On Friday, 15 February, Barbara Harris-White from Wolfson College, Oxford, gave a timely talk on “Development, Big Business and the Environment” for the International Development Department’s Cutting Edge Issues in Development lecture series. Here’s what MSc Environment and Development student, James Diffey and part-time MSc Development Management student, Celine Zins took away from the lecture.

We could not have been treated to a more topical lecture on Friday evening, the day of the “Youth Strike 4 Climate” protests involving 15,000 pupils from across the UK. Although Barbara Harris-White was keen to highlight the broad range of environmental issues development practitioners ought to consider (ranging from ocean acidification to habitat destruction), her primary concern was clearly the climate change threat.

Scepticism about the reality of climate change is often capitalised on by powerful individuals and institutions pursuing their own agendas, but the science behind it is (unfortunately) robust. That has been the conclusion of (multiple of) the IPCC’s Assessment Reports, which synthesise the findings of leading climate scientists from around the world. Climate change is now arguably the biggest threat to livelihoods in the world. Climate change has already had acute impacts on communities around the world, ranging from indigenous communities in the Arctic and rural farmers in India to the entire populations of small island nations. Indeed, the so-called ‘developed countries’ have not proved immune either. Heatwaves across Europe and wildfires in the United States have been made more frequent and more threatening by climate change, although they are too often misunderstood as unrelated.

As Barbara recognised, the sooner we act on climate change the better. Climate change requires immediate action to minimize short and long term damage. Heat-trapping greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide remain in the atmosphere for decades after they are emitted and there is only so much we can emit if we are to prevent catastrophic warming. Our collective failure to reduce these emissions is essentially procrastination on the most important issue of our time.

Beyond learned helplessness

Most people that I interact with care deeply about climate change but are overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge and try to put it out of their minds. Particularly when others do the same, it can seem easier to bury our heads in the sand and downplay our own responsibility, than it is to accept that we have the ability to make meaningful changes.

The actions we take to mitigate climate change can literally save lives. For true change to occur, we need two main things. Firstly, at an individual level we need to make an effort to tweak our diets and travel habits. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, we all need the courage to speak out about this issue that concerns so many of us.

James Diffey is an MSc Environment and Development candidate passionate about climate change mitigation. His research interests include behavioural change and effective environmental advocacy.

_______________________________

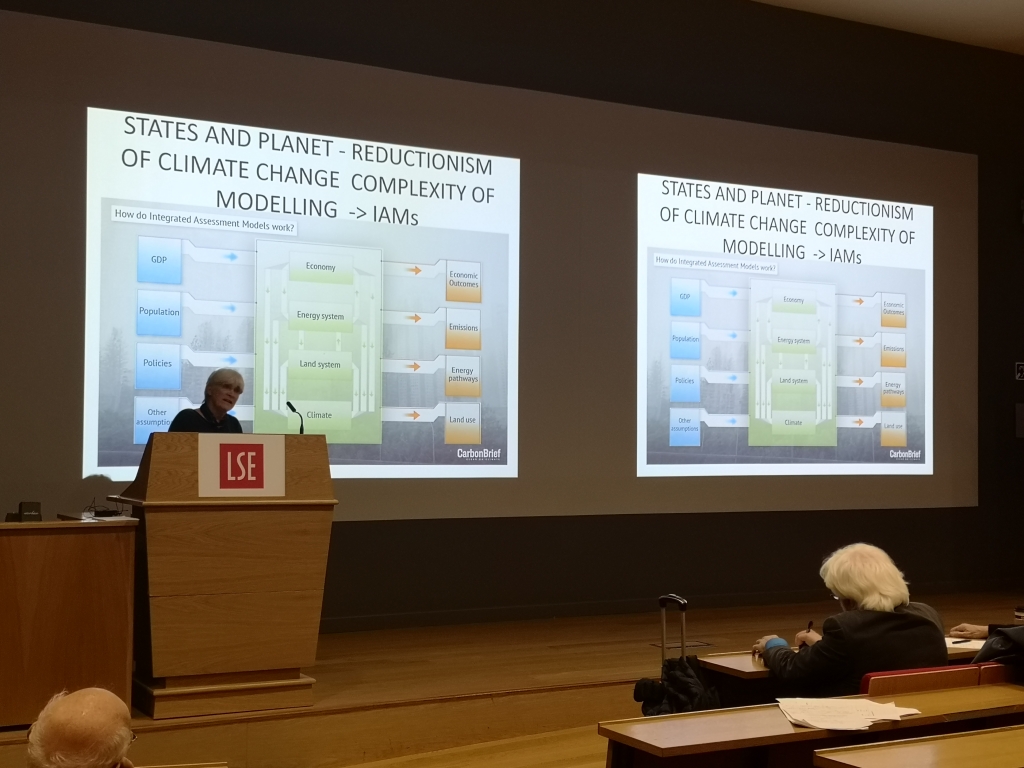

As school pupils across the United Kingdom marched for government action on climate change, International Development students at the LSE listened as Professor Barbara Harriss-White from University of Oxford delivered a lecture on the understanding of and potential solutions to the ecological crisis within a globalised, capitalist context.

Starting with a focus on the planet’s finite capacity to absorb used resources, the conversation quickly turned to problematic conceptions of climate change, like the integrated assessment models (IAMs) used by scientists and economists to inform global policymakers’ decisions. IAMs such as those used in the IPCC’s October 2018 1.5°C Special Report, explains Harriss-White, act as a ‘comfort blanket’ by including an overshoot window, ignoring avoided climate damages and relying on the assumption that necessary decarbonisation technologies will be fully developed and commercialised in the very near term. In addition to the implication of a continually receding deadline for climate action, an important limitation of IAMs is the least-cost paradigm, whereby models test least-cost scenarios to meeting policy goals. Politics is rarely about minimising cost per tonne of CO2, but often about what is easiest to deliver.

Barbara Harriss-White asserts that orthodox conceptions of climate change and their accompanying market-based solutions such as carbon markets are problematic in that they ignore the politics of big business as well as the historical and economic logic behind the production of capital. If 20 companies are responsible for a third of all historical greenhouse gas emissions –and control the majority of fossil fuel reserves on the planet, why are these companies not actively taking part in resolving the ecological crisis? It is up to states, we are told, to collaborate with both businesses and civil society to be the material force behind the politics of change.

Although a sense of urgency and need for coordinated action are convincingly conveyed, what appeared to be lacking from the discussion was attention on the impacts of a rapidly growing population and evolving consumer preferences on the environment. As mobility increasingly takes a central role on the climate agenda, business-lead technological advances may well be for sustainable transport the success story that collective action was for ozone healing.

Celine Zins is a part-time MSc Development Management student at the LSE, working in environmental compliance and macroeconomic analysis for an EPC contractor. A Development Economics graduate from SOAS, her interests include the history of growth and competition theories as well as the nexus between development and environmental degradation.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.