The divergent reactions of Britain’s Theresa May and Colombia’s Juan Manuel Santos to crucial yet dysfunctional referenda reveal a great deal about the nature of democracy and leadership today, writes Jean-Paul Faguet.

The divergent reactions of Britain’s Theresa May and Colombia’s Juan Manuel Santos to crucial yet dysfunctional referenda reveal a great deal about the nature of democracy and leadership today, writes Jean-Paul Faguet.

• Disponible también en español

2016 served up two extraordinary referenda, fought under similar conditions, and with similar results, but which led to remarkably different outcomes.

Here in Britain, a new prime minister grimly prepares to trigger fundamental changes to the nation’s economic and legal affairs that she knows will leave it poorer, weaker and smaller. In Colombia, a historic peace is implemented, and the continent’s largest, fiercest, and longest-lived insurgency emerges from the jungle and prepares to disband. How did this happen? This tale of two referenda is interesting in its own right but also for what it teaches us about democracy, leadership, and the meaning of political courage.

First, the similarities. Like the UK, Colombia’s government called a referendum on an issue of transcendent importance. Like the UK, its government was confident of victory; the cost-benefit calculus seemed obvious. Like the UK, Colombia’s No campaign was led by prominent populists who deliberately ignored the main issues, instead exploiting social media to stoke voter indignation. Their strategy also relied on hyperbole, fabrication, and outright lies about the consequences of a Yes victory: Colombia would become an atheist country; children’s gender would be undermined at school; pensions would be cut to fund decommissioned guerrillas; FARC leader Timochenko would automatically become president; children would be recruited by homosexual evangelists; peace would turn Colombia into another Venezuela; and my personal favorite: the government had designed secret referendum pens that erased No votes. There were more. Like the UK, none was based on fact. And like the UK, facts didn’t matter.

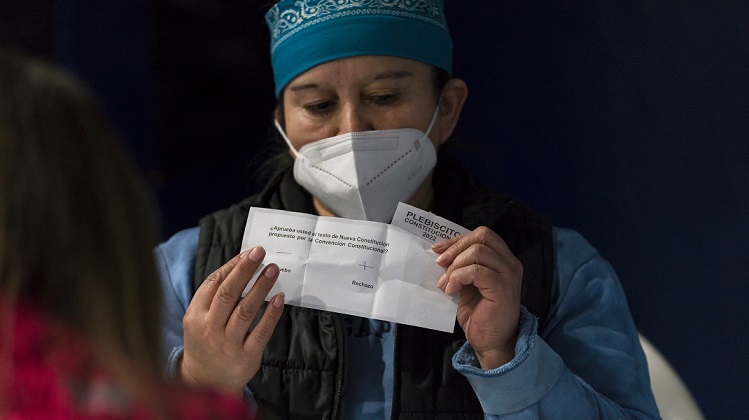

Finally, like the UK, the government narrowly lost. If the British margin of defeat was modest (52 vs 48 per cent), Colombia’s was miniscule (50.2 vs 49.8 per cent) – 54,000 votes in a country of 49 million. The result left both countries staring into a void. Would Colombia revert to war? Would Britain turn its back on Europe? What comes next?

The latter is a surprisingly difficult question to answer. In both countries, No/Leave leaders demanded that democracy be respected. But a plebiscite does not equate with “democracy”. It is one specific tool that, like any tool, can be used well or badly. “Democracy”, in the sense intended above, cannot be reduced to plebiscites. It emerges, rather, from a complex of laws, organizations, and norms and practices. Democracy is not so much a “thing” as an aspiration – of government by and for the people. The important question is how to achieve that.

In representative democracies, voters elect politicians, whose job it is to study public issues, carefully weigh pros and cons, and choose on behalf of citizens. Policy-making is done by specialists; citizens are free to live their lives. Guaranteed rights and checks-and-balances protect the interests of individuals and minorities. Such systems are often adept at incorporating technical expertise into decision-making, and their cost per citizen is strikingly low. But the flip-side of specialization is that government can appear distant and detached.

Where do plebiscites fit in? As an injection of direct democracy, a reinvigorating dose of mass participation? Actually, no. Amongst political scientists, “plebiscitary democracy” is a term of abuse. Plebiscites over-simplify complex issues into yes-no questions, and are subject to momentary passions that can be easily manipulated. And often they are – witness Britain and Colombia. Better examples include referenda that confirmed or extended Mobutu, Mussolini, Pinochet and Hitler’s hold on power. All of these were comfortable victories for despots; all were tragedies for democracy.

In a democracy, holding plebiscites on big, complex issues that are likely to affect the nation’s economy, politics and society for generations to come is incoherent – the wrong tool for the task. It is also cowardly, a sign of politicians ducking difficult choices. And it is irresponsible, a rank refusal by politicians to do their jobs.

Now return to the post-referendum void. These are extraordinary moments of uncertainty when sharp changes in trajectory become possible, and leaders wield far more power than normal. The decisions they make at such “critical junctures” shape events in ways that come to seem inevitable, but were not. In Colombia and Britain, leaders certainly seized their moment. But in very different ways that shaped very different futures.

Accepting responsibility for his loss, David Cameron resigned as UK premier, and Brexit leaders fell shambolically by the wayside. Theresa May, an experienced, canny politician, attained power unopposed and unelected. “Brexit means Brexit,” she, a tepid Remainer, declared, and sent the nation down what she knows to be the worse of two paths. The lies that stoked Brexit remain standing. She implements what the electorate – deceived, manipulated – thought it wanted one day in 2016.

Juan Manuel Santos, by contrast, opted to lead. Giving up would have been easier – war is business as usual in Colombia. Persisting with peace was easily the more difficult path. But the rewards for Colombia are immense. And Santos – one of the country’s most successful defence ministers – understood that better than most.

Visibly chastened, he went back to work. “No” campaigners demanded 57 changes to the accord. Government and FARC agreed 56. The new accord was put to Congress, as the constitution demands, and as previous agreements with smaller insurgencies had been. Peace was ratified, reception centers readied, and then Colombians watched transfixed as thousands of FARC fighters emerged from the jungle and laid down their arms.

During all of this, Santos was lambasted for “democratic treachery”. But where, exactly, does democracy lie? In the deliberations and acts of elected Congressmen, or in a referendum result? And where is the treachery? In his failure to “respect the referendum”, or his failure to return Colombia to five decades of war that killed 250,000 and displaced 8 million more?

To take risks and persist in the face of failure, in pursuit of a better future, is the very definition of leadership. At the critical juncture, Santos proved himself a leader and a statesman. Would that Britain, too, were led by leaders, and not followers.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article was originally published at Social Europe

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Dear Mr. Faguet,

Thank you for your answer. After reading your response and the comment of Andrés there are a few points that need to be highlighted.

First, comparisons between the UK and Colombia are completely out of proportion as their political systems are utterly different; their levels of education differ in great magnitude, especially when we look at political education. Comparing both referendums is a big simplification of a complex social process. In the UK, the referendum was the result of a failed political strategy. If we accept to compare and conclude about both cases, then we are implicitly saying that Colombia’s referendum is just a strategic mistake of a government that failed at explaining what “peace” means.

Plebiscites are indeed tricky democratic instruments. However, just because we do not like their outcome, doesn’t mean that the instrument flawed. They require a thorough understanding of their constituents. It is worthy to involve communities in their own in political processes. For instance, the successful story of Medellin is a vivid example of the positive effects of well-managed public participation. The only similarity between Colombia and the UK, is that both referendums were astonishingly bad managed by their governments.

Contrary to Brexit, Colombia has a long repertoire of experiences in peace processes and has a fairly good idea of how things usually play out. Aiming for peace is nothing new in Colombia. In the last years, we have gone through more than 8 failed peace processes. It was unexpected to observe President Santos failing at securing support, even when he owns extensive political machinery.

Colombian history is so cyclical; than one has to wonder why do we keep ignoring the lessons learn in the past? Colombia is a centralist country. Since our Independence Declaration in 1810, we have been living a disconnection between what the government does and what people need. This is the main cause of our internal conflicts, like the emergence of guerrilla in the 60’s and paramilitary in the 80’s.

