MSc student in International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies Courtney Bateman shares a reflection on a recent trip to Cumberland Lodge in January 2022 which focused on addressing contemporary humanitarian challenges.

Leading up to the event, it all felt very “school trip.” We packed our overnight bags, waited for the bus to come pick us up at our designated meeting spot; excited and nervous anticipation hung in the air as we wondered who we would be sharing a room with, what the itinerary meant and what exactly we would be served for our meals (would it be cafeteria food or food food?). We knew the words “Cumberland Lodge” and something about simulations was mentioned to us repeatedly. At 14:45 sharp on Friday 21 January, we piled up our luggage, loaded on to a bus, and were on our way to the English countryside.

Soon, we came to more fully realize just what this “school trip” would entail. In one sense, some of it did feel like a weekend away with friends, complete with morning yoga, ABBA karaoke, and vegetarian dining (turns out the food, prepared by a British Algerian chef, was impeccable and anything but your typical cafeteria cuisine). In another sense, however, our weekend away was nothing like anything I’d ever experienced before.

Firstly, we had the absolute pleasure of having our sessions led by Sir Mark Lowcock, former head of the United Nations Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). On our very first evening, we had an informal, fireside chat chaired by Professor Stuart Gordon, where we were able to ask Sir Mark our most pressing questions about humanitarian work, the nature of it in practice, and some of the key take-aways he learned from a role as important and prestigious as the one he held for four years. We were all furiously scribbling notes as he imparted his wisdom; something I especially took away from that night was the importance of remembering who humanitarian work is for. In the projects we have been associated with, and will be associated with in the future – are we really stopping to consider the humanity of those we are hoping to serve? As this weekend was focused on humanitarian disasters and refugee work, he asked us pressing questions such as: do we view all refugees as a homogenous block? Do we assume they all want and need the same things, in different situations or even all within the same situation? When we do this work, are we really acting on behalf of the people affected, or do we have ulterior motives? This was a powerful wake-up call to remind us not only the who behind our work, but the why. It was so insightful to have him on board, not just for that first evening, but to provide thoughts and advice on our activities throughout the weekend.

On Saturday and Sunday, the mysterious “simulations” began. Professor Gordon led us in a debriefing, outlining a scenario of a made-up African country at war and the neighboring country receiving those displaced due to the conflict. We were broken into teams and all given roles and background information on those roles – motivations, concerns, and other important details. These ranged from high-ranking officials like UNHCR leaders, the African Union, national government representatives, to more lowly positions such as regional leaders and spokespeople, “concerned citizens,” and refugees themselves; in short, anyone who would have some skin in the game regarding a crisis of this size in real life. The simulation was to put them all around the same table to discuss what should be done about the crisis at hand. People assumed the roles of their characters and brought up concerns that they supposed that character would have. Border control was concerned about national security and the maintenance of it. Citizens worried about jobs, their towns getting overrun, why refugees were receiving funding but not themselves when they also were struggling. UNHCR wanted to spare no expense to help the refugees, but who would take on the funding? UN OCHA, as inspired by Mr. Lowcock, wondered how we could get to the heart of the conflict; can we put our efforts into solving the problem itself, rather than merely addressing the symptoms? At one point, there was even a refugee revolt where they took to the “media” to express their anger at not feeling heard and attended to. This simulation helped us to realize what sort of conversations take place around each humanitarian event, what arguments might come up, and how we can keep the humanity of refugees at the heart of this important work.

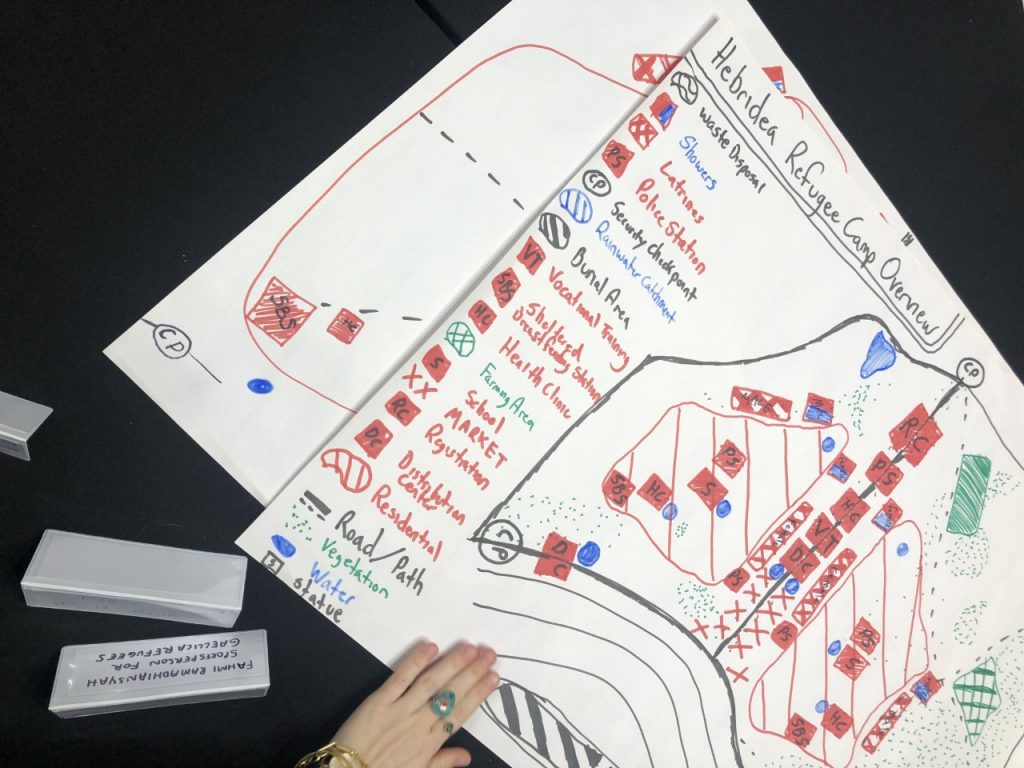

Sunday brought a whole new simulation. We trekked out to the great Windsor Park (and spotted lots of deer, dogs on walks, and a castle in the distance!) to scope out the location of a “new refugee camp” we would be constructing. Again, we divided into teams to see who could come up with the “best” solution for the refugees that would soon be arriving in the area. Throughout the discussions, “actors” pretending to be anything from funding sources, distressed refugees, even IKEA pitching their temporary housing structures would interrupt and demand attention. The meetings quickly became chaotic, with attention being pulled every which way, as everything felt like a pressing concern that needed to be addressed now (“I just saw someone get stabbed!”, “USAID waits for no one!” Etc.) Through all of this, the camp designers had to keep so many things in mind: the safety of the individuals, the complex dynamics between ethnic groups, were latrines going to run into fresh water sources, and so much more. We know the importance of some things instinctively through the courses we undertake in our degree –women need special protections, children need to be educated, sturdy shelters are preferable to tents or lean-tos. But where is the money and support coming from? What is the highest priority when refugees are already arriving and you are still planning? How do you prioritize the many different needs within a diverse group of refugees? As we discussed our ideas with Professors Lowcock and Gordon, we felt again how important this work is, but also how difficult it is. There are so many moving parts, so many things we would not have even thought of unless we had been shown the intricacies through these simulations.

While this learning experience was invaluable, perhaps the part that I loved the most was simply all the students who showed up. There were over 40 of us in attendance. We all took the time out of our lives and busy schedules. We all paid to spend time away from home and park our schoolwork, to participate in these learning simulations. What I saw, what I was able to observe and participate in quite clearly this weekend, was 40 young, passionate individuals who care; who are dedicated and driven to helping the earth and the people on it, in whatever we they can. We were offered a weekend away where we could learn a little bit more about how to be more ethical, more sustainable, to be humanitarians in a better way, and we jumped at the chance. The entire weekend, I was filled with the coolest, most indescribable feeling that we are the future. Perhaps more than anything, what this weekend away at the Cumberland Lodge gave me was hope. When the future of the world is in the hands of people who care so deeply and genuinely, then it is bound to become a little better.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photos: Courtney Bateman

Great article detailing an invaluable experience from those who have actually been in the midst of the challenging job of organizing the humanitarian crises of people you eventually will serve. Real world problems, real world challenges to overcome, plan, anticipate and resolve. What an incredible educational experience from such highly qualified experts. You really are our future leaders in such circumstances. Thank you for the insightful article. I have a much greater understanding of what all of you could be doing in the years to come to help those who need it most.