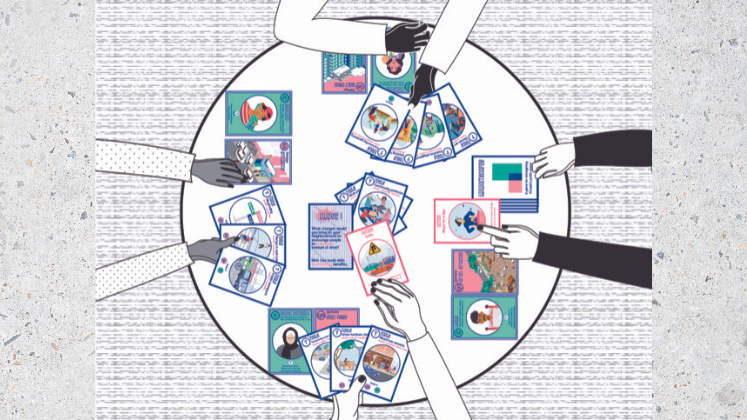

Transformative Research (TR) aims to directly engage with these factors, to overcome the knowledge-action gap and work in integrative ways with different types of knowledge. Transformative Research addresses persistent societal problems by engaging with different societal actors in a co-creative research setting. Examples of such research practices in the mobility context are manifold and include, for instance, participatory action research, agent-based transition modelling, sustainable urban mobility living labs or real-world labs. In these projects, researchers partner with citizens and other stakeholders to build a shared picture of the concrete dynamics and processes shaping local mobility systems and underlying injustices.

Transformative Research aims to directly engage with these factors, to overcome the knowledge-action gap and work in integrative ways with different types of knowledge.

Instead of accumulating knowledge for societal problems as defined by academia, transformative researchers are guided by these co-created visions. The acknowledgement of different perspectives, knowledge, alternative problem definitions, and new types of legitimate methods and solutions is necessary for taking different dimensions of justice into account: procedural, recognition, distribution and epistemic injustice. Transformative Research thus also helps to better understand the directionality of transformations and make explicit researchers’ legitimacy, since incorporating pluralist perspectives also helps to identify who has a stake in the transformation and who has the “right” to decide.

This research practice blurs the boundaries between different forms of expertise by bringing together relevant stakeholders to take responsibility for the necessary change. Thus, it explicitly commits to a systemic perspective that explores the dynamics and root causes behind “wicked problems” by identifying the structures, cultures, and practices within the system that need to change. A ban of private cars in a city, for example, is difficult to legitimize since it only addresses the symptoms of traffic jams. The root causes of the massive individual motorization, however, can only be tackled by the collaborative deconstruction of the system-induced individual necessities of the drivers.

Transformative Research is most effective as a complement to, rather than a replacement for basic research.

Transformative Research challenges the conventional linear understanding of knowledge production, dissemination, and implementation, as it values sharing of responsibility and a commitment to action, instead of engaging in an independent, unconstrained search for ‘truth’. Expertise in TR therefore produces new ways of thinking about and organising mobility in individual and social life. For example, by creating spaces and opportunities for citizens and other stakeholders to collaboratively envision more liveable communities for all. This approach can enable solutions way beyond technological ones and usually starts by challenging our narrow views on how we can change the systems within which we live.

Importantly, TR is most effective as a complement to, rather than a replacement for basic research. This requires what has been described as a ‘‘new social contract’ between academia, society, economy, and nature – a contract that levels researchers with their ‘clients’ and focusses on building new relationships. By conducting research with people instead of research about people, Transformative Research helps us to embrace science’s responsibility for contributing its share to a just and sustainable future.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Joseph Chan via Unsplash.

Thanks. The trouble with research in universities is that so-called ‘transformative’ research rarely gets funded.

Thanks, SP! Funding is a central issue, indeed. Revising funding schemes and developing new ways of funding beyond the traditional project funding etc. is one important part of that new social contract. In this regard, we’re quickly touching the topic of transformative innovation policy (especially in relation to research policy, incentive structures, hiring, promotions, and evaluation based on metrics beyond publications, etc.)….