We have an opportunity to explain to our fellow Colombian how important is to live in peace, and it is not about a simple policy owned by a government. Peace belongs to everyone who lives in the Colombian territory. We are not going to live in peace after the peace process considering all the social injustices and inequality issues that we continue to face. We know that politicians lie to obtain what they want. These are trues that you have to deal with. Unfortunately, Santos’ government did not do its homework well at the moment to share with the people what this referendum was about by using all the state capacity, and you can see its result.

Dichotomies lead countries to polarization and claiming that peace it’s only possible if we accept the negotiation of the Santos’ administration and the FARC is putting the country in front of one; either Santos’ peace or none. That is just not true. If there is a real political will of constructing peace that goes beyond this administration, then the right step is to re-negotiate, considering the input of the referendum, an input that a yes or no question cannot provide. It is unacceptable to expect people to approve whatever you do, just because you claim your goal is a good one! After 50 years of civil war, a constant high GINI Coefficient, huge differences between rural and urban development, do we really believe peace will come from a treaty negotiated between an unpopular president and an even more unpopular guerrilla? Peace should be a state policy, starting by providing state presence in the whole Colombian territory. We are not suggesting double-thinking arguments, we are asking for a deeper analysis.

Once again, during the campaign, Santos’ government lied about the guerrillas´ salaries, no jail for war crimes, drug trafficking revenues and weapons hidden, war after the rejection and so on. We are only highlighting the lack of transparency, justice, trust and strong leadership during the whole process.

Now, the government is worried about the latency of the peace agreement implementation, handover of weapons and money and upcoming elections in 2018. People are losing their hope on this process and the Constitutional Court is rejecting some proposals approved by the Congress using the “Fast Track” mechanism. There is still no consensus how to hand over the peace agreement to a new government. So, there is still work to do if they want to implement the agreement successfully.

As academics, we believe in evidence and should base our arguments on it. Overstating facts is what causes massive movements against the establishment. Please explain us, where should we draw the line between an acceptable and an unacceptable lie? When is lying justified? So, if we claim we want peace, then is every lie, argument and corruption justified? Bringing peace excuses me from providing my land with stable and respectable institutions? Honestly, we don’t see a big difference between the Leave (dishonest vituperative) campaigns and the “exaggerated” arguments of technocrats. Overstating a fact is a fancy way of lying. And that’s exactly what the Colombian Government has been doing for the last 5-8 years.

Kind regards,

Ingrid von Schiller and Sebastian Gallego

Al leer el artículo “Cobardía y coraje: la historia de dos referendos” de Jean-Paul Faguet, profesor del London School of Economics, me parece escuchar la explicación dada por miembros del Gobierno colombiano, o de un ex alumno de LSE que trabaja para el gobierno. Esa habilidad de interpretar la verdad según contexto, me hace pensar que hemos perdido la objetividad de las publicaciones o análisis académicos basados en evidencia. Negar los hechos y disfrazarlos de lo que nos gustaría que fueran, nos ha llevado a crear a ese rencor y votos de desconfianza contra el establecimiento, cuyos resultados inevitables han sido los comicios en Estados Unidos, Colombia, Argentina, Perú y Reino Unido.

“¡Por Dios! ¡Una expresión del realismo mágico!” Diríamos en Colombia, si leyéramos detenidamente el artículo del señor Faguet. Al respecto considero pertinente exponer otra mirada sobre la situación política y social que se vive actualmente en el país. Señores, ambos grupos de apoyo tanto los del NO como el SÍ usaron las mismas estrategias electorales durante la campaña, generando miedo a lo desconocido, unos diciendo que nos vamos a parecer a Venezuela, y otros diciendo que vamos estar en una Guerra Urbana. Otros diciendo que el país tiene repúblicas independientes para las FARC, y otros diciendo que el proceso de negociación se iba a acabar definitivamente y las FARC volverían a ejercer violencia en la ruralidad colombiana. Va uno a ver y ninguna de esas cosas ha pasado. Todo fue una mezcla de mentiras y manipulación. El resultado del plebiscito es un hecho, y el Presidente rompió una más de sus promesas, una hecha frente a un medio de comunicación británico de renunciar si perdía el plebiscito (19 Nov 2015). Independiente del plebiscito y su resultado Colombia sigue teniendo violencia, polarización política, sí un nuevo acuerdo, pero seguimos en las mismas.

