Recent attempts to criminalise trade unionists involved in the 2009 French Caribbean general strike recall the trial of independence activists following the May ’67 Pointe-à-Pitre massacre in Guadeloupe, writes Grace Carrington (LSE Department of International History).

Recent attempts to criminalise trade unionists involved in the 2009 French Caribbean general strike recall the trial of independence activists following the May ’67 Pointe-à-Pitre massacre in Guadeloupe, writes Grace Carrington (LSE Department of International History).

Fifty years ago, 18 Guadeloupeans were put on trial in the French Court of State Security. Their crime? Openly advocating independence for Guadeloupe.

The 18 defendants were arrested in 1967 following major unrest in Guadeloupe, known locally as “May ’67“. Although the violence began when police opened fire on a crowd of striking workers, the French government blamed the clandestine independence movement, the National Organisation Group of Guadeloupe (GONG).

They arrested GONG members and anti-colonial activists suspected of having links to the group. During the controversial trial, these activists were supported by a range of public figures, including the renowned French philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, who testified in their defence.

Departmentalisation in Guadeloupe

To understand why these activists were arrested, it is important to realise that Guadeloupe at this time was technically not a colony, but an overseas department of France. In 1946, after centuries of slavery, colonialism, and neglect, Guadeloupe became an overseas department, along with Martinique, La Réunion, and French Guiana.

Departmentalisation made Guadeloupe an integral part of the French Republic and appeared to offer Antillean citizens the same employment, welfare, and political rights as enjoyed by metropolitan French citizens. However, in the twenty years following departmentalisation the continuing lack of parity with the metropole led to increased disillusionment and anger.

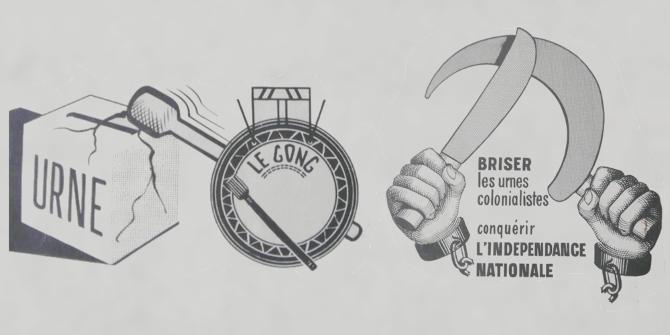

In mainland France, Antillean student organisations increasingly advocated for greater local autonomy. In 1963, GONG was established in Paris, and was the first group to explicitly call for Guadeloupean independence. GONG and other pro-autonomy groups were subject to considerable state repression, thanks to a 1960 decree which allowed the French government to control anyone who threatened the “territorial integrity” of France.

The May ’67 Massacre

On 26 May 1967, French police opened fire on striking workers in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe. Over the following 48 hours, it is estimated that between 8 and 200 people were killed in clashes between protesters and police. Initially, French officials announced that eight people had died, but witnesses and historians have cast doubt on this figure, which appears not to take into account the level of violence, the number of disappearances, and families’ fears of reporting deaths and disappearances to the authorities. The French government blamed the unrest on GONG.

May ’67 received very little coverage in the French media at the time and remains a controversial issue in Guadeloupe. Crucial archives on the subject remain closed, making it difficult to ascertain exactly who was responsible for the violence. A recent independent commission of inquiry confirmed that, though it was still difficult to determine the exact number of deaths and who was individually responsible, May ’67 was “a massacre during a protest, knowingly ordered on the ground, and approved by the government under the presidency of General de Gaulle”.

Guadeloupean nationalists began to be arrested before the violence of May ’67 had even subsided. Suspected independence activists were rounded up both in Guadeloupe and in Paris.

Ken Kelly, the editor of GONG’s journal, was working in Paris when he heard what was happening in Guadeloupe. Within a few weeks, the police knocked on his door and arrested him for crimes against the state. In an interview, he described how he and the other political prisoners were held in the same prison together and went on hunger strike in protest.

The 1968 Trial

Unlike May ’67, the trial of the 18 Guadeloupean ‘patriots’ in 1968 gained much media coverage in France. Student protestors gathered in Paris demanding the fair treatment of the imprisoned activists. This came just a few months before the turbulent civil unrest of May 1968 in France, which marked a major turning point in the nation’s history.

The trial lasted from 19 February to 1 March 1968. The defendants were all men aged between 28 and 46, from a range of professions: teachers, students, lawyers, doctors, journalists, mechanics.

During his testimony, one of the accused, Rémy Flessel, highlighted the gross disparity in response to strikes in metropolitan France, compared to Guadeloupe:

When there is conflict between the working class and the government in Brittany or Normandy, even if the workers use violence, they do not shoot at them, they are not imprisoned or deported, and [the government] negotiates with their representatives.

The famous French Caribbean intellectual and author of “Discourse on Colonisalism”, Aimé Césaire, spoke in favour of the defendants. Though he had played a crucial role in negotiating departmentalisation in the 1940s, Césaire had become critical of the continued inequality between metropolitan France and the overseas departments. Césaire began his court statement arguing that “there is no doubt that the French Antilles are de facto colonies”.

Yvon Coudrieu, a sports teacher, offered a moving testimony of his experience during the unrest in Pointe-à-Pitre in 1967. On the evening of the 26th May, he had been out trying to buy a gift for Mother’s Day when he was shot without warning by the police with a “dum-dum” bullet which blew apart his right leg.

Jean-Paul Sartre testified at the trial in support of the 18 Guadeloupeans. He argued “this trial… proves, precisely, that our Guadeloupean friends… do not have the same rights as French people from France and that, consequently, they are not French”.

Several witnesses referred to a “plot” against GONG, maintaining that the French Government was trying to undermine GONG’s legitimacy and find an excuse to suppress the organisation. Whilst the prosecution offered evidence that members of GONG had distributed pro-independence propaganda material, they were unable to provide any proof linking GONG to the violence in Pointe-à-Pitre the previous year.

Ultimately, six men, including Flessel, were given three to four years in prison for the “dangerous threat” that they posed to the French Republic. The other twelve, including Ken Kelly, were acquitted. GONG disintegrated after the trial, with so many key members in prison. May ’67 had provided a good excuse for French authorities to clamp down on the nascent nationalist movement in Guadeloupe.

Inequality in 2018

Guadeloupe’s difficult relationship with the French legal system continues to this day. In March 2018, Elie Domota, leader of the General Workers’ Union of Guadeloupe (UGTG) – the island’s largest union – was tried for an “act of violence” during a protest.

Domota has argued that his trial is part of a campaign to criminalise trade unionists in Guadeloupe, as he is the 107th member of the UGTG to receive a court summons since the 2009 general strike that brought Guadeloupe to a standstill for 44 days. During the trial, protesters gathered outside the court in solidarity with Domota. Ultimately, he was fined €300, but he intends to appeal the decision.

More symbolically, Domota’s trial shows that even fifty years after the imprisonment of the Guadeloupean independence advocates, tensions between the French state and political activists in Guadeloupe continues. The perceived criminalisation of figures like Elie Domota highlights the continuing inequality and colonial legacy in France’s treatment of its overseas departments.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Hello Grace,

I came across your article when wanting to research the events of 1967 while reading a novel (translated) on them by Gerty Dambury. Despite my mother coming from Guadeloupe this novel and your article were the first that I had ever heard of these appalling events. So thanks for writing what you did and posting it in the UK. Bernard

Madame,

Merci pour cet article.

Ayant fait partie récemment de la commission historique, composée de 8 historiens universitaires français et guadeloupéens, dirigée par le professeur Benjamin Stora, je tiens cependant à porter à votre connaissance le rapport qui en a résulté après 18 mois de travaux collectifs dans les archives françaises. Ce rapport est consultable en ligne sous format PDF aux éditions de la Documentation française (novembre, 2016).

http://www.outre-mer.gouv.fr/rapport-de-la-commission-stora

Pour votre information, ce rapport a écarté pour l’heure les hypothèses maximalistes du nombre de victimes allant jusqu’à 200 morts que vous évoquez pourtant dans votre article ! : “By 28 May 1967, anywhere between 8 and 200 Guadeloupeans had been killed (detail from Patrick Bauduin, BY-NC-ND 2.0”.

Mai 67 a bel et bien été un massacre, mais je tiens à vous faire remarquer qu’aucun historien universitaire français ou guadeloupéen n’a jamais évoqué ces hypothèses hautes s’agissant du nombre de victimes…

Attention donc à la méthode, car vous relayez là en réalité des chiffres que l’on retrouve sur les réseaux sociaux depuis quelques années, notamment depuis les mouvements sociaux de 2009…sans aucune preuve ni aucun faisceau d’indices !

Pour information, huit victimes ont pu être identifiés à ce jour aux termes des 18 mois d’enquête de la commission historique Stora.

Je reste à votre disposition si vous souhaitez échanger sur l’affaire de mai 1967.

Cordialement,

Sylvain MARY

PS : pardonnez-moi de ne pas avoir écrit en anglais. J’ai vu que vous parliez français. Mais si vous souhaitez me répondre en anglais, avec plaisir.

Thank you for your comment. That’s very exciting that you worked on the Stora report. I know it well. I’d encourage you to reread my article as I’ve discussed the reports findings and included a link to a summary of the report and the report itself: ‘A recent independent commission of inquiry confirmed that, though it was still difficult to determine the exact number of deaths and who was individually responsible, May ’67 was “a massacre during a protest, knowingly ordered on the ground, and approved by the government under the presidency of General de Gaulle”.’

Would be great to discuss your PhD research as it sounds like there are some interesting overlaps in our research.

Kind regards,

Grace