PhD candidate in the Department of International Development Jorich Johann Loubser analyzes the 2022 World Inequality Report, recently published by the World Inequality Lab, and asks whether implementing tax reforms without curbing rampant financialization can tackle global inequality.

Last week, the World Inequality Lab led by Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, released the 2022 World Inequality Report. The yearly report comes after significant empirical work, which has culminated in what is probably the widest and strongest collection of historical and contemporary data on income and wealth inequality available. Having read the 236-page report, this blog post serves as a summary of the main points of the report, and what I believe we should take from it. All the figures included below are from the report.

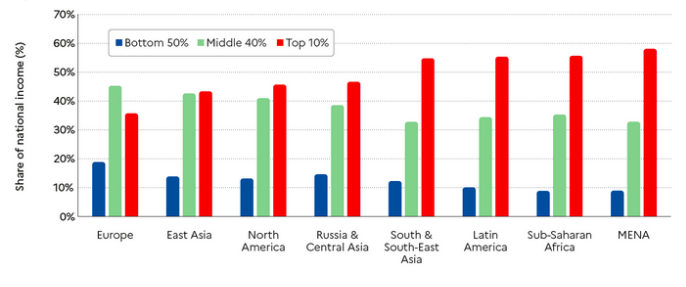

The report continues the lab’s emphasis of shifting away from the use of the Gini coefficient as the primary indicator of inequality.1 Instead, the report places emphasis of the distribution of wealth and income across three national level groups, the ‘bottom 50%’, ‘middle 40%’ and the ‘top 10%’. Across both indicators of wealth and income, the report illustrates that inequality has risen significantly since the 1980s – and continues to rise. Figure 1 presents income inequality across different regions (MENA stands for the Middle East and North Africa). While intra-country inequality has risen everywhere, some areas (particularly the last three regions) are significantly more unequal than others.

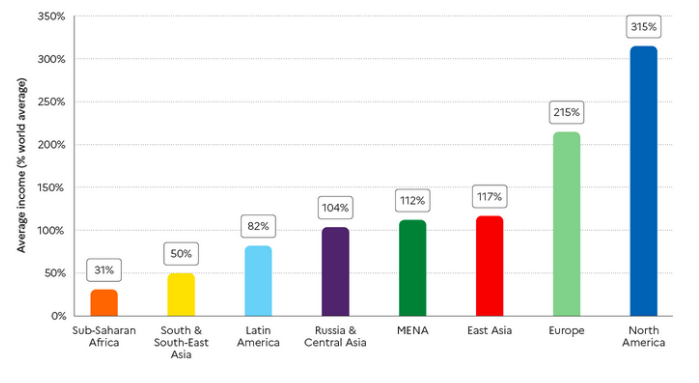

Between-country inequality has declined since the 1980s, largely due to the tremendous growth of the Chinese economy. However, many previously poorer regions continue to lag behind. Figure 2, which presents average incomes across regions as a percentage of the world average, shows that the average income in Sub-Saharan Africa is only 31% of the world average. Thus, while growth across Asia is shifting the distribution of economic benefits globally, many areas remain excluded from this process.

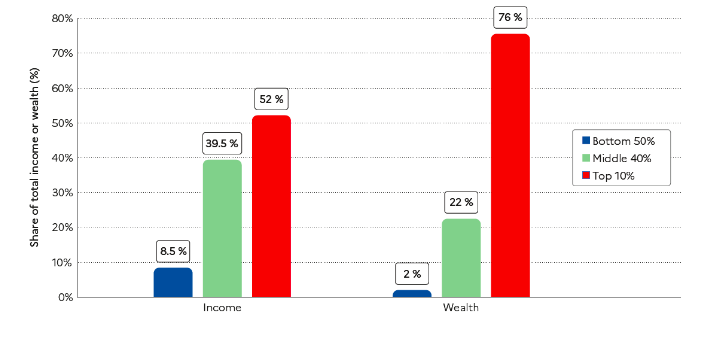

If income inequality was itself not bad enough, the report finds that wealth is more unevenly distributed than income – see figure 3. Wealth inequality of course exacerbates income inequality, as individuals are able to earn future income on current wealth.

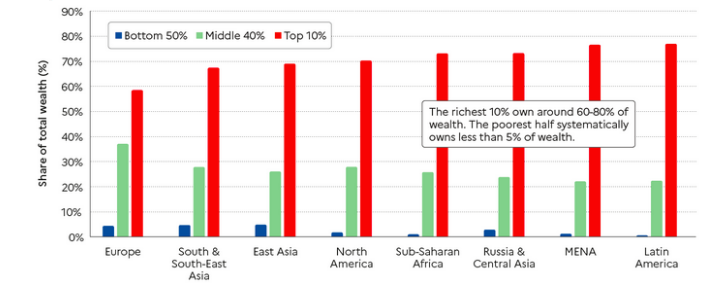

While wealth inequality varies significantly across regions as figure 4 indicates, it is clear the top 10% are the dominant wealth holders globally, with the bottom half of the world owning less than 5% of wealth. The report dates the emergence of the current upward trend in inequality to the 1980s – a period marked by significant privatisation, deregulation, liberalization of trade and financial markets and significant tax reductions.

These reforms have allowed a concentrated elite to accumulate the largest component of the wealth generated. Figure 5 depicts the average annual wealth growth rate across wealth groups between 1995 and 2021. It shows that an ever-increasing elite minority are acquiring an ever-increasing share of economic benefits.

