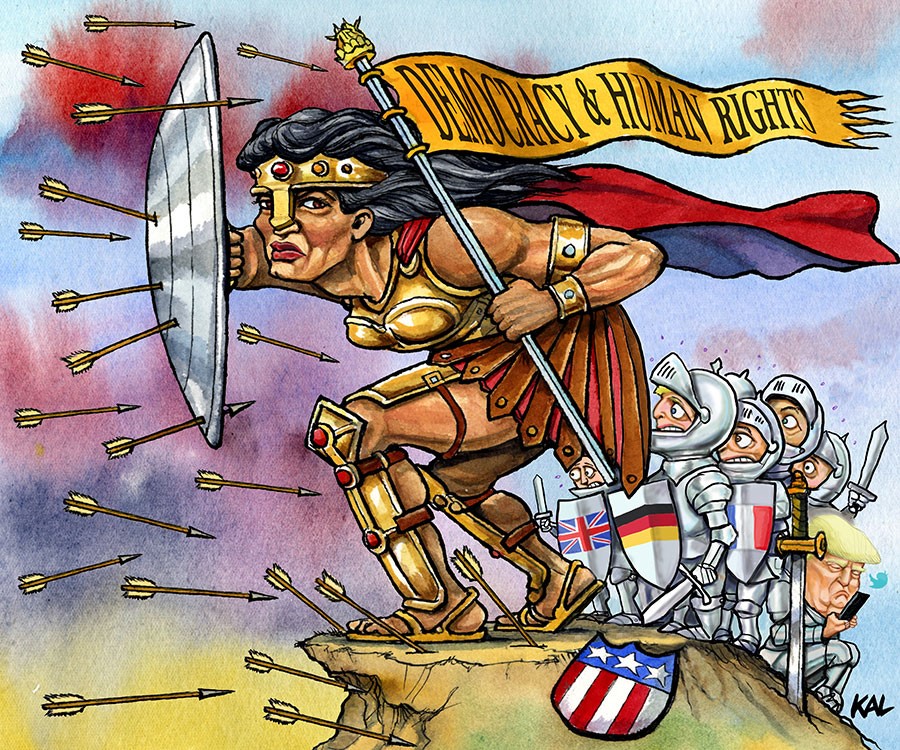

MSc Political Economy of Late Development, Dhruva Mathur, responds to a recent article by Dani Rodrik which suggests that Western countries are under threat from the distorted notion of “liberal democracy”.

In a recent article in Project Syndicate, Dani Rodrik boisterously proclaimed the threat that Liberal Democracies faced from the “panoply of restraints that limit the range of policies they [rulers] can deliver”. These restraints result from the institutional arrangements – the bureaucracy and other actors – that have been put in place to facilitate the implementation of policy. Yet, such a view ignores that dangers heralded by populist politicians, liberal or conservative, if bestowed the authority to completely implement their policy vision. Hence, these restraints are not threats to the present-day systems but are instead media for ensuring continuity and progressive change instead of abrupt and impulsive change.

Before putting forth any argument in favour of the institutions in place, one must of course acknowledge that these institutions do have the ability to impede change, good or otherwise. It is after all these very institutions that Pei believes will be at the frontlines of resisting President Xi’s reformative agenda in China and which continue to impede the implementation of President Trump’s agenda in the United States through judicial reviews.

The technocratic bureaucracy, due to their permanence, is also able to resist the short-term mentality that democratic governments tend to have. The best case in point is the Indian Railways. Till recently the Railways in India was used as a tool for currying political favours with the voters by ensuring limited price hikes. As a result, not only was there a gross neglect of capital investments in the sector but questions could also be raised about the capacity of the existing revenue systems to maintain the current capacities. Consequently, the advent of a technocratic model in the form of the Rail Development Authority, to decide fares free from political influence, is a step in the welcome direction. Nonetheless, this is only one of the many economic rationales for the growing authority of bureaucracies. Economic rationales to support such authority are likely to be similar between the west and the east, the differences emerge when the socio-political differences are taken into account.

However, Rodrik tends to ignore such impact that institutional actors tend to have in determining the policy space through their role as watchdogs in societies divided by the cleavages of identity and wealth. While these are indeed arguments in favour of the inherently stabilizing characteristics that institutions endow states with, they are portrayed as being in the way of the establishment of a liberal democracy.

Yet, this classification of liberal democracy has within it the many western biases that have increasingly become associated with the understanding of the state. Liberal democracies in multi-ethnic, religious and linguistic states operate under a completely different prism. They are constantly in the process of securing the Best Alternative to a Negotiated Arrangement (BATNA). In these circumstances, the role that these institutions play in maintaining stability gains utmost relevance.

The spectre of conflict promulgated by identity cleavages is an ever-present reality in the heterogeneous societies of the global South. Liberal Democracies do not retain their western epistemological roots in such a scenario. Rather, they evolve to encompass something more – the ability of different groups to peacefully coexist while ever expanding their scope for freedom of expression and choice. Here, freedom of expression does not retain the sensibility of being absolute in scope, but rather as a negotiated gradual movement towards absolutism. Thus, looking at Liberal Democracies from the single lens of the west, is likely to confuse many of the gradual and negotiated marches of Liberal Democracies as being deformed instead of encouraging.

Consequently, the bureaucratic and institutional arrangements work to secure this gradual advance of free speech. In this process, they secure the most intrinsic element within the term, Liberal Democracy: Democracy. Portraying majorities as being issue based, like the Brexit results, is a narrow analysis of the role of identity. By limiting policy space available to elected officials, institutions are able to ensure that the identity cleavages do not gain policy salience, which would result in an unequal distribution of not only economic gains but also of unequal prevalence of social policies of a select few groups, religious, linguistic and others.

If not limited, open policy spaces can be breeding grounds for conflicts in divided societies. In this respect the European Union is similar to much of the heterogeneous global south. As a nascent political union composed of a multitude of identities, the bureaucracy is required to be a bulwark against the fickle nature of political parties and their agendas, once in government. The brilliant administrator Sir Humphrey, of Yes Prime Minister, succinctly described the consequences of increased policy space for the fickle agenda of elected officials as resulting in a “stark-staring raving schizophrenic” bureaucracy and country. Thus, it would be fair to argue that institutional and bureaucratic arrangements that limit policy spaces are in fact the silent guardians and vanguards of Liberal Democracy and its negotiated progressive march.

Dhruva Mathur (@Dhruva_Mathur) is an MSc Political Economy of Late Development candidate at LSE. Prior to this, he completed a Master of Public Policy from the Hertie School of Governance, Berlin. He has conducted research on the legitimacy and economics of fragile states and plans to undertake future research on the role of institutions and other factors in determining the economic trajectory of a country.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Thank you for putting into words my unease with Rodrik’s argument.