LSE Fellow and Co-Director of the International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies programme Dr Ian Madison looks at examples of non-violent resistance from previous conflicts around the world and questions whether insurgency is the only way to resist occupation in Ukraine.

Picture this: a convoy of Russian military vehicles happens upon a crossroad on the way to Kyiv. Helpfully, a large road sign provides direction. Continue straight? “F—k off”, it reads. Perhaps turn left? “F—k off, again”. Okay, hang a right? “F—k off back to Russia”.

These road signs do not exist—at least not yet. But a photoshopped image of one has been posted on social media by the Ukrainian highway authority along with a message urging Ukrainians to remove or alter road signs to confuse Russian troops. There is evidence that the call has been heeded. Road signs are disappearing across the country.

Small acts of civilian resistance have proliferated across Ukraine since Russian troops invaded. Videos circulating around social media or online news sites show innumerable instances of individual courage in the face of overwhelming military might. Seven days in, Putin’s apparent calculation that Ukrainian soldiers and civilians would give up the fight seems badly misjudged. A growing consensus of Western commentators now exhort Ukrainians to “give Putin a bloody nose”. Ukrainians are doing just this. Putin’s taking of Ukraine no longer seems a forgone conclusion.

Still, large areas of the country are already under occupation. More may follow. Yet even if Putin takes Ukraine, holding it is a very different matter. To make that task difficult, many observers want more than seemingly insignificant small acts. As videos circulate of recipes for Molotov Cocktails, Western analysts see prospects for a violent insurgency. One former CIA official, now at a think-tank, wonders whether Ukraine could become ‘Putin’s Afghanistan’. Over one million Afghans died during the Soviet occupation, five million became refugees, and millions more were internally displaced. “But they won,” he says, wondering: “Are Ukrainians prepared to pay the price?”

Make no mistake, that “price” is a euphemism for shattered dreams, bereaved families, and unimaginable suffering. A growing body of empirical research shows that there may be an alternative way to fight occupation: non-violent resistance.

The concept has a long lineage. From Henry David Theroux, Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, most saw non-violence as a powerful moral principle. In contrast, Gene Sharp—perhaps the most influential theorist of non-violent action—argued that it could be effective on a purely instrumental level. The power of any state, Sharp argued, is not a matter of coercive capacity, as Clausewitz or Machiavelli might have it. Nor is it a pinnacle to be captured, as Marxist theorists would argue. For Sharp, the heart of political power is a question of obedience. When enough people withdraw that obedience, states tremble.

The fluffy reputation of non-violence belies a solid empirical foundation. In an exhaustive study, Erica Chenoworth and Maria Stephan note that over the past century non-violent campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success when compared to violent counterparts. For anti-regime campaigns, such as the recent revolution in Sudan, they are far more effective. When it comes to anti-occupation—the scenario facing Ukrainians—the two methods are matched, but violent insurgencies lasted longer, came with enormous costs in human lives and infrastructure, held lower probabilities of building democracy afterwards, and often traumatized civil society in the process. This is the flip side of becoming ‘Putin’s Afghanistan’.

What makes non-violent resistance so effective is popular appeal. For most people, taking part in street marches, strikes, and sit-ins is far less costly than picking up a gun. The more people participate, the higher the costs for the occupying power; eventually, though not inevitably, key supporters of the regime begin to falter. How can non-violence work in practice? Gandhi outlined eight steps, ranging from agitation to non-cooperation and ultimately setting up parallel political structures. Gene Sharp goes even further, listing a total of 198 options. The key point is that resistance falls on a spectrum. Actions are tailored to the context and escalate as necessary.

Not all non-violent campaigns succeed. But even ‘failures’ hold lessons. One example, the subject of my PhD research, was a campaign in Kosovo during the 1990s. Spurred on by Slobodan Milosevic’s discriminatory policies against ethnic Albanians, a local literary theorist named Ibrahim Rugova—the “Gandhi of the Balkans”—oversaw a comprehensive disobedience campaign against the Serbian state. Strikes and protest marches morphed into an entirely separate, avowedly non-violent, parallel system. Parents sent their children to underground classrooms in basements, Mosques, churches, and disused factories to avoid using Serbian-run schools. Thousands of babies were delivered in hidden clinics. Sustained by voluntary taxation and diaspora contributions, the campaign lasted for almost a decade. And yet, Milosevic—like Putin, an isolated, paranoid leader driven by irredentist nationalism—did not budge. In the end it took a violent insurgency and an intervention from NATO for the campaign’s aims to be achieved. The latter is untenable for Ukraine. Milosevic did not have nuclear weapons.

What accounts for this ‘failure’? Several factors are important, but a crucial issue was the lack of international action. Rugova waited for the ‘good behaviour’ of non-violence to be recognized by Western states. Yet for the West, Rugova was effectively containing the situation. Violent outrages in Bosnia and Croatia eclipsed the troubled, yet quiet province. Kosovo was just not bad enough.

The challenge for any similar campaign in Ukraine is to maintain international focus on the fundamental injustice and lack of popular acceptance to Putin’s rule. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s savvy use of social media, not to mention the hundreds of stories and videos already circulating, are an important aspect of this. Yet indications are that this will be a long war, and possibly a much longer occupation. Pressure must be sustained, even if a bloody insurgency does not come to pass.

Changing road signs may seem inconsequential. But if we take Gene Sharp’s point that power is ultimately a question of obedience, not something that “grows out of the barrel of a gun”, even small acts of resistance can yield results. In the meantime, we can all endeavour to mitigate the suffering that the invasion has already wrought.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

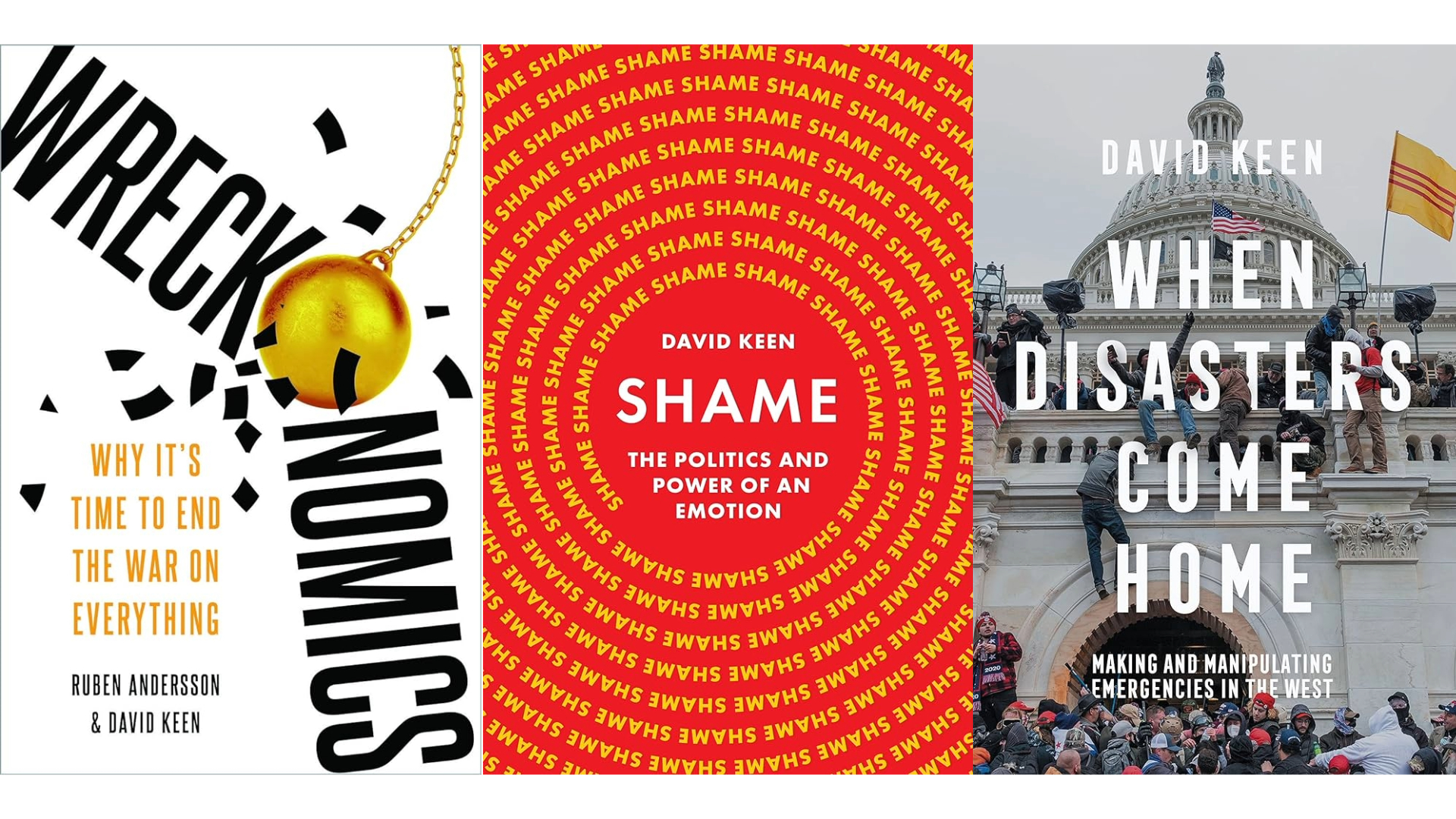

Image credit: Modern War Institute.

You can read more from LSE Experts on the situation in Ukraine here: https://www.lse.ac.uk/Research/ukraine-lse-research-and-commentary.

A truly insightful article with a for me very novel way of dealing with this awful situation.

Hi Ian! Appreciate you bringing the research around the power of non-violence to this question Ian. Not many are doing that in these dark weeks. When there is so much violence already with Russia’s brutal invasion it is hard to imagine how to use this approach but its important to keep in mind its effectiveness in the long run. I’ve also encountered some truly frightening analysis coming out of US military-strategic circles suggesting that somehow the Afghanistan model is a promising way to “help Ukraine” – that part where the CIA armed and financed the Afghan mujahideen in Pakistan in the 1980s. Boggles the mind!!!! Given the horrific cycles of factional violence that approach unleashed, including the rise of the Taliban and then the US invasion and 20 years of US – NATO military-enforced trusteeship facing a nowTaliban insurgency… let alone last August’s heartless abandonment of Afghans in the end when the cost became unsustainable…it is truly incredible that people are seriously fielding these arguments. Military solutions in divided societies end up empowering those who ruthlessly will use military force over those who prefer peace, compromise and democracy. My doctoral research also was in Kosovo (as you know) and anyone who studied Kosovo knows that many of the KLA insurgency’s commanders dominated society through violence and killings for years after the war and captured politics, the state and its assets – a situation Kosovo is finding a way out of only recently. A formal democratic system and a big US and European presence didn’t save Kosovo from that outcome. It is a matter of survival now for Ukrainians to meet violence with violence. But I hope if there is a need for a “long-run” strategy, there is a hard look at these past models and whether they prove themselves to actually secure the peace and democracy Ukrainians want and deserve.