Witnessing the drastically falling fertility rate in China, Political Economy of Late Development candidate Yunqi Wang shares her interviews with three unmarried Chinese women on their opinions about recent fertility encouragement policies introduced by the Chinese government.

What happened with the fertility policy?

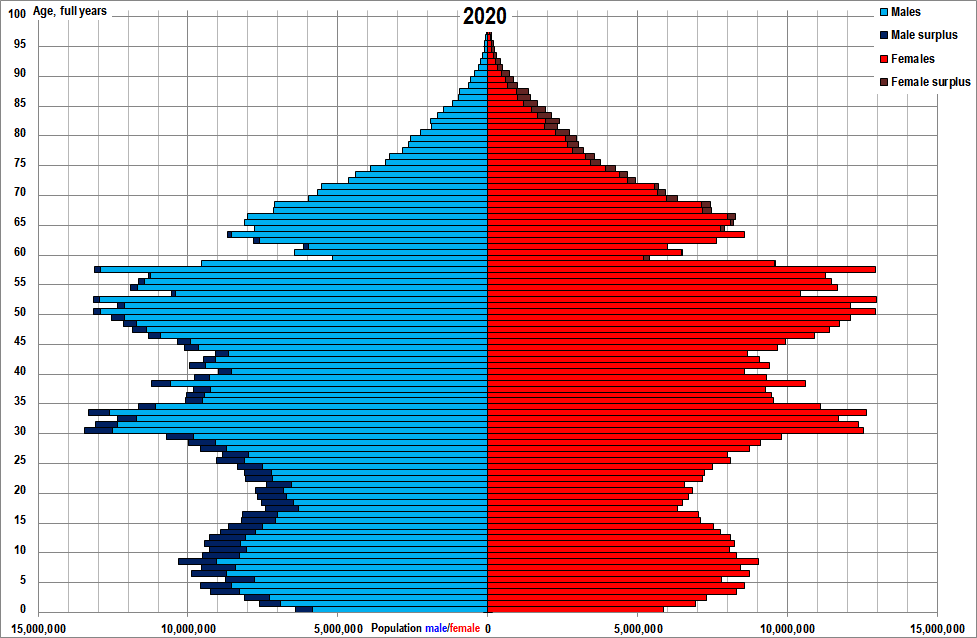

The gradual shift of the ‘world factory’ tag from China to Vietnam signals a loss in price competitiveness of labour-intensive manufactured exports – the demographic dividend that China has been benefiting from since its 1978 reform. Responding to the slowdown of population growth, the Chinese government has introduced a series of fertility encouragement policies since 2011: the ‘one-child policy’ implemented in 1980 was replaced by a ‘two-child policy’ in 2015 and the recent ‘three-child policy’ in 2021. Despite these measures, the fertility rate dropped to 1.3 in 2020, significantly below the fertility replacement rate of 2.1. A succession of supporting policies was hence introduced, including the most famous ‘double-reduction policy’ to reduce the burden of expensive cram schools, extension on maternity leave, and allowance on housing, tax payment and childcare.

Before considering childbirth, what about marriage?

The demographic issue in China is not only about the fall in fertility, but also marriage intention. The record of first marriage registration, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, has dropped drastically by 41% from 2013 to 2019. Therefore, the interview I conducted incorporates both marriage and childbirth intentions, to explore opinions towards Chinese fertility policies from the cohort of unmarried young Chinese females born in the 90s, who are the childbirth mainstay in the forthcoming years. Their responses reflected an increasing reluctance towards marriage and childbirth, given the current policy ineffectiveness and irresponsiveness. This observation is summarised in three themes:

1. Self-identity under Prevailing Norms

A conflicting notion was highlighted by interviewees: while the traditional Chinese norm considered ‘marrying a man and having children to carry on the blood’ as an inevitable life stage, young women now have an independent identity which they often find hard to reconcile with being a ‘mother and wife’:

“My value is reflected by my hard work and the money earned as an ordinary person, but not a mother or wife.”