The report, along with a wide array of scholarship, argues that one of the dominant drivers of the above dynamics has been financialization – which describes both the relative increase in the size of the financial sector and the increasing reach of finance into other sectors. This has in turn seen an increase in the share of financial assets in total wealth held by private individuals.

Despite the importance of wealth and income derived from financial assets, the report illustrates that the gains made from financial incomes (as well as most income accumulated by the top 10%,) and smaller elite groups within that, remain been insufficiently taxed – they stress that income tax for the elite and corporate tax have declined significantly in many countries. In particular, the authors stress that while income tax has taken on a progressive structure, most wealth taxes have been charged at a flat rate. Similarly, wealth tax has often been confined to property and not other forms of wealth – such as the above financial assets.

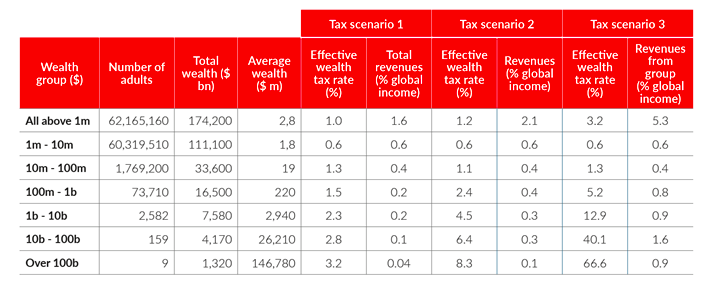

In response, the authors call for higher income tax rates globally. However, one of the principal solutions the report offers is a global wealth tax. The proposed wealth tax is progressive and will be aimed at those whose wealth exceeds US$1 million. They provide three different scenarios with different effective tax rates – presented in table 1 below. The simulations account for losses due to tax evasion. They also provide a tool which allows users to develop their own simulations.

In the first simulation an effective wealth tax of 1% would raise revenue equivalent to 1.6% of global income. While in the third scenario, which is more aggressive but by no means a socialist revolution, an effective tax rate of 3.2% would raise 5.3% of global income in revenue. In the third scenario, tax “rates reach 50% over $10 billion and 90% over $100 billion. This would in effect ban wealth accumulation over $10 billion” (p.140). The authors admit that this reform would require significant global cooperation but is possible if spearheaded by sufficient political will.

The scope of the report is fantastic (and generally very accessible), and the solutions they offer are key tools in the fight against inequality and poverty globally. However, readers should not be lulled into seeing increasing tax rates and the ensuing expansion of redistributory policies as a silver bullet. They are clearly important, but they are but one step in this generational battle.

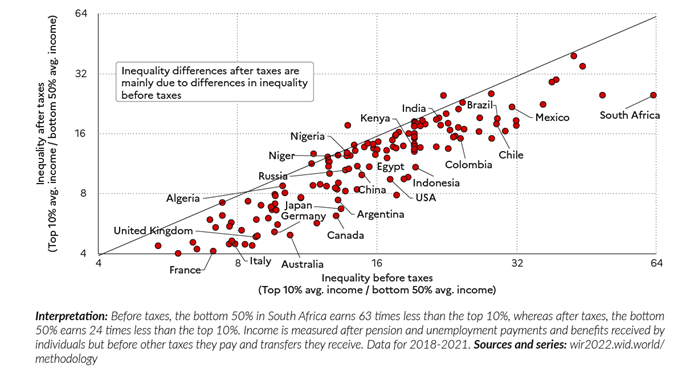

When reporting on income the report generally looks at pre-tax income, which does not take into account taxes and redistributory transfers. Generally, including these figures changes very little regarding the overall global picture. Figure 6 depicts the ratio of income earned by the top 10% in relation to the top 50% pre-and-post tax and supports this. However, one must note that South Africa is clearly an outlier, with the ratio more than halving when taking into account tax and government transfers.

As I have argued before, while South Africa remains one of the most unequal countries in the world, it is not because the state has not attempted to address this. The country has a highly progressive tax system, extensive welfare access and comparatively very strong unions. The report argues that South Africa’s inequality stems from a lack of structural reforms “including land, tax and social security reforms” (p227). This understanding of South Africa’s inequality is incomplete. The high level of income inequality is driven largely by the fact that finance is the largest sector in the economy, accounting for 20% of GDP in a country where the unemployment rate is an astonishing 34.4% (along the strict definition). South Africa is a signal to the world of the dangers of financialization, but it also provides evidence that tax reform, while critical, is insufficient.

The report draws much-needed attention to the importance of fiscal changes. However, to adequately address inequality states must actively address burgeoning financial capital – something which tax reforms are unlikely to adequately address.

Long-term reform projects must be aided by supportive intellectual scaffolding if they are to be successful. The 2022 World Inequality report provides a highly accessible account of how we got here. Additionally, it offers strong evidence that addressing income and wealth inequality will require extensive tax reforms. However, this is not enough. The extreme decoupling of the real economy from financial markets witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic – where production dropped as economies shrunk during the pandemic, but stock markets grew significantly – is but one of the recent examples of the dangers of financialization. Effective reform will require fiscal changes, but we must get ready for a battle with financial capital if we are to create better economies.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photo Credit: London’s Financial District via Reuters.