MSc student in Health and International Development Alya Akbar pays tribute to the late Paul Farmer and his immense contribution to the field of global health.

As a Health and International Development student, news of the sudden passing of Paul Farmer was deeply saddening. A physician, anthropologist and humanitarian, Paul Farmer was an esteemed figure who wrote spiritedly about issues of structural violence wherein the most marginalized groups are predisposed to certain illnesses. He dedicated his life to working in resource-poor settings to provide comprehensive healthcare services to the world’s poorest people. In his honour, I have abridged some of the ideas which future global health practitioners should continue to uphold if we are ever to bend the arc of the moral universe towards justice, to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr.

Among his various attainments, Paul Farmer was a professor at the Harvard Medical School, author of multiple global health books, and co-founder of Partners in Health, a social justice organization that aims to provide health services globally Through his ethnographic and anthropological writing, he amplifies the voices of the poor whose stories serve as testaments to the structurally embedded inequalities that cause poor health outcomes. In these powerful, eloquently narrated stories, he elucidates the ways in which racism, gender or socioeconomic inequalities are paralleled in the pathologies people are afflicted with. Farmer explored this concept in his 2003 publication, Pathologies of Power, and the same trend prevails 17 years later in a pandemic where marginalized groups have borne the greatest brunt of severe illness and inaccessibility to vaccines. As Farmer identified and as we continue to witness in the pandemic, the distribution of illness is not merely biologically determined. It is influenced by broader socio-cultural and politico-economic factors, and by the uneven distribution of wealth and power.

The rich discursive contribution Paul Farmer made to the field of global health is emblematized in the organization he co-founded, Partners in Health (PIH). Recognizing the inherent dignity of every individual and giving greater credence to local knowledge and understanding of disease, PIH’s strategy of ‘accompaniment’ prioritizes walking arm in arm with the poor, rather than leading them. The model stresses values of partnership, people-centred care, and the importance of listening to the needs of the people we serve. It involves “accompanying the sick and the poor and sticking with the task until it is deemed completed not by the accompagnateur but by those being accompanied”. It is both a medical and moral mission, stressing the importance of solidarity and partnership in efforts to improve global health. To this end, Farmer advocated for a value of equality not just in the distribution of health services but also in our roles as health and development practitioners.

In my favourite of his books, Reimagining Global Health (2013), Paul Farmer outlines his vision of health as a human right. He argues that the struggle to provide care is linked to the struggle to adequately conceptualize and practically implement health as a universal human right. Though health is formally recognized as a human right, this conceptualization is inadequately supplemented by both national and international legislations. A market-based, consumerist and capitalist model of care still prevails across much of the world whereby the insecurities of poor groups are capitalized upon by powerful actors. What Farmer aimed to convey throughout his work is that medical apartheid and injustice are not intrinsic or natural but are a result of violent structures and systemic forces which perpetuate inequalities.

He instilled in me a belief that a vision of health as a human right is not a chimera nor an impossibility, but a practicable reality if we work towards it strategically. He illustrates the versatility and wide range of a reimagined global health movement in which anyone from any background can take part. He said: “These are human problems, and the ability to engage with them is not limited to those with certificates of advanced training.” To this end, he proposed a feasible guide to a successful global health initiative which involves:

- A thorough understanding of key global health issues

- Starting a dialogue with policymakers

- Highlighting key issues and advocating their visibility

- Organizing public demonstrations to hold key actors accountable for their responses

- Building a coalition through reaching out to peers

- Being the change by listening before speaking and creating genuine solidarity around a cause

To conclude, Farmer wanted health inequalities to be understood not as natural, but as products of violent systems and structures. He stressed accompanying the poor and listening to their needs to create people-centred care systems. He wanted health to be reimagined as a human right everyone has access to rather than a luxury that few could afford. Finally, he reimagined a future which would amplify the voices of the bottom billion, challenge power structures, and align with a rights-based approach to global health. In his honour and memory, we should take heed of this advice and engage in global health in ways that are meaningful to those most affected by health issues and least represented in their solutions.

Citing the words of Marco Caceres, he presented a quote that fuels my reimagined vision of global health: “Every storm must begin with a single drop of rain. And so it is with every worthwhile movement…it begins with an idea that is too simple to be taken seriously…and then comes the storm.”

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

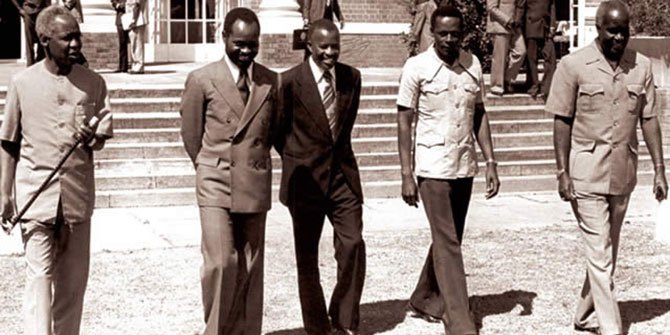

Image credit: Direct Relief on Flickr.

A great read! Mr. Farmer will be truly missed!

Great tribute to a giant and a life well-lived.