One interviewee highlighted the legacy of the previous one-child policy on the creation of self-identity:

“…the changes that have taken place in the country…Our generation is mostly the only child in the family because of the previous birth control, the absence of siblings in our youth made us more towards individualism.”

2. Weakened Sense of Security

The maternity leave for female employees has left a series of repercussions regarding occupational gender inequality. All three interviewees pointed out this policy-induced discrimination:

“Having a child can have a very serious impact on your career.”

“From the company’s point of view, granting a female employee maternity leave is equivalent to keeping an idle person for 10 months.”

The recent extension on maternity leave received even more negative comments:

“It further squeezed women out of the workplace. No matter how long the leave is extended, the fear of their position being replaced by someone else at any time remains unchanged.”

More broadly, their lack of security, due to the increasing observations of unfair lawsuits and media censorship on gender-related crimes, also exacerbated their reluctance to marriage.

One participant criticised the ‘cooling-off period before divorce’ policy in 2020:

“Its introduction…sunk Chinese females into a very insecure position in marriage. These inadvertently created some psychological shadows for women and make them even more reluctant to get married…domestic violence laws are now almost non-exist. Any violence by a husband can be covered up as a ‘domestic dispute’.”

The other interviewee also expressed her frustration with media and police response to a notorious female trafficking case in 2022:

“My repost of the Xuzhou chained woman quickly disappeared. The police promised to investigate but their report months after literally said nothing.”

3. Social Involution

The third observation is a particular social phenomenon in Chinese young generation, where all sectors in society are immersed in unnecessary but endless competition, without significant improvements in productivity and innovation.

The so-called ‘involution’ in China can start at a very young age. The ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ mentality has made many expensive extra-curricular activities and personal tutorials almost compulsory for families:

“When every other kid starts learning computer programming as an extra-curricular activity, you certainly don’t want to lose at the starting line of the race. But how ridiculous. We never expect kids to learn that at kindergarten age.”

However, the ‘double-reduction’ policy, which aimed to alleviate such financial burdens by banning all tutorials and private educational institutions has created more chaos:

“Millions of people, who are parents too, lost their jobs overnight. And the rest went into the even more expensive informal market.”

How have fertility policies underperformed?

The first segment of underperformed policies is those introduced with good intentions but generated further problems: the double-reduction policy only considered the reduction of educational burden but failed to accommodate the unemployment of people working in such a large industry; the maternity-leave extension only addressed the inequalities faced by women in pregnancy but failed to realise the root of implicit gender discrimination even at the recruitment stage. One participant concluded at the end of her interview: “at this moment, not a single policy was created from a truly women-centred perspective’”. This can be traced back to the low female political participation in China, which ranked 118 among all 155 countries in the Global Gender Gap report.

The second segment is policy irresponsiveness on highly contested and pressing issues: the under-developed anti-domestic violence law, the introduction of the cooling-off period before divorce, and even media censorship on gender crimes all exacerbated the fear of marriage.

The last segment is the legacy of previous policies. The one-child policy has created a unique demography of almost a whole generation of nuclear families with only one child. Therefore, females in the 90s cohort find themselves in a difficult position between the cultural discipline on family roles and their awakened self-identity and individualism.

What does it mean for China?

The pitfall behind such a low fertility rate in China is an ageing population. On one hand, the ‘social involution’ of education may (or may not) inject productive and talented human capital into the Chinese economy, facilitating its ‘Made in China 2025’ ambition to successfully upgrade its industries within the Global Value Chain and avoid the middle-income trap. On the other hand, the current demographic deadlock means an excessive pension burden for the next generation. Therefore, the exigency of a reorientation of fertility policies is clear. Policymakers should realise the current encouragement policy that solely targets childbirth reluctance is not enough to resolve the core problem. The circumstances faced by millions of young women behind their reluctance reflect a gender issue embedded in Chinese society. This has been, unfortunately, neglected in current policies due to the low female political participation.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main Image credit: Official still image from the hit Chinese TV show ‘Nothing but thirty’, source: https://weibo.com/u/7161962323.