¿Cómo un presidente que tiene el nivel más bajo de popularidad de la historia puede lograr que la gente votara por el Sí en el Plebiscito (Menos del 17%; YanHaas Poll, Abril 2017)? Es una falta de respeto con la ciudadanía convocar elecciones en menos de tres meses y no ejercer una tarea pedagógica previa en las regiones. Nadie empoderó a los académicos o usó las redes sociales para impulsar la campaña por la Paz como si fuese una política de estado. Si eso era lo que Santos quería, debió despersonificar el acuerdo, al final no es de él, es de los colombianos. El acuerdo de Paz y su referendo no se planteó desde un enfoque humano o social, partiendo del lado de la gente. Por el contrario, tuvo una perspectiva de un presidente que ha sido ajeno a la realidad del país y su gente, que le falta ponerse la camiseta de la selección para sentirse parte del sufrimiento al que las malas gestiones públicas han expuesto a miles de colombianos. Santos terminará siendo un presidente con un Nobel que quedará en la lista de los lindos recuerdos de quienes intentaron, pero no pudieron entender a Colombia.

Hay que hacer el bien desde el principio en la política como suele decirlo el exgobernador de Antioquia Sergio Fajardo. “Hacer las cosas a las patadas” (expresión coloquial) eso no sirve en Colombia, ni en el mundo. Por favor Señores Políticos, dejen el ego a un lado, y así tome un poco más de tiempo, vayan eduquen y trabajen con la gente. Ojalá, estos plebiscitos y/o elecciones alrededor del mundo hayan servido de lección para entender que los políticos no son inmortales, la paciencia de los electores tiene un fin y cada acción o inacción su consecuencia.

La paz es un derecho máximo que solo se puede lograr si mejoramos las capacidades del Estado Colombiano. Una justicia ineficiente que ofrece beneficios a los corruptos o ladrones de cuello blanco, es una justicia vendida que imposibilita la paz. Un gobierno que no educa, es un gobierno irresponsable. Un pueblo que no participa, es un pueblo sentenciado. Así que, ojalá podamos ver algún día líderes que sí sepan aprovechar su capital político y trabajen por brindar una vida digna a los colombianos. De esta manera, Sr. Faguet antes de emitir un concepto frente a la sensible realidad colombiana con el peso de una institución tan respetada como LSE, sería importante conocer las circunstancias y matices en los que se va a leer su opinión.

Dear Ms von Schiller and Mr Gallego,

Thanks for your reply to my piece in El Espectador, re-published on the LACC blog. I appreciate that Colombia’s peace referendum elicits strong, and strongly-held, views amongst serious, thoughtful people. This is hardly surprising, as questions of war and peace are amongst the most important faced by any society.

I presume that most readers of this blog operate more comfortably in English, and more will have read my piece in its original English version. Hence I will answer you in English.

I take your point that the Yes campaign was too closely allied to President Santos. A better, more effective campaign would have been independent of the government, and strongly rooted in civil society, private firms, and the opposition. Interestingly, this is yet another similarity between Colombia and the UK. Recognizing the problem, the British Remain campaign tried to establish itself as non-partisan, multi-party, and independent of the government. But in practice it was closely tied to David Cameron and most of his cabinet. This allowed No campaigners in both countries to encourage voters to kick the government in the shins by voting against the official position. Which, in my view, is what many voters in both countries did.

Claiming that “both sides lied equally” is, I’m afraid, simply untrue. In Colombia, the government over-egged its argument in ways that happen in any debate and any campaign. This does not excuse it. But that is qualitatively different from the blatant lies and deceptions in which the No campaign wallowed. The same is true of the UK, where experts and technocrats exaggerated arguments based on fact (I include myself), while Leave campaigners simply made stuff up. Hence the non-existent £350 million a week, or assurances that the UK could have free trade without free movement. This is simply rubbish, and the politicians peddling it knew it was rubbish. Events since the referendum leave no doubt that both claims were lies. I don’t doubt that in both countries, many Leave/No voters identified the rubbish. But after such dishonest, vituperative campaigns, I suspect many others didn’t. The latter are in for a nasty shock that may well undermine their faith in democracy itself.

In the UK, it is politicians who claim Brexit will benefit the economy. Economists know that breaking away from the UK’s, and the world’s, largest market, and its companies’ most important value chains, will deal the economy a blow. The only serious arguments are about how big, how soon, and will there be any countervailing effects. Here there is a lot of room for debate, as it’s never been done and no one really knows. Many economists and technocrats are guilty of over-confidence in our projections, of not acknowledging the big uncertainties (mea culpa rursus). But again, the unknowns are of degree, not type.

Lastly, the claim that the Colombian government lied when it said a rejection of the peace deal implied a return to war is a curious one. I have heard this over and over again in Colombia during the past year, and to be honest it sounds to me like double-think. What can rejecting peace mean, if not war? ‘No’ campaigners deployed convoluted arguments to claim that rejecting peace would lead to peace, because it was ‘this agreement’ they rejected, and the peace they wanted would be ‘a better peace’.

The peace deal was hammered out carefully in detailed, drawn-out negotiations between a government in a strong position (thanks in large part to the presidency of Alvaro Uribe) and the fiercest, longest-lived insurgency in Latin America. One can argue that it nonetheless should have been rejected. But not because doing so would lead to peace. That is magical thinking. Straightforward thinking says that rejecting peace leads to war.

The reason Colombia’s No vote did not lead to war is that President Santos re-negotiated key clauses of the agreement, and then pushed for it to be approved in the usual, Constitutional way. He could have simply given up, as the British political establishment more or less did. But he did not. Instead, he chose to lead.

Many thanks again for your comment. With best wishes to you both,

Jean-Paul Faguet

In general I agree with your comments and ideas, Indeed plebiscites are a nasty way to fold democracy to address short term goals, that usually benefit snake charmers. For example, another plebiscite was hold in a small municipality in Colombia, to ban mining within it. Such initiative raises many questions, as it could impair also construction and infrastructure development. There is a nasty habit by local communities in Colombia to demand extensive concessions not directly related with projects, turning, in many cases into blatant extortion.

I strongly disagree of your assessment of President Santos. There are some developments arising from the implementation of the peace accord that are clearly worrying, being a few; the mechanism for incorporating the accords within our legal framework is being abused, not only it allows little deliberation of what was “agreed”, there are initiatives not related to the accord that are being considered, for example, an opposition statue which ironically restricts political participation, and extensive reforms including mandatory voting, granting voting for people above 16th years old, etc,

Other thorny issue is the new framework for the judicial system to investigate what happened during the confrontation. It seems that the secretary general of the new body, an unelected, citizen, chosen by foreigners on behalf of the UN without a formal career in Colombia’s Judiciary was granted extensive judicial powers, even to the extent that is making statements about potential processes that are even rebuked by the citizens directly involved. Not to mention the explosive increment in Coca plantations; recently with the signature of the new agreement, there has been extensive conflict with local coca growers which are aiming for a standstill in the removal of these illicit crops.

Also, the managerial skills of president Santos have proven to be depressing. Construction of temporary facilities to house members of FARC is out of schedule and budget, and there are serious concerns about corruption, others that are already working showcase little control, allowing for uncontrolled entry which could lead to leakage of war materials. In new year, was really upsetting to see members of the UN mission dancing with FARC members, as they are supposed to oversee them. Also there is no clarity if FARC is going to demobilize all of its fighters, they seem to have kept the largest share of their militants within cities out of the scope of the peace accord, and even there are some worrying reports that they are transferring weapons to them.

At least, it has been announced that 2000 members of FARC will be hired as private bodyguards for their most senior members, with a salary that is almost 2.5 times the minimum wave in Colombia with full benefits. As a Colombian I am really worried about the prospect of having an institutionalized armed body out of the scope of regular armed forces.

Dear Dr Alonso

Thank you for your comment. I appreciate the finer grain of detail that you bring to this matter as, I presume, a researcher living in Colombia.

I didn’t mean my article as a general endorsement of President Santos, but rather as an interesting comparison of two experiences of referenda that in some ways were surprisingly similar, but ended up with remarkably different outcomes.

The facts you report are indeed worrying. I won’t comment on them further as I’m currently in Central America, and lack the information necessary to do so responsibly.

Thanks again for your comment. With best wishes,

Jean-Paul Faguet