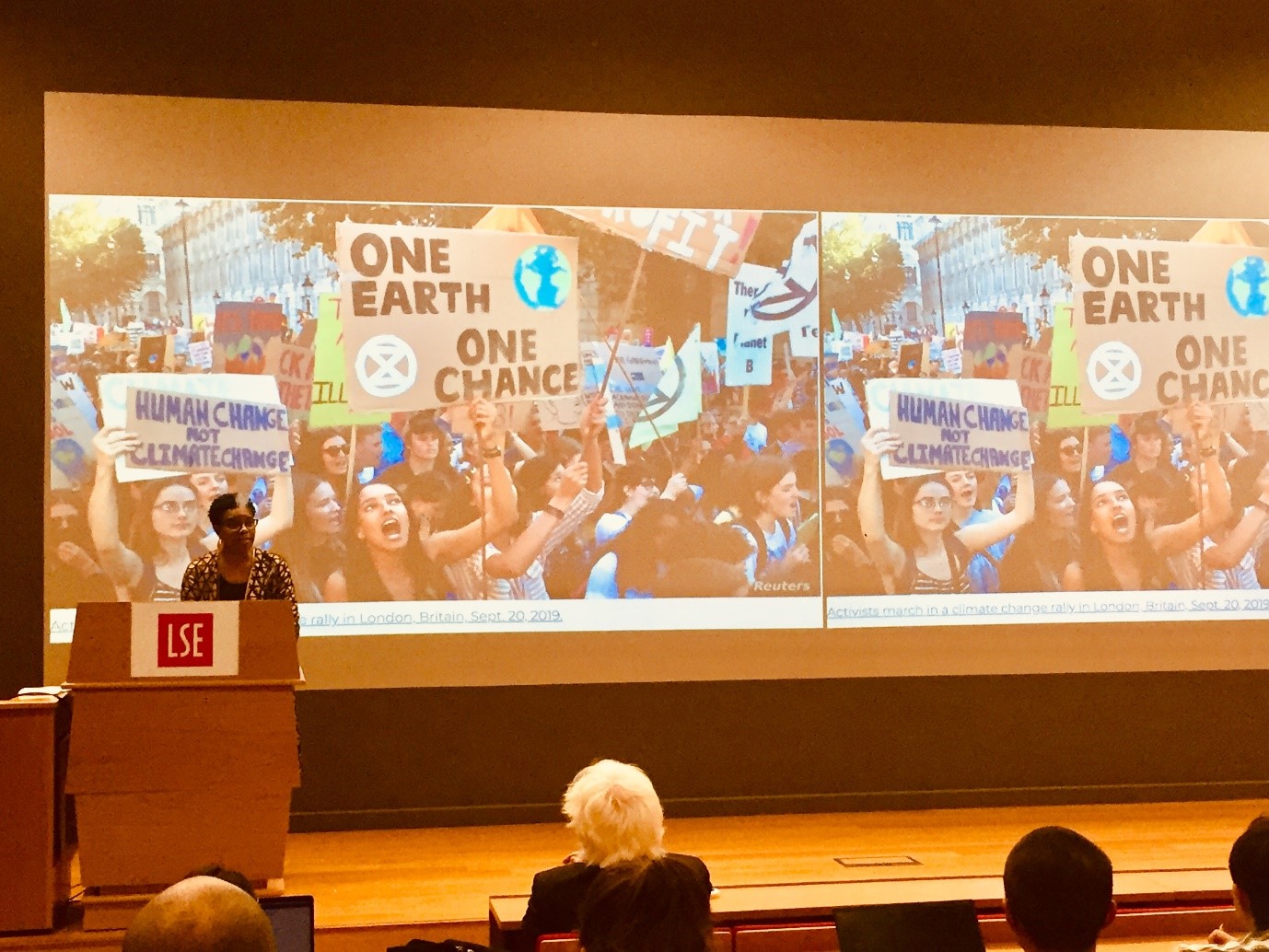

On Friday 26 November, Ingrid Srinath gave an online lecture on ‘COVID-19, Corporatisation and Closing Space: The Triple Threat to Civil Society in India’ as part of the Cutting Edge Issues in Development Lecture Series for 2021/22. Ingrid Srinath is the Founder Director of the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy (CSIP) at Ashoka University. LSE ID’s Professor David Lewis was an invited discussant for the lecture. Read what MSc students Ananya Radhakrishnan, Krithika Rao, Muskaan Arora and Bhuvan Majmudar took away from the lecture below.

