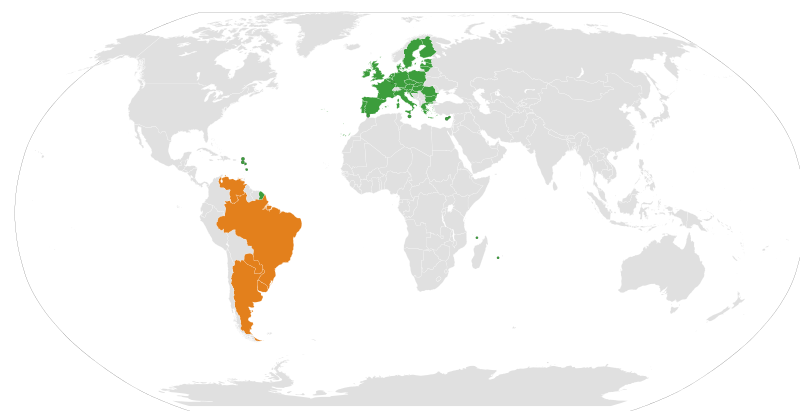

Guest blogger Marcus Walsh, postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) Europe, questions whether the EU Mercosur framework protects the Amazon Rainforest or if it has exacerbated the prioritisation of business interests.

In reacting to the recent fires in the Amazon as a result of prioritization of business interests by the Brazilian administration, the EU Commission has stated that the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has put the EU-Mercosur trade deal in jeopardy. To expand the domestic economy through greater access to land, the Bolsonaro administration has promoted business interests through environmental deregulation while marginalizing indigenous groups of the Amazon. As one of his first political acts as President, Bolsonaro placed the Ministry of the Environment under the control of the Ministry of Agriculture. The merger of the two ministries has allowed the Bolsonaro administration to push through the political interests of the domestic and international farming lobby.

As a response, Ireland and France have threatened to pull out of trade negotiations with the Mercosur trading bloc. The political statements from both countries are a reflection of the public outrage from environmental groups and the greater public throughout the globe as a result of Brazil’s lack of commitment to the environment.

President Macron’s statement that the Brazilian President “lied to him” about his commitment to climate change as part of the Mercosur trade deal has been interpreted by critics in Brazil as Macron’s political strategy to gain visibility and political control at the G7 summit. Also, critics feel that Macron has been opportunistic by taking advantage of a changing discussion in Europe on the environment for his own political success.

The EU is right to place blame on the current Brazilian administration for environmental mismanagement because the EU-Mercosur legal framework in the trade deal has exacerbated the prioritization of business interests and has helped manipulate the domestic environmental agenda.

The fires in the Amazon have placed Brazilian domestic politics and the EU-Mercosur trade deal at the forefront of global politics. Threats from European countries to pull out of the trade deal hinder the development and strengthening of environmental policy and economic sustainability. They also challenge the sovereignty of the Brazilian state which could have severe ramifications on developing future trade deals.

The changing political rhetoric at the G7 summit raises the question: How committed is the EU on prioritizing environmental policy in the trade agreement? An analysis of the EU treaty law and the trade deal demonstrates clear signs that loopholes are enacted to protect European business interests in the addressing of environmental obligations.

To get serious about environmental obligations, the EU and European countries need to address regulatory capacity and the decentralization of institutional oversight in the trade deal to reassess its environmental obligations.

Last year, I published an article on the EU-Brazil relationship in its environmental obligations to trade. The legal framework in the trade deal places greater pressure on the Brazilian federal government to prioritize trade interests over environmental obligations and creates a stopgap for domestic institutions to act toward environmental regulations. As a result, the Brazilian federal government has taken advantage of the Brazilian Constitution to transfer the responsibility of implementation of environmental obligations to federal states. This has placed the economic and political risk on already fragile local municipal governments. Hence, the decentralization of regulatory capacity to federal states has weakened oversight in the Amazon. On top of that, the decentralization of regulatory authority limits the Brazilian federal government’s ability to act in a time of crisis.

The EU has not taken action despite the importance of a commitment against deforestation as addressed in environmental obligations. At the same time, Brazilian institutional inaction regarding trade in fear of environmental sanctions would cause the EU to create environmental commitments without forcing Brazil to uphold its ecological obligations. This has put pressure on the Brazilian government to reform its environmental policies. In essence, this places the monitoring of the environment on the Brazilian federal government and limits the political exposure of the EU.

For substantive change to occur, the following needs to take place:

First, for the EU to be serious about environmental policy in its trade relationship with Brazil, there must be a re-evaluation of trade concessions that create environmental policy stagnation. Effective trade concessions will strengthen individual rights, property rights, and provide greater autonomy to regulatory agencies.

Second, the EU needs to strengthen regulatory mechanisms in the EU legal framework and its institutions regarding trade and the environment. This will strengthen the regulatory capacity in the strategic relationship between the EU and Brazil. As of right now, there is little political will to enact comprehensive regulatory oversight due to the lobbying of business interests and the lack of political will to invest capital and resources in regulatory institutions.

The pro-environmental rhetoric from the EU and European national politicians will not be enough to affect change. It will be up to the political will of politicians, domestic and international business interests, and environmental groups to strengthen environmental obligations in current and future trade deals. To pull out of the trade deal is not an effective option.

Marcus Walsh-Führing (@WalshFuhring) is a postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) Europe (@JHU_BIPR). Marcus’ research interests focus on EU Foreign Policy, revenue collection, corporate governance, and regulatory autonomy.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.