In the UK, local councils are uniquely poised to catalyse the transition to sustainable financial systems

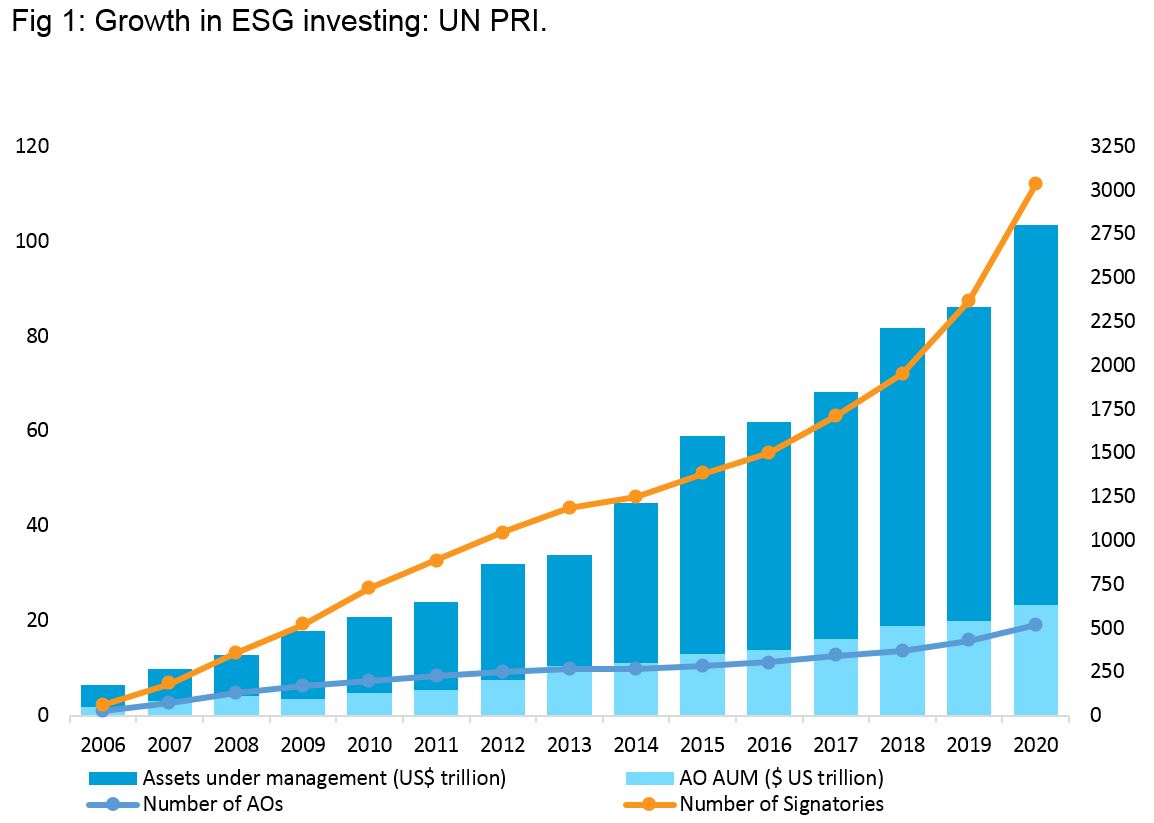

Few would refute the claim that sustainable finance is anything but mainstream. True, a few years ago it was a niche segment. For instance, in 2006 when the UN PRI (Principles for Responsible Investing) came into existence, 63 signatories signed up. Today, more than 3000 asset owners and asset managers have subscribed to the principles. In effect, they have agreed to do their bit to incorporate ESG factors in their investment practices. ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance factors; a broad universe of non-financial indicators of organizational performance ranging from climate action to transparent governance and employee engagement.

The incentives to engage with these factors are relatively straightforward. Research suggests that the argument that ESG investing demands a reluctant acceptance of lower returns is a myth. Over the long term (10 years), ESG funds have outperformed conventional funds. In addition, companies who align their business models with ESG investor expectations have been shown to have lower reputational risk , higher capital market valuations and greater profitability.

It is therefore no surprise that greening finance and financing green ranks high on international and national policy agendas. However, trends at the national or international level often mask the developments at a much more granular level; at the level of the local government.

