Dr Mathias Koenig-Archibugi reflects on international aid for the health sector in low-income countries and how many more resources should be devoted to global health.

Like other analysts of international aid for the health sector in low-income countries, my attention has been mostly focused on the quality rather than the quantity of aid. For instance, is it true that health aid can be made more effective by reducing its “fragmentation”, i.e., by replacing many donors each providing small shares of the total with a few big donors that would provide the bulk of aid going to any given recipient country? But recent controversies surrounding the decision of the British government to cut its aid budget are a powerful reminder that quantity matters too. Has enough aid been given to the health sector of low-income countries in recent years?

The absolute figure does not seem low. Flows of development assistance for health originating from mostly Western governments and large private donors increased from $7.8 billion in 1990 to $41 billion in 2019. The figure is also substantial when compared to how much is spent for health care in low-income countries overall: there, health aid makes up about one-third of total health spending from all sources, public and private (the percentage drops to 3.5 in lower-middle-income countries). But the size of the flows is much less impressive if we consider that aid makes up such a high proportion of overall spending mainly because the latter is so low. In 2017, average health spending was only $119 per person in low-income countries, compared to $289 in lower-middle-income countries, $1,053 in upper-middle-income countries, and $5,825 in high-income countries (all at purchasing-power-parity US dollars). In other words, high-income countries spend on the health of citizens of low-income countries less than one per cent of what they spend on the health of their own citizens.

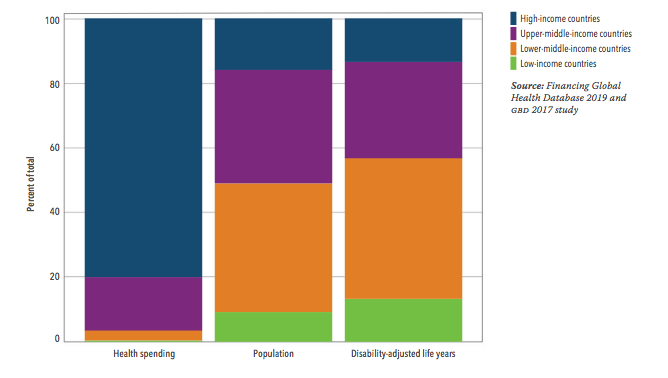

Another way of looking at this is to consider the amount of health aid spent for each “DALY”. The DALY (disability-adjusted life year) is a measure of disease burden that combines information on years of life lost due to early death and years lived with a disability. One DALY is equal to one year of healthy life lost. The diagram (Figure 4) below shows that the distribution of health spending across country groups defined by average income is strikingly different from the distribution of DALY lost to all diseases among those country groups. In some high-income countries, health-care interventions are considered cost-effective if they cost less than $50,000 per DALY gained (between 2003 and 2012, the English NHS is estimated to have produced health benefits at a cost between £5,000 and £15,000 per quality-adjusted life-year, a related measure).

Health spending, population, and disability-adjusted life years by World Bank income group, 2017

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Financing Global Health 2019: Tracking Health Spending in a Time of Crisis. Seattle, WA: IHME, 2020. http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2019-tracking-health-spending-time-crisis

How much health aid is spent in poorer countries to avert one DALY? It depends on the disease targeted by the expenditure. In 2017, about $4 of health aid targeted at HIV/AIDS were spent for each DALY lost in aid-receiving countries because of that disease – one of the highest ratios among all disease categories. By contrast, only a few cents were spent for DALY lost because of non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes. Common new-born and child diseases also received much less than one US dollar per each DALY caused by them. Overall, what is most striking is how little money is spent to help someone abroad to live an additional healthy year. It should be remembered that numerous health interventions for adults and children in low- and middle-income countries are able to avert the loss of a DALY at a cost of less than $100.

In other words, high-income countries spend on the health of citizens of low-income countries less than one per cent of what they spend on the health of their own citizens.

It is certainly important to understand how health aid is spent currently, with what results, and how it could be spent better. But it is at least as important to think how many more resources should be devoted to global health by those who can afford it, and how to make that happen. The economic crisis triggered by the coronavirus causing COVID-19 is putting public health budgets under pressure: domestic health expenditure in low- and middle-income countries is projected to fall substantially over the next few years. Given the difficulty faced by low-income countries, proposals to create a Global Fund for Health remain relevant. The aim would be to replace the patchwork of health aid delivery mechanisms with a single permanent mechanism that would collect resources from states in proportion to their financial capabilities and distribute them among countries according to disease burdens and needs (for instance, as measured by DALY). Certainly, setbacks are likely, as shown by the decision made by the current UK government on aid that has been mentioned earlier. But this should not prevent students of global health, international relations, and other social science disciplines from exploring pathways to the reduction of the staggering health inequalities highlighted in this contribution.

This blog was originally posted on the Global Health at LSE Blog. This is the fifth blog in the 12 Days of Global Health series.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and in no way reflect those of the International Relations blog or the Global Health at LSE Blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photo credit: ©UNICEF Ethiopia/2019/Mulugeta Ayene