You can watch the lecture back on YouTube or listen to the podcast.

The lecture was aired on the day India celebrated its 72nd ‘Constitution Day’. Ingrid Srinath highlighted the paradox by pointing out the rapidly backsliding democracy in India, indicated by the 2021 report on the Global State of Democracy. The Covid-19 pandemic, increasing state control of the market and civil societies, assaults on minorities, activists, artists, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) has invoked an extensive discourse across the world on the growing right-wing populism and autocracy in India. The way the government handled the pandemic that saw an insurmountable death rate has been widely recorded and criticised. However, the role the state played in restricting civil society in information and humanitarian assistance has not been acknowledged.

Ingrid, stressing upon the alarming rate at which civil society is being stifled, raised critical arguments on the deliberate attempt by the state in the closing of space for activists and NGOs, through brazenly bypassing the democratic procedures to pass laws, imposing arbitrary restrictions, and moulding internet and data laws to suit their needs.

“India is moving down the slippery slope of majoritarianism and authoritarianism” she says. It is widely known that we are increasingly witnessing amendments being made to the existing laws through unconstitutional means. Abolition of Article 370, amendment to the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA), Citizenship Amendment Act, being some prime examples. FCRA, originally drawn with an intent to prevent foreign influence in politics, is now being used as a weapon against civil society organisations. She points out that activists have been constantly threatened with the cancellation of their FCRA, and further restrictions were put on NGOs for receiving oxygen and ventilators from foreign nationals during the pandemic.

While I mostly agree with her remarks on the state acting against civil society such as the internet shutdown in Kashmir, law and order acting against civil society members, and arrests of activists and artists on the charges of sedition, I feel that the arguments were overtly partial, and a data-driven analysis would have provided a more comprehensive view of the changes in the civil society landscape in India.

I believe that while there has been a rise in acts of violence against a selected group of society, the issue underlying the structural and systemic disengagement and disharmony from both sides of the political spectrum have to be addressed by civil societies and academics. It is a widely known fact now, that the government, with the right populism in India, is increasingly using the internet and severely harsh laws to target artists, minorities and activists, but, there also is a growing rise in the left-wing populism selectively acting on critical issues such as with the farm laws and privatisation policies.

While Ingrid highlighted several issues, I found her perspective on the corporatisation of India’s civil society to be particularly fascinating. She critiques Section 135 of the Indian Companies Act, popularly referred to as the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) law. Under the ambit of this law, companies of a certain size are mandated to contribute 2% of their net profits to social impact causes. This certainly appears to be a step in the right direction, doesn’t it?

Well, according to Ingrid, the impact of the CSR law on civil society and philanthropy has been rather interesting. She stated that although the law has managed to reel in over double the absolute volume of corporate philanthropy, it is designed to prioritise ‘short-term, easy to measure, employee pleasing programs’, over long term complex issues that plague the country. Ingrid argued that the law has also resulted in a shift in agency, with the corporate sector repositioned as the main protagonist, leaving the NGOs side-lined as mere implementing agencies. The resulting market orientation of the social sector has accelerated preferences for ‘business-people’ on boards and leadership positions in these NGOs. She also questioned the prioritisation of social issues as a result of this marketisation, citing examples of the emphasis laid on certain policies like microcredit and other forms of financial inclusion, rather than dealing with entrenched caste and gender discrimination issues. Ingrid posited that this kind of large-scale corporatisation divides the sector into ‘good NGOs’, and the ‘black sheep’, that are to be eliminated.

Although I acknowledge the merit of some of the claims made here, I must admit I found parts of the narrative to be reductive and quite vague, painting an excessively bleak picture of India’s civil society, and downplaying the good work done by various CSR initiatives. While Ingrid’s alternative perspective on the impact of the CSR law was indeed thought-provoking, I believe a data-driven approach would have made her arguments more compelling.

Lastly, I was intrigued by the brief mention of India’s recently proposed social stock exchange. Although it does define social impact rather narrowly, its potential in attracting new pools of capital whilst raising transparency and credibility within the social enterprise sector, is indeed something to keep an eye out for.

India has very large developmental and social challenges to address. As accurately stated by Ingrid, the need of the hour is urgent reform within the regulatory framework of India’s social sector. There must be a comprehensive and transparent system of self-regulation, with an independent regulatory body.

Krithika Rao & Ananya Radhakrishnan

_______________

Civil society organisations have a key role to play in the overall developmental landscape of any country, especially so in countries that face critical challenges relating to poverty, healthcare, education, and other indicators of development. Playing a complementary role to the state, while diverging from markets, civil society organisations (CSOs) in India have extensive grassroots networks, which work to disseminate information, and provide goods and services related to social welfare. What does a threat to civil society entail for the present and the future of a nation? Ingrid Srinath, in her talk, illustrates vividly the multiple mechanisms through which the state has systematically been impeding the freedoms of civil society organisations.

Ingrid Srinath, who is currently the Director of the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy at Ashoka University, talks in detail about how the majoritarian-led nationalist government has resulted in a growing need and shrinking space of civil society organisations in India, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. From the arrests of advocates, public intellectuals, professors and even poets on flimsy grounds by castigating any form of dissent as anti-national to resorting to mere symbolism in the face of a national crisis, the sad state of Indian democracy is no less than an Orwellian dystopia.

A life-long tribal land rights activist, Fr. Stan Swamy, to a linguist professor in Delhi University, Hany Babu, the news of extra-judicial killings and framing of public intellectuals under draconian laws come with zero accountability and justification of any kind. This added with the absolute collapse of health infrastructure and lack of state response, especially during the second wave of the pandemic, evoked a need for a stronger civil society network. “Numerous individuals and groups have once again proved that when governments falter, civil society steps in to create self-help organisations that reach out to people who have been held hostage to a malevolent fate” (Chandhoke, 2021).

The response of civil society organisations combined with efforts of ordinary citizens in forms of social media toolkits with details of hospital beds, oxygen availability, contact details of oxygen suppliers, and even cremation grounds, was the last resort when the existing healthcare system was crumbling, especially in the second wave of Covid-19. What would have happened in the absence of such a strong involvement of CSOs in mitigating the COVID-19 crisis, when the state failed to step in, is a question best left unanswered. The events that have unfolded in India in recent years reaffirm Ingrid Srinath’s arguments about the threats facing civil society in India today.

In discussing a constructive way forward for CSOs in India, Srinath talks about a three-pronged approach: a reformative framework for CSOs that adheres to the values of the Indian constitution and the international treaties; repealing of century-old draconian laws (such as the Unlawful Activities Act 1967 and National Security Act 1980), and accountability of the government for the safety of humanitarian grassroots workers.

Despite the expanding need for CSOs in democracies like India, there certainly are concerns regarding the functioning and funding of these organisations which need to be addressed and cannot simply be overlooked.

It is certain that the dystopian reality of nation-states like India needs a stronger presence of civil societies while working on the reformation of the same and understanding them as complex networks working under multi-layered systems. The strong influence of CSOs and their consistent efforts in serving marginal communities have been instrumental in the realisation of several government schemes and relief programs. Despite several hurdles in the past few years, we have seen a growing rise in people’s awareness of these issues and the mobilisation of resources towards affected communities. Harnessing the wide network and impact of social media, people’s movements have gained mass popularity and following and have led to several satellite protests across the country. More so, acts of CSO repression have sparked the much-needed debate about how and in what ways do civil society organisations impact developmental outcomes and why the CSO space is in dire need of global attention.

Bhuvan Majmudar & Muskaan Arora

_______________

The next guest lecture will be with Terhas Clark and Mosharraf Hossain on Friday 3 December 2021 on ‘Disability, Development, Rights and Inclusion’. LSE Students, Staff and Alumni can register here. External audiences can join the lecture via YouTube.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.