In the UK, local councils are uniquely poised to catalyse the transition to sustainable financial systems. In order to do so, councils in the UK have two key arrows in their quivers; the council’s treasury management frameworks and the Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS).

Data from the LGIU/MJ State of Local Government Finance Survey 2020 suggests that 98% of local councils are committed to tackling climate change, the ‘E” of ESG. A rather expensive goal; financing green projects would mean increasing borrowing or raising council taxes given that 75% of all councils lack confidence in their financial sustainability.

This implies that turning purpose into action requires policy innovation and political consensus.

Innovation is about taking on the first mover risk in the hope that it transforms into a first mover advantage

Innovation is about taking on the first mover risk in the hope that it transforms into a first mover advantage. For instance; in 2019 West Berkshire declared a ‘climate emergency’ responding at the time to wider public sentiment in favour of such a move. Later in the same year, the council outlined its plans to use community bonds to finance green infrastructure projects. In the eyes of one observer, this was West Berkshire’s ‘bid to become a pilot authority’. Crowdfunding as an alternate to the PWLB as a source of finance was hitherto uncommon, but the council was advised that crowdfunding was cheaper and allowed greater certainty over borrowing costs. Not to mention, community bonds build engagement between the council and residents.

In May 2020, Warrington Council followed suit with a community bond scheme to fund a solar farm. Today, ‘Community Municipal Investment’ (CMI) is being heralded as a beacon of change in green finance. In the 2020 survey mentioned earlier, 9% of councils said they were considering CMI schemes. This is what policy innovation could look like; one or more councils willing to take on risks and consequently setting precedent.

Consensus is the other side of the coin; innovative ideas don’t turn into policy unless they are voted upon and backed by political consensus. Once consensus is built within the council, as it was in West Berkshire’s case, it must quickly translate into consensus across councils. History suggests that policy convergence proceeds in many ways from institutional learning; capital account management policies often reflected a country’s perceptions of what worked and what failed in other economies. Precedents are therefore powerful when documented and communicated effectively.

Turning purpose into action requires policy innovation and political consensus

LGPS and Stewardship

The LGPS, administered through local councils, is the other significant channel through which local government in the UK engages with ESG. The first fact to note about the LGPS is scale: it is one of the largest public sector pension funds in the UK with over 5 million members and 10,000 employers. Latest figures estimate the market value of these funds at above 280 billion pounds, 6% increase Y-o-Y. With such scale comes the ability to influence market participants and drive market trends.

One such trend is stewardship. There are various definitions of what stewardship entails. These definitions are usually drawn from stewardship codes or guidance released by financial regulators and investor coalitions across the world. The UK Stewardship Code posits that “Stewardship is the responsible allocation, management and oversight of capital to create long-term value for clients and beneficiaries leading to sustainable benefits for the economy, the environment and society”.

These codes are not mandatory and in the case of UK and Denmark, follow a ‘comply or explain’ framework which favours self-regulation. The UK was the first to adopt a code in 2012. Many more economies particularly those in North America and Western Europe were quick to follow. Across the world, both developed and developing countries are part of this trend.

Stewardship codes have implications for LGPS and the councils that administer them. They shape and positively impact the fund’s ESG capabilities, voting practices, fund governance and disclosure processes.

The 2020 UK Stewardship code has paved the way for two crucial developments: standardization and collaborative engagement. The code raised disclosure requirements, a move that is expected to bring about standardization. Standardization, in turn, is a catalyst for comparative analysis; if members wish to scrutinize how well a given fund performs relative to peers, standardized data is the first port of call. Standardization is crucial; there is no consensus on what constitutes ‘good stewardship’ and if an absolute definition is not available, a relative one is rather valuable. The new code also calls for collaborative engagement, arguably playing into the LGPS field of competence. The expectation being that this increases engagement influence and improves outcomes. Some observers believe that the new code has ‘raised the bar’ and it expects more from institutional investors such as the LGPS.

To that end, the evolution of stewardship practices at the LGPS reflects the fund’s (and administering council’s) ability and willingness to ride the ESG wave, as arduous as that journey may be.

It’s an honor to understand the play of ESG in innovation. I do believe all the institutions need to understand the importance as brought out by the author.

Appreciate reading and will share within Indian diaspora to the best of my ability.

Very Good read !