In the light of the recent American recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the territory and recent EU trade agreements, Malcolm Cavanagh, student of MSc Theory and History of International Relations at LSE, 2020/21, looks at the EU’s position on the contentious Western Sahara issue and asks if the situation might provide opportunities as well as challenges.

Western Sahara (cropped) (CC BY 2.0) by bobrayner

In one of his famous foreign policy tweets this past December, former US President Donald Trump announced American recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the Western Sahara, a disputed territory about the size of Britain and with around 700,000 inhabitants. Morocco has occupied much of the territory since Spain left the former colony in 1976, and has been accused of repressing of free speech and illegal economic exploitation of Western Sahara. While the United Nations (UN) terms Western Sahara a Non-Self-Governing Territory which is illegally occupied by Morocco, few have challenged Rabat’s control over what it terms the ‘Southern Provinces,’ least of all the European Union (EU), which despite condemning Trump’s move to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over the territory has largely acquiesced and even tacitly supported Rabat’s position. Brussels verbally opposed America’s extension of formal recognition and maintained its support for UN negotiations on the matter, which have been ongoing since 1991. However, Brussels’ ostensible support for the UN negotiations is complicated by the contradictory activities of both European institutions and EU member-states.

Map of Western Sahara, credit DW

Through formal trade and political treaties with Morocco, the EU has informally recognised Moroccan control of the territory – however these agreements have routinely been struck down by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) as illegal under international law. In 2017, European Commission High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini promised that bilateral EU-Morocco trade agreements would be upheld despite the ECJ’s 2016 ruling that such agreements violated the EU’s commitments to international human rights law. The Court reiterated this position in 2018 when it ruled that the 2006 EU-Morocco Fisheries Agreement did not cover Western Saharan waters, thereby denying EU trawlers access to the territory’s fish-abundant coast. In response to the former ECJ ruling, Morocco suspended relations with the EU, a tactic which Rabat has reprised in responding to several EU member-states whose actions have been seen as critical of Moroccan ownership of the territory. The Kingdom has gone as far as blocking the opening of an Ikea in Marrakech over perceived Swedish opposition to Moroccan claims. Such actions have led to a virtual chilling effect among EU member-states; Irene Fernández-Molina and Matthew Porges observe that Morocco has made any public discussion of the Western Sahara virtually taboo.

It is in this restricted and confused space which a coherent EU policy on the western Sahara fails to materialise. The inconsistency between arms of the EU, and among member-states, has manifested itself very publicly, as the European Commission, Parliament, Council, and ECJ have varying and contradictory positions on the matter. Essentially, the EU is torn between its immediate interests in maintaining robust relations with Morocco, and its normative commitments to promoting liberal-democratic principles.

Essentially, the EU is torn between its immediate interests in maintaining robust relations with Morocco, and its normative commitments to promoting liberal-democratic principles.

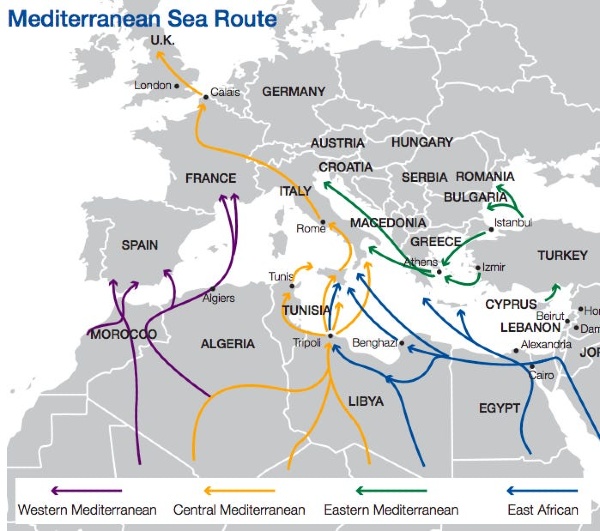

Europe’s economic interests in Morocco and the Western Sahara are substantial: the region contains the largest phosphorite reserves in the world, of which Europe is a leading customer. This mineral’s function as a chemical fertiliser is essential to maintaining Europe’s carefully orchestrated agricultural sector, which relies on phosphate exports from the Kingdom. Agricultural exports from Morocco to the EU topped 434 million Euro in 2019, and Morocco is a major market for European defence firms. Beyond its economic significance, Morocco is a major regional security partner for the EU. The European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) classifies the country as a “privileged partner,” and Frontex, the EU border agency, is permitted to operate in the country, effectively pushing the EU border to the southern shore of the Mediterranean. The Kingdom receives substantial EU aid in an effort to promote stability in North Africa, an embarkation point for migrants seeking to cross the Mediterranean northwards.

The EU-Morocco is further defined by the interests of several member-states, most notably Spain, the territory’s former coloniser. Spain possesses Europe’s largest fishing fleet, which has traditionally harvested the rich fish stocks off the North African coast; the country also holds two urban enclaves on the Moroccan coast, Melilla and Ceuta, thus requiring good relations with Rabat in order to avoid international crisis. Such a dispute is not unlikely; in 2002 the uninhabited Spanish-held Perejil Island was subject to invasion by Moroccan forces, which withdrew only after military pressure from Spain. A deterioration in relations with Rabat would spell diplomatic disaster for Spain (and by extension the EU), impacting not only the contentious issue of sovereignty over the Spanish Plazas de soberanía along the North African coast, but also Europe’s relationship with a key neighbourhood partner.

Chart of migratory flows from North Africa/Middle East to Europe

from “Migration and Its Impact on Cities – An Insight Report”

World Economic Forum, 2017

The EU’s strategic and economic interests in maintaining close relations with Morocco are paralleled by the Union’s commitment to promoting liberal-democratic norms through its external relations. European scholar Ian Manners describes the EU as a ‘Normative Power,’ deriving its global power from its status as a global leader in defining and promoting norms relating to peace, liberty, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. The diffusing of such norms is seen in the use of conditionality, the practice of requiring conditions pertaining to democracy and free speech be met in trade and aid agreements with foreign states, where the violation of such protections results in the termination of preferential status. However, EU scholar Klaus Brummer has criticised Brussels’ inconsistent imposition of penalties on partners which violate normative conditions – letting some violations slide when particularly significant relationships are at stake.

This is apparent in the case of Morocco, as the EU is unwilling to jeopardise good relations with a key neighbourhood partner, but is similarly unwilling to violate its commitment to the ongoing UN peace process by recognising Moroccan sovereignty over the territory. Gergana Noutcheva characterises the EU’s position on the dispute over Western Sahara as a product of the complicated situation on the ground, which is seen as only resolvable by the UN, as well as of the EU’s inability to adequately pressure Rabat on the situation without risking its vital interests in the North African region. The largely unrecognised nature of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), the state proclaimed by the foremost Western Saharan independence movement, the Polisario Front, further restricts Brussels’ ability to fully utilise its foreign policy competencies.

The EU is unwilling to jeopardise good relations with a key neighbourhood partner, but is similarly unwilling to violate its commitment to the ongoing UN peace process

While the Western Sahara issue presents a challenge to Europe’s credentials as a normative international actor, it also provides Brussels with an opportunity to demonstrate its commitment to cultivating its espoused norms through constructive engagement with Morocco. The Western Sahara situation is hardly black-and-white – the Polisario Front has long been accused of torture and human rights abuses, and Moroccan offers for devolved autonomous status (just short of sovereignty) for the territory has been lauded by some as a major step forward in negotiations. By engaging constructively with Rabat – which relies heavily on the EU as a trading and security partner – Brussels could demonstrate its expertise as an international moderator and ‘fair dealer’ to jump-start stagnant UN negotiations – a role which it enthusiastically took in negotiating the 2015 Iran Nuclear Deal.

Taking a leadership role on the issue could also improve the position of European leadership in two key areas: the Union’s position within the UN, and its relations with Africa. While the EU has paid lip-service to the ongoing negotiations, little concrete activity has backed up declaratory statements. Utilising its good relations with Morocco to make progress on the Western Sahara would mark out the EU as an international actor in conflict resolution, fortifying the Union’s position as an international actor. The SADR is a member of the African Union, providing an opportunity for Brussels to make inroads on a continent where the EU’s presence has been threatened several other powers. The Western Sahara has been a matter of international concern for decades, and while the current EU policy line (or lack thereof) on the issue presents a challenge to the EU’s international credentials, contributing to a constructive solution to the issue would not only reverse this inconsistency, but also enhance Brussels’ international standing as the normative power that it seeks to be.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Department of International Relations, nor of the London School of Economics.

2 Comments