Attempts by the Organization of American States to suspend Venezuela may not succeed. But as the Trump administration reshapes its relationship with multilateral institutions, there will be opportunities for “post-Western” diplomacy from within the region and beyond, write David Smilde (Tulane University) and Timothy M. Gill (UNC Wilmington).

Attempts by the Organization of American States to suspend Venezuela may not succeed. But as the Trump administration reshapes its relationship with multilateral institutions, there will be opportunities for “post-Western” diplomacy from within the region and beyond, write David Smilde (Tulane University) and Timothy M. Gill (UNC Wilmington).

In recent weeks the international response to Venezuela’s democratic crisis has been moving in new and uncertain directions. On 14 February, 2017, an updated report from the Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS) Luis Almagro called on the body to suspend Venezuela on the grounds that Nicolás Maduro’s government had violated practically every tenet of the OAS Democratic Charter.

Almagro’s direct resort to the maximum punishment surprised virtually all observers and received a muted response from the region. Even Peru, the most critical of Venezuela’s South American neighbours over the past month, expressed reservations about Almagro’s recommendation, suggesting that such a step would require prior consultations. Uruguay suggested it does not support invoking the Charter, as did Costa Rica. As such, Almagro’s new initiative could get fewer votes than the twenty cast in support of discussing his first report in June 2016.

However, a group of fourteen countries will soon be coming out with their own declaration urging Venezuela to: release political prisoners, recognise the opposition-controlled National Assembly, and establish an electoral calendar. Excepting Belize, which has opted to stay on the side-lines now that it holds the presidency of the OAS Permanent Council, this is the same group of countries that signed a similar document at the OAS General Assembly meeting in Santo Domingo in June 2016. But, according to Mexican Foreign Minister Luis Videgaray, the group’s statement differs from Almagro’s insofar as it does not impose a 30-day deadline and sees suspension only as a last resort.

The US is part of this initiative but so far has said precious little about Almagro’s recommendations. This is good because boisterous support could turn off many Latin American countries, always wary of appearing to support US intervention in the region.

While it is unlikely that Almagro’s proposal to suspend Venezuela from the OAS will receive the support of member countries, they could decide to support the fourteen-country proposal being developed as an alternative, invoke the OAS Democratic Charter, and then begin a period of “good offices” (i.e. fact finding missions and diplomatic measures). Were this to happen, it would represent the first invocation of the OAS Democratic Charter against an elected government.

Even if the support necessary to invoke the OAS Democratic Charter cannot be found, other avenues remain open. The Southern Common Market (Mercosur) has already marginalised Venezuela from full membership, and it too has a democratic clause that has yet to be applied. The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) is also close to selecting a new Secretary General: most candidates are likely to take a firmer stance with Venezuela than the incumbent Ernesto Samper.

But of course the engagement of multilateral institutions is difficult for the same reason that it’s effective. While it brings into play all of the member-states of a given institution, it also requires that they develop common understandings and agree on joint postures and actions. For example, insiders suggest there is little chance that Uruguay will support the invocation of Mercosur’s Democratic Clause unless Venezuela’s 2018 presidential elections do not happen or are openly fraudulent.

Potential involvement of the Inter-American System in Venezuela is being altered by the apparent US realignment with multilateral institutions that is taking place under the new administration. President Trump’s preliminary budget includes a 28 per cent cut in the State Department budget, which will reduce the US contribution to the OAS. And last week the US refused refused to send a representative to a hearing of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which was to include a discussion of the US travel ban’s impact on refugees. Such tactics, usually employed by pariah states and serial human rights abusers, risk seriously reducing US influence in the region and beyond.

Is this the beginning of a regional realignment of power? And if so, what will it mean for Venezuela?

Brazilian scholar Oliver Stuenkel has been working to theorise what a “post-Western” world will look like. He takes issue with the idea that a world without US or European leadership will be chaotic, violent and undemocratic, arguing that such a view overestimates how successful Western interventions have been and overlooks successful non-Western interventions. Indeed, it was the Contadora Group (comprised of Colombia, Mexico, Panama, and Venezuela) that achieved peace in Central America in the 1980s, providing a negotiating space that eventually spawned the Esquipulas Accord for which Costa Rican president Óscar Arias won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987.

A “group of friends” approach could also pay dividends in contemporary Venezuela. As Stuenkel himself has noted, just such a group proved key in navigating the extremely sensitive period following the 2002 coup. Membership of the group – and particularly whether the US should be part of it – would need careful consideration, but the idea itself is a step in the right direction.

Berating the lack of unity among Latin American countries is a favourite pastime of Washington policy circles. However, “groups of friends” are often able to overcome differences among countries through their reduced focus. And the Trump administration’s increasingly aggressive rhetoric towards Mexico is already pushing that country into greater contact with the region, thereby increasing the possibility of a regional solution.

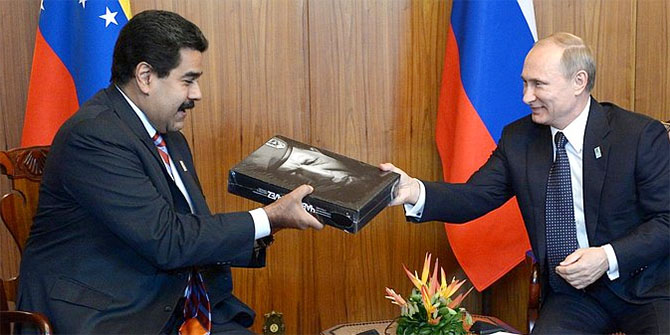

Latin American countries are not the only possible sources of post-Western influence in Venezuela, however, and we also need to consider the role of China and Russia.

China has a lot invested in Venezuela, and Russia increasingly so. And Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and hostility towards other trade agreements will inevitably increase China’s involvement in the region. China could seek guarantees of those investments by requiring Maduro recognise the National Assembly. China is said to have met with members of the Venezuelan opposition to ensure respect for Chinese investments and debt servicing. And as the Venezuelan economy falters, Maduro is allegedly finding it difficult to maintain his commitments to both China and Russia. It is not inconceivable that given the right guarantees, the two powers that have been instrumental in keeping Chavismo afloat might eventually prioritise economic interests over ideology and seek to alter the status-quo.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting