Racist and classist mechanisms within higher education are often presented as abstract intangible processes that produce unequal outcomes for those attending university from non-traditional backgrounds. Drawing on evidence from their new book, Kalwant Bhopal and Martin Myers, argue whilst racism and classism can be systemic, it also directly and in plain sight supports and rewards the already privileged.

We hear a lot about classism and racism in the Academy being a covert practice. Inequalities are blamed on institutional or systemic biases. They are identified as the consequence of failings within the system rather than expressions of individual prejudice.

The term institutional racism sprang to prominence during the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. It is defined as the, “collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin”. Stephen Lawrence’s murder revealed how the collective failure of the Metropolitan Police ensured his killers were not brought to justice.

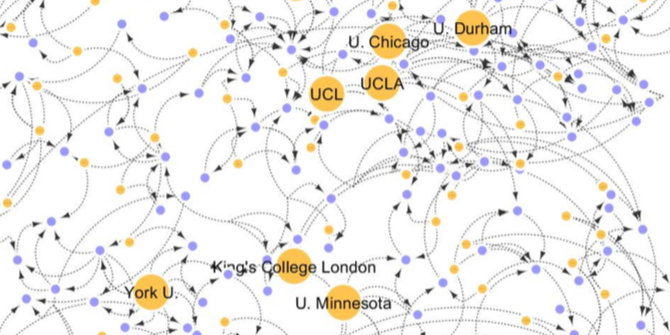

In our new book, Elite Universities and the Making of Privilege we argue that elite universities share many characteristics of institutional racism and institutional classism. They are exclusive organisations that have historically restricted access to ethnic minority and poorer students in both the UK and the US. Students from less privileged backgrounds often feel out of place and when they leave it is often with less successful grades than white, privileged peers.

At the same time there is a raft of evidence detailing the poor experiences of academics at elite universities, who do not fit the institutional mould. They face similar experiences of exclusion and often find it hard to progress their careers.

In our research students from non-traditional backgrounds described just how difficult an experience it could be working and succeeding in these institutions. One mixed heritage student, Ria, was the first member of her family to attend university. She made the startling admission that despite a literally unblemished record of A and A* grades in her GCSEs and A Levels, graduating with a first-class degree from a Russell Group university and having been offered funded doctoral positions at three elite universities, she still felt, ‘out of my depth here’.

Reflecting on her past achievements Ria suggested, ‘It’s just enough to get me here. But it’s never enough. To be here and to feel at ease being here. To be safe it’s not enough.’

Ria described feeling overlooked or side-lined by academics and other students. Teaching or research work that was routinely offered to white, middle-class students never seemed to come her way. She described being excluded from opportunities that would improve her CV in the future.

Students like Ria recognised the value of a degree from an elite university for them personally, however they also recognised it was not as valuable as it was for white, middle class privileged students. This was echoed by another student, Keira, who identified as being from a working-class background,

‘I want to be here. I’m just not convinced anybody else agrees.’

Perhaps the most striking fact about inequalities fostered at elite universities is that they are out in the open. These inequalities happen in plain sight. Even students who were from more privileged backgrounds candidly explained their natural fit with the institution. Describing his prior attendance at an elite private school in which all his teachers had also attended either Oxford or Cambridge Tony noted,

‘I’m very at ease in this sort of environment. It would be odd if I felt I did not belong here.’

To be shocked by the latest revelation of inequality at an Ivy League or Oxbridge institution is therefore entirely misplaced. It happens in open view. It fills newspaper pages on a regular basis.

Within academia there is a tendency to attribute inequalities to neoliberal economics, marketisation and managerial creep across the higher education sector. Evidence of prejudice is characterised as the consequence of the changing economic conditions in which universities function. It is another complaint to add to those of precarity, poor pay and dwindling pensions that can be laid firmly at the door of Vice Chancellors and their brigades of well rewarded senior managers. In our book we argue that this is not entirely true. This is not to suggest that systemic, institutional racism and classism do not exist: they do. However, these analyses often appear to provide an excuse, either to blame those higher up the food chain, or to explain that individual academics are not complicit in such behaviour.

Understandings of systemic or institutional inequalities are used to suggest these are issues that are somehow hidden from view. So for example, an academic making abusive racist comments is readily understood as an overt form of racism. Whilst a college that continually recruited low numbers of Black students would be an example of covert, institutional racism. The actions of an abusive racist are readily addressed because they are seen by everyone. Low recruitment is understood differently. It acquires a covert status that somehow happens out of sight and is therefore difficult to address.

The argument that these are covert inequalities is entirely untrue. The evidence of colleges not recruiting Black students or students from state schools has always been in the public domain. It is however used to excuse the lack of progress made by elite universities to put their houses in order.

What became apparent throughout our research was the alignment of systemic racism and classism with the interests of a wide range of white, middle class privileged students and academics at elite universities. Students experienced racism and classism because elite universities actively work to protect their own. They are designed to ensure elites continue to prosper.

All names have been anonymised. Elite Universities and the Making of Privilege: Exploring Race and Class in Global Educational Economies is published by Routledge.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Adapted from Victoria Heath via Unsplash.

Sad but true. Furthermore, the anti-establishment mind is often subtly censored in these universities. Critical thinking is muted rather than fostered. We’re forced to clap the neoliberal model and anglosaxon narratives, specially pro-US speech.

Food for thought!

Thank you for this insightful research.

I opine that it is more important to strengthen and build global South knowledge platforms than to continue the push to have global South voices on global North platforms

With life experience comes wisdom, with wisdom comes enlightenment. The most beneficial component of enlightenment is the deconstruction of ego (aka, identity). With that process comes peace of mind and more connectedness with everything, which is what we’re all looking for anyways. Academia, for reasons I don’t understand, is trying to get that result by embracing the one thing that’s sure to prevent it.