MSc Development Management student Sharon Sagues, tells us about her recent group project for Policy, Bureaucracy and Development (DV450), which looked at the role of ICT in education by analysing the specific case of One Laptop Per Child in Peru. You can read their full report here.

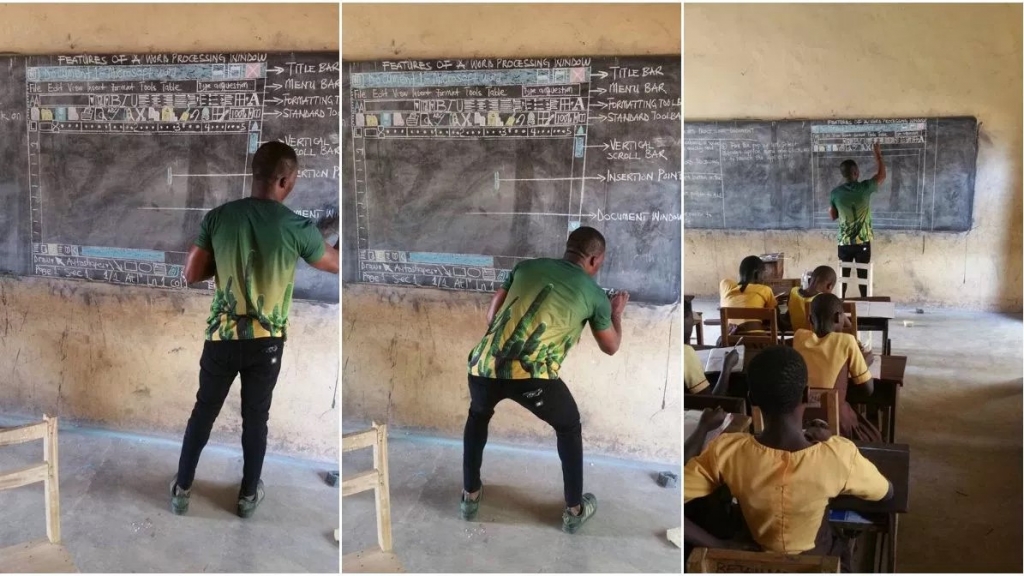

Recently, the viral story of a Ghanaian school teacher has inspired many for his perseverance. Richard Appiah Akoto has been teaching computer software using a blackboard as his only interface. Although inspirational, his story has also reminded people of the deplorable conditions in which education is still delivered in much of the global south. Influenced by the widespread impact of the story, Microsoft Africa pledged to send Mr. Akoto a computer with full access to the company’s educational material.

This is a wonderful response that will surely improve the teacher’s capacity to deliver his class, which is particularly relevant given that students are expected to pass a national exam testing ICT proficiency. However, we must not forget the bigger picture: this story is also a reminder of the role that material resources play in development. Does it make a difference to donate such resources? What is their purpose? Can society progress through their provision?

As part of our course on Policy, Bureaucracy and Development we were introduced to the concept of isomorphic mimicry. This concept has been used previously to refer to the natural world and how some animals can benefit for survival by looking like other animals. An example given is that of a non-venomous snake imitating the looks of a venomous one, without having to actually develop the mechanism for poison.

Adapting it to the policy context, Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock questioned the implementation of so-called “best practices” in many diverse contexts, especially when the latter was disregarded. The authors challenge the standardised approach where governments put more emphasis on the form of their policies, rather than the function. Moreover, they acknowledge that isomorphic mimicry can be a very attractive strategy! As it is often easier for governments to change merely what they look like, instead of the profound reforms needed to change what they do.

This notion resonated particularly when looking at the case of ICT use in education. The belief in ICTs’ great potential for effective learning and the development of more efficient education services has actively been pushed by multilateral agencies in global initiatives. As a result, ICTs in national education policies tend to be subject to ambitious development goals despite all the pedagogical concerns and challenges to educators and administrators. With such bold goals, for which many developing country governments lack the state capacity to implement, falling into isomorphic mimicry becomes a likely risk.

For our final project for the course, my group and I analysed the specific case of the intervention of MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte’s One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) by the Peruvian government. OLPC assumes that, by providing laptops with educational content for individual use of the children, self-empowered learning will naturally ensue. The expected results? Helping eliminate poverty and moving towards world peace.

The Ministry of Education of Peru adopted this scheme in 2008, seeking to provide the low-cost XO laptops, designed by OLPC, to all primary public schools in low income areas. Priority was given to rural multi-grade schools with single teachers. The programme made Peru the largest purchaser of XO laptops worldwide.

With such a large purchase, access and provision of technological equipment (evidently) increased. This was considered beneficial in keeping with the government’s evaluation criteria, based mainly on the number of laptops distributed. Could the programme, then, be considered successful? In spite of having technological tools now, Peru did not see improvements in the quality of instruction in class: studies have shown that the provision of laptops did not significantly increase the learning of Maths or Language, for example. How did this happen?

We argue that the Peruvian government did not manage to avoid isomorphic mimicry. Firstly, by focusing most of the budget on the acquisition of the laptops rather than on adapting its implementation to local conditions, there were insufficient remaining financial resources after the purchase of the laptops to integrate the software, adequate security measures, training, and pedagogical strategies into the educational system. Secondly, by following a centralised implementation of the policy, local governments were not considered in the formulation and implementation of the programme—not to mention the lack of proper training that would have allowed actual integration of the technology into pedagogical practices. In fact, only 10.5% of teaching staff reported having received technical support and 7% for pedagogical support for the implementation of the programme in school. Finally, given the impulsive mass buying of laptops followed by a short-lived pilot—in addition to the absence of periodic assessments of the impact of the programme—the Peruvian government lacked adequate experimental learning and feedback.

Isomorphism creates a fundamental mismatch between the expectations and the actual capacity of systems, leading to unrealistic demands that weaken the state’s capabilities. Eventually, the state becomes vulnerable to the capability trap, where state competency deteriorates even though the resources are available and development is prioritised.

The case of Peru’s implementation of ICTs in education is not a new or unique one, but still serves as a helpful reminder of how material resources and aid can only help to a certain extent in creating developmental impact. Material resources, on their own, are insufficient. Any developmental intervention necessitates profound considerations of the specific context that one is dealing with. It is good to have the form, but the purpose is the function, and the former must adapt in benefit of the latter.

____

Link to full report: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/internationaldevelopment/files/2018/03/DV450_OLPCPeru.pdf

MSc Development Management students Rebecca Turczynowicz, Prakriti Gautam, Arniela Rénique, Charis Yeap Khai Leang and Sharon Sagues, analysed the problem of submitting public policy to “best practice” models, as can be the case of ICTs in education. Their report was a requirement under DV450: Policy, Bureaucracy and Development: Theory and Practise of Policy Design, Implementation and Evaluation. The analysis was done using the concept of isomorphic mimicry and the case study of One Laptop Per Child in Peru.

Sharon Sagues is an MSc Development Management student from Mexico. She is particularly interested in the role of education in development, as well as other development topics.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.