One hundred years on from her birth in May 1919, Sonia Gomes (LSE Library) looks back at the life of Dominica’s first female prime minister Eugenia Charles, from her time studying law at LSE in post-war London to her return to the Caribbean, the beginnings of her legal practice, and her ultimate rise to national and international prominence.

One hundred years on from her birth in May 1919, Sonia Gomes (LSE Library) looks back at the life of Dominica’s first female prime minister Eugenia Charles, from her time studying law at LSE in post-war London to her return to the Caribbean, the beginnings of her legal practice, and her ultimate rise to national and international prominence.

Mary Eugenia Charles was the youngest of four, born on the Caribbean island of Dominica in 1919. She was thought of as the troublesome child. Her first battle with the authorities happened at the age of four, on her first day in school, when she refused to sit in her assigned seat for wanting to sit next to her playmate. She screamed the place down until allowed to do just that.

It was this lifelong determination that enabled her to become the first female lawyer in Dominica, the first and only female prime minister in Dominica (as well as the second in the Caribbean), the longest serving prime minister in Dominica’s history, and the third longest serving female prime minister anywhere in the world. Quite a few notable firsts, particularly as the centenary of her birth roughly coincides with the centenary of (some) women’s suffrage in the UK.

Eugenia Charles at LSE

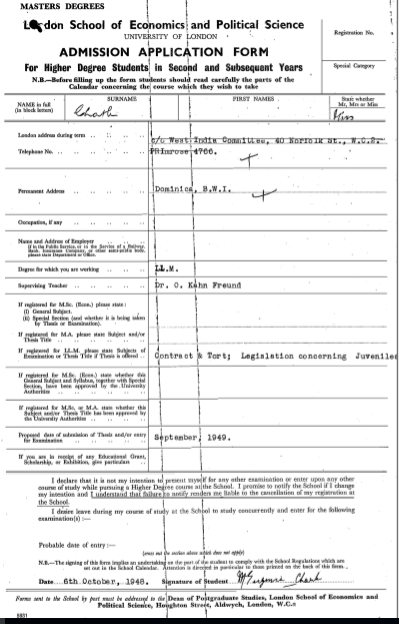

