On Friday 28 October, Branko Milanovic gave an online lecture at the LSE as part of the Cutting Edge Issues in Development lecture series on “Recent trends in global income distribution and their political implications”. Professor Milanovic, formerly a lead economist at the World Bank, focuses predominantly on income inequalities within nations and on a global scale.

Read reflections on the lecture written by Mihika Dutta, Ramya Prabhakaran, Catharina Schaufler-Mendez, Kshitanjay Sondhi and Angeliki Tzampazi.

“The past always counts [because] the inequality of the world is the result of the structural realities at once slow to take shape and slow to fade away”; this quote by Fernand Braudel, the opening slide to Branko Milanovic’s lecture at LSE, is an important reminder to not turn a deaf ear to the history that shaped the world we see today.

The famous ‘Elephant curve’, coined by Branko Milanovic himself along with Christoph Lakner, depicts the real income growth observed at different percentiles of the global income distribution. It is representative of the huge differences in inequalities during the period 1988-2008. The exponential rise in real incomes for the 99th percentile while the bottom 5th percentile remained almost stagnant is indicative of income disparity. Post-2008 Financial Crisis, the Elephant curve has changed, but the underlying mechanisms remain the same. Rapid growth in China left an “empty spot” at the bottom quintile which was filled by India, a phenomenon called the “sucking below” effect.

Shedding light on the lessons from the past few years, exogenous shocks seen worldwide must not be overlooked to understand the greatest setbacks to global poverty and inequality reduction today. These are the aftermaths of COVID-19 pandemic, US-China trade war and Russia-Ukraine war.

As we turn our attention to today’s context, relative inequality is falling in the developing world. This is interesting to observe in the COVID-19 context, where the implementation of expansionary fiscal policies by governments in developing countries are helping to drive this change. As Professor Francisco Ferreira, the discussant of the lecture mentions, while GDP was largely falling during COVID, household incomes were increasing due to governments adopting measures such as cash transfers to soften the impact of COVID-19 on their populations. Professor Ferreira also brought up a crucial aspect of working with inequality. In his opinion, we should emphasise the range rather than the levels of inequality.

Upon being asked about the solutions to tackle global inequality challenges, Branko Milanovic points to the government interventions utilised during the two years of COVID-19, explaining how these have demonstrated that we already know how we can create change in global inequality. However, achieving this in the long term will ultimately come down to the political appetite to implement and carry forward such initiatives in the future.

– Mihika Dutta and Ramya Prabhakaran

________________________________

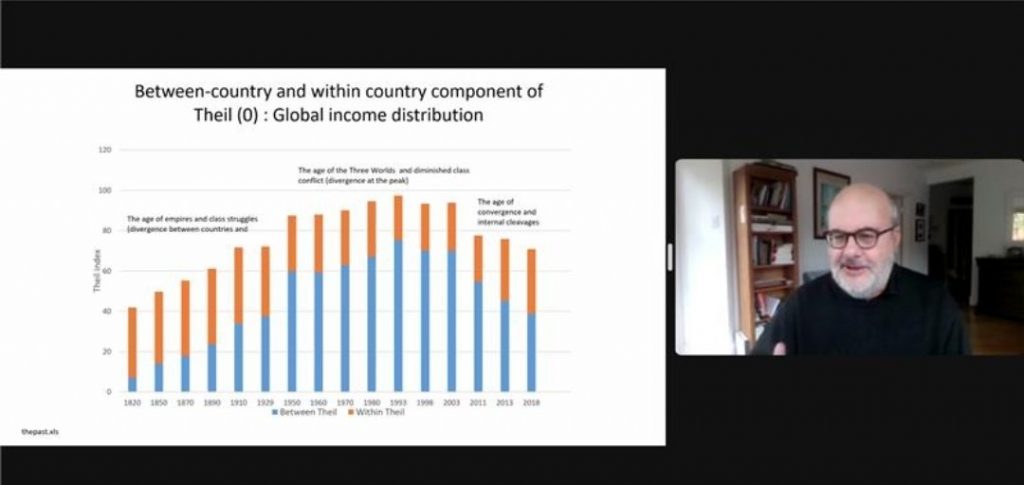

Milanovic starts his lecture by outlining global income inequality as a result of long-standing structural issues, providing historical data and context from 1820 to 2018 and showing the changes in Gini indices (measurements of inequality within an economy). Then he delves into various eras and certain countries specifically, such as the US, whose GDP flourished during and after WWII, and China, whose inequalities increased dramatically during that same time. He also highlights the similarities and differences between the previous rise of Western nations as global powerhouses vs the rise of Asian powerhouses, with the former increasing global inequality, and the latter decreasing it, as poorer nations are using it as a way to catch up.

Concluding, Milanovic delves into the most significant exogenous shocks we are currently dealing with:

- Aftermath of Covid-19: The pandemic resulted in a stark increase in inequalities within many countries that was not initially anticipated. However, when governments became involved and attempted to mitigate this rise in inequality, as was very surprisingly seen in the US under Trump’s presidency through cash transfers, inequality was lessened.

- US-China trade war: Still ongoing, it raises many questions, such as whether it will slow down China and thus global poverty reduction, as China has been a pivotal force in reducing global income inequality.

- Russia-Ukraine: This conflict will also most likely have a significant effect on global inequalities through the energy crisis it has already been causing, particularly in Europe, and the food shortages due to exporting difficulties from Ukraine.

