The UK already enjoys significant commercial, diplomatic, cultural, and defence links with many Latin American and Caribbean countries. But moves to address outdated perceptions of the region, to facilitate business engagement, and to streamline governance of these relationships could strengthen them even further in the post-Brexit era, write Joanna Crellin (UK Trade Commissioner for Latin America and the Caribbean) and Edward Elliott (British Foreign Policy Group) in preparation for our event on The Future of UK-Latin America and Caribbean Trade (25 February 2019).

The UK already enjoys significant commercial, diplomatic, cultural, and defence links with many Latin American and Caribbean countries. But moves to address outdated perceptions of the region, to facilitate business engagement, and to streamline governance of these relationships could strengthen them even further in the post-Brexit era, write Joanna Crellin (UK Trade Commissioner for Latin America and the Caribbean) and Edward Elliott (British Foreign Policy Group) in preparation for our event on The Future of UK-Latin America and Caribbean Trade (25 February 2019).

The region of Latin America and the Caribbean has always presented opportunities to the UK, yet it has also, at times, been overlooked. The Canning Agenda in 2010 was a welcome step towards strengthening the links between the UK and the region, and it provided the UK with a firm base on which to build its future relationship. But as the political landscape around the world evolves, including at home and in Latin America, the UK now has an opportunity to consider again what more we can do to drive forward our engagement with the region and the countries within it.

The British Foreign Policy Group’s recent report Revitalising UK-Latin America Engagement post-Brexit offers a real chance to assess the successes and limitations of the Canning Agenda, to provide new insights into the current state of these vital relationships, and to build on them going forward.

Trade and investment

In the past year, the UK has appointed trade commissioners for nine geographic regions of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean. The role aims to raise the profile of Latin America as a trading partner for the UK and to ensure that British companies are aware of the size, dynamism, and potential of this region. One of the key challenges around trade, as well as political and cultural relations, is the need to improve perceptions of Latin America in the UK.

In short, this is a region which UK businesses can no longer afford to ignore. With a population of 650 million people, almost double that of the USA and ten times the size of the UK, it is also home to three of the biggest cities in the Americas. Its status as the second most urbanised region in the world, with 78 per cent of its population living in cities, has led to a burgeoning middle class with an appetite for the kind of modern goods and services that UK companies can provide.

Diplomacy and soft power

Aside from economic issues, the British government has become increasingly aware of the greater role that Latin American countries are now playing in international politics. This has led to initiatives that enhance Britain’s physical presence in Latin America, with the notable reopening of embassies in Paraguay and El Salvador (which had closed down in the 2000s).

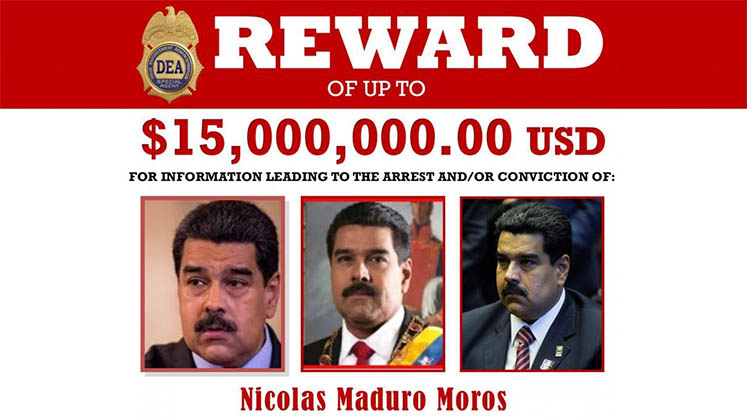

There are, however, political issues that have caused friction. Most recently, the UK has become particularly concerned about political and economic developments in Venezuela, joining with other European Union states in placing sanctions on various members of its government.

In the longer term, the disputed sovereignty of the Falkland Islands has been a thorny aspect of relations with Argentina and the broader region, though there has been an appreciable effort made by both sides to build greater engagement both on and around this issue. One visible and highly significant aspect of this engagement was a joint humanitarian project, led by the International Committee of the Red Cross, that in 2017 was able to identify the remains of over 100 Argentine soldiers killed during the 1982 conflict.

Alongside the UK’s diplomatic efforts in the region, the UK has done much to enhance its soft power – broadly defined as power of attraction – and the impact of this can be felt in areas as diverse as education, trade, values, and trust. Data on perceptions of the UK from the Latin American G20 countries (Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina) show that the country remains highly attractive to Latin Americans, particularly citizens of Mexico. This attractiveness, however, is not reciprocal, as people in the UK tend to view Latin America more negatively than they do most other G20 countries.

Security and defence

The UK’s relationship with Latin America presents defence and security priorities that are distinct from those concerning other parts of the world. The absence of nuclear weapons and the region’s relatively low terrorist threat to the UK, for instance, have tended to mean that Latin America has not been top of the list in terms of UK defence and security priorities, as is clear when we analyse major strategy papers published by the UK government over the last eight years.

There do exist, however, other serious and specific challenges, not least transnational organised crime, peacekeeping, and the illegal drug trade. Engagement in these areas is indeed considered priority, as evidenced by the UK’s Defence Cooperation treaty with Brazil and its close relations with Colombia on issues such as peacekeeping and the cocaine trade.

Strengthening the UK’s relationship with Latin America and the Caribbean

In order for the UK to make the most of the opportunities available, it needs first of all to move away from outdated perceptions of the region. Aside from being inaccurate, such perceptions contrast unfavourably with the positive light in which the UK is viewed by Latin America, where many countries well remember and well regard shared histories that have been somewhat neglected in the UK.

This “attractiveness gap” is one of the key areas for the government and other actors to tackle. There is a case to be made for working directly with Latin American states to help them promote the benefits that their countries could offer to UK citizens. Though this would entail a degree of promotion of third countries, mutual potential gains mean that this could nonetheless provide a net benefit to the UK: narrowing the attractiveness gap and promoting domestically the opportunities available in the region could in turn provide a real boost to commercial and cultural engagement. The Department for International Trade in particular is already working to make opportunities more visible in the UK, as well as putting in place a solid framework to support companies from both the UK and Latin America as they seek to do business.

Another recommendation highlighted in the British Foreign Policy Group’s report relates to governance of the UK-Latin America relationship. It recommends a more coordinated policy across Whitehall, with stronger engagement of regions and devolved institutions to help other nations and geographical areas get the most out of the UK’s increased engagement with Latin America.

As it withdraws from the European Union, the UK will also be looking to build on existing trade links around the world as part of a wider strategy of global engagement. The trade continuity agreement signed in January 2019 between the UK and Chile is a promising sign of shared intention first to maintain and then to boost commercial ties with the region more broadly.

All in all, there exists a longstanding shared desire to forge a flourishing relationship between the UK and the diverse countries of Latin America. Combined with the UK’s renewed global engagement, the clear potential for significant mutual benefits could finally be realised.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article draws on the report Revitalising UK-Latin America Engagement post-Brexit (2018)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting