Professor in Practice in the Department of International Development and Senior Strategic Adviser at Oxfam GB Duncan Green argues for Open Access publication. This post was originally published on the From Poverty to Power (fp2p) blog.

Finding myself having a repeat conversation with a number of different colleagues is usually a sign that a blogpost is warranted. In recent months I have had a series of chats with people either planning or already well into writing a book. The conversation usually goes something like this:

Me: have you thought about Open Access?

Them: Gimme a break – I need to write the book first, I’m still wrestling with the ideas and trying to find a narrative. Publishing details will have to wait.

Me: If you wait then it’s too late.

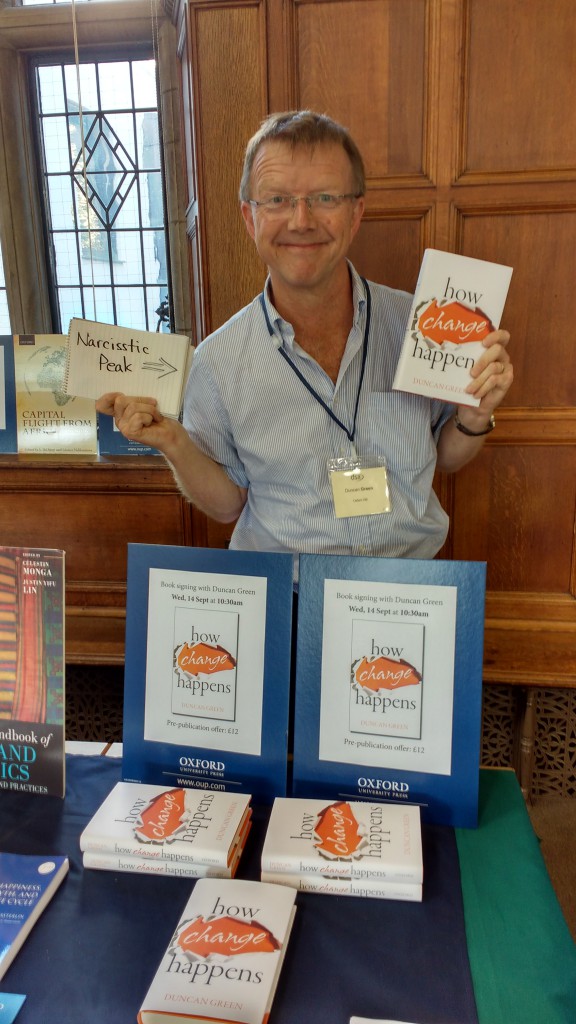

The case for Open Access. My last two books, From Poverty to Power (2012) and How Change Happens (2016) were both OA, and the stats were convincing. I haven’t done the numbers for HCH this year (there’s a limit even to my narcissism), but in the first four years (to October 2020) the ratio of hard copies to free pdf downloads to online reads was 1:5:15. In real numbers, the book sold 10,000 copies, 50,000 people downloaded the pdf, and 150,000 read anything from a paragraph to the whole thing online.

Not only that, but OA ensures a long tail – hard copy sales tail off after a couple of years, but downloads and online reads just keep rising.

Convinced? That’s just one book of course, but it’s consistent with the findings of research on much larger numbers of OA books, which found that ‘Downloads of OA books were on average 10 times higher than those of non-OA books, and citations of OA books were 2.4 times higher on average’. And it’s probably even more true if, like me, you are trying to reach readers in low and lower-middle-income countries, where the paper book trade is often pretty rudimentary.

I recently had a comradely spat on twitter with friends at the Institute of Development Studies on this topic.

IDS: In this episode of #IDSbetweenthelines @ptaylor_ottawa interviews @dannyburns2@johoward_ch and Sonia M. Ospina editors of the book: The SAGE Handbook of Participatory Research and Inquiry Listen here.

Me: Perhaps something a little contradictory in a £265 book on participation? Isn’t it time we (research funders and academics) all took #openaccess for books a lot more seriously?

IDS: Yes, we fully recognise that the cost of the handbook, and the more affordable e-book option, are a substantial investment. With 71 chapters from 150 authors, it aims to be the resource on participatory methods for years to come. The editors have worked with the publishers SAGE to make the first chapter available for free (via link) and authors are able to share their chapters for teaching purposes. IDS is highly committed to open access publishing and we aim to achieve that wherever we possibly can.

Now I love IDS dearly, which after all was one of the first development institutes to set up an open access programme for its own publications. Since 2013 it has had over 7 million downloads – not views. And the podcast is great – they even did one on How Change Happens. But in this case, giving away 1/71 chapters for free and allowing authors to send chapters to their mates is pretty feeble IMO (but see editor Danny Burns’ spirited response in comments and come to your own view).

What all this suggests is that the discussion on OA in books is maybe a decade behind that on academic journals, but it is following similar lines, according to an excellent recent piece on the LSE Impact blog,:

- Publishers are introducing ‘Book Processing Charges’ for authors to cover the lost revenue. BPCs are typically £5,000 to £12,500 per book.

- Research funders are starting to insist on Open Access for books, as they have long done for academic journal papers

- A bunch of new academic presses have appeared that are dedicated to OA publishing

It’s not just Open Access though. Lots of authors seem blissfully uninterested in the price attached to their books, then complain when it appears in some £80-a-copy, libraries-only academic list. Why didn’t you ask? I was too busy writing the book.

Let me repeat: if you end up writing an £80, non Open Access book, you’re basically saying this is just for universities, and you’re happy with selling 400 copies. That’s both elitist and needlessly minimises your readership (and your impact – remember the REF!). It looks like you don’t care whether civil society organizations or activists read your book.

If you are outside the walls of the universities, it’s not just about the money, but also the hassle factor of paying online, reclaiming expenses if you can be bothered etc – you’re much more likely to go elsewhere for info, or just read the reviews.

If you care about the impact of your work – i.e. making sure that someone beyond the magisterium actually reads the result of all your pain and suffering – then you have to think about OA (and pricing) from the start, and negotiate with the publishers upfront. If you sign a contract and then say years later ‘oh by the way, would you mind doing this Open Access?’, your leverage is roughly zero.

And if you’re not thinking of writing a book, you probably have friends who are – please spread the word. And you might want to check out Open Access week, which is going on right now.

End of rant.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main image credit: Eugenio Mazzone on Unsplash. In-text image credit: Duncan Green.

Thanks Duncan for a much needed reminder about how important this issue is. I completely agree. But any discussion of this subject also needs to acknowledge and engage with the woeful exploitation of academics by publishers. Particularly young academics who are told they need to get a book published and have very little negotiating power. Even at the start. As with journal articles, we can only publish open access if someone is prepared to pay the publishers. That’s fine for people with fancy research grants, but not an option for everyone. Some universities will cough up, but only sometimes. Until we take control of the academic publishing world and run it ourselves, open access remains a problem, The new LSE Press is a good step forward here.