Additionally, Milanovic highlights the importance of larger African nations as a potential replacement for the role that China has played as a mass reducer of inequalities, since the ‘China effect’ of reducing global income inequality has reached its end, with the nation having become sufficiently rich, leading to an opposite effect. Nevertheless, these are all just predictions, as Milanovic reminds us.

Like Milanovic, I believe it is absolutely vital to understand the structural causes of global inequality and the vast influence the past still has on current issues, as we will continue to face exogenous shocks, with new ones a guarantee. A focus on the globally interconnected structure of inequalities is crucial if there is any hope in understanding and dealing with global inequalities.

The future of global inequalities remains uncertain and unpredictable, yet the past does tell us a fair share.

– Catharina Schaufler-Mendez

________________________________

A famed speaker and a presenter whose work is keenly observed by students whenever he speaks, Professor Branko Milanovic is most well-known in academia as the author of several books on global inequality, capitalism, and liberalization. In his guest lecture at LSE, he shed light on the facets of inequality that we have in the status quo. The idea that the world gradually has become more unequal since times immemorial is horrific, yet mathematically convincing enough to prove. While there has been monumental growth in Asia since the 2000s, its growth trajectory is in tandem with Western counterparts. This is contrary to the incidents of the past, where Western countries observed economic growth while the Global South was impoverished. Through some evidence-based-intervention graphs, we got to know that the current global scenario houses the fact that inequalities within nation-states are also at an all-time high compared to between nation-states.

Prof. Milanovic also explains that after the financial crisis of 2008-13, there seemed to be no improvement for the western middle classes. Even in the global growth incidence curve, there were substantial observations that concluded that there has been strong and monumental economic growth at the bottom and the middle tier of the global income distribution while the topmost section suffered from low and largely disappointing growth.

In continuation of the arguments in support of Asia’s elevation globally, Professor Milanovic gave us two main terminologies:

- “Empty slots”: spaces created by China’s population upliftment and transitioning to the Indian population;

- “Sinking below” effect: Indians now comprise 40 percent of the bottom quintile of the income distribution statistics.

Discussing the contemporary and mainstream economic shocks to income distribution globally, three came forward in the eyes of the policymakers:

- COVID-19: needless to say, it led to uneven inequality and unprecedented government spending without any rehabilitation;

- US-China Trade War: the trade war has hurt the interests of the people from both spectrums leading to the shift of value chains from China and the USA both;

- Russia-Ukraine conflict: both the stakeholders have faced wrath in this, with Ukraine being destroyed and Russia facing humongous economic sanctions from the West.

As the proceedings got ahead and our discussant Professor Fransisco Ferriera got the podium, he succinctly commented about the inequalities which stemmed out of COVID-19. His quote, “the poorer you were, the higher were your income losses” can be meticulously crafted as a footnote demystifying the concept of Covid-19 and its global implications.

– Kshitanjay Sondhi

________________________________

To understand why global inequality matters, it is necessary to encapsulate the various entanglements that come along with equality of opportunities, migration, climate change and international politics, amongst others.

The stagnation of real incomes of the middle class in rich countries is the result of globalisation and rising incomes of the middle class in poorer countries. Poorer countries are catching up with richer countries and growing at a faster rate. That could mean that if someone (China) is getting ahead of someone else (US), the relative position of the latter is dropping, leading to political issues and tensions, as Branko Milanovic explained during his talk. Income disparities grow; pro-rich policies are pushed forward, resulting in plutocracy, in the case of US and populism in Europe.

The average income of the richest 10% of the population is about nine times that of the poorest 10% across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Oxfam’s ‘Time to Care’ report confirms that economists in the past disregarded the study of inequality, cared only of averages, homo economicus was the main figure and equal distribution of wealth and income were out of the table. According to Oxfam:

- The 22 richest men in the world have more wealth than all the women in Africa

- Women & girls put in 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work each and every day; a contribution to the global economy of at least $10.8 trillion a year, more than three times the size of the global tech industry

Unpaid care work is the hidden engine that keeps the wheels of economies, societies and businesses moving. Alongside the global care crisis and the ageing population, the climate crisis and high-carbon lifestyles are a burning issue. The top tier of the wealth distribution, who account for the highest emissions, has not been the focus of policies to mitigate climate change or reduce carbon. Instead, the further someone looks down the wealth distribution, the higher the percentage people pay for energy. According to World Inequality Lab, an 11-minute ride to space, like the one taken by Jeff Bezos, is responsible for more carbon per passenger than the lifetime emissions of any one of the world’s poorest billion people.

The world’s top richest people are driving global warming and their wealth and decision-making power is as impactful as nationwide policy interventions. A carbon-free lifestyle and low-emission products might sound exclusive to those who face heavy barriers from entering the middle class, as the unequal income distribution and global inequality seems to serve and benefit those sitting on the higher end of the pyramid. Thinking of the bottom of that same pyramid, whose aspirations are limited to survival, these goals of individual carbon reduction are unworkable, especially when they are suffering the disastrous effects of climate change from which the mega-rich are protected.

– Angeliki Tzampazi

The next guest lecture in the Cutting-Edge Issues in Development series will be with Naomi Hossain on Friday 11 November on “The Popular Politics of 21st Century Food and Fuel Riots“. Members of the LSE community can attend in person (contact d.patel20@lse.ac.uk for details) and the wider public can register to attend via Zoom.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main image Credit: Unemployed people waiting in front of an employment agency in Lilongwe, Malawi via the International Labour Organization on Flickr.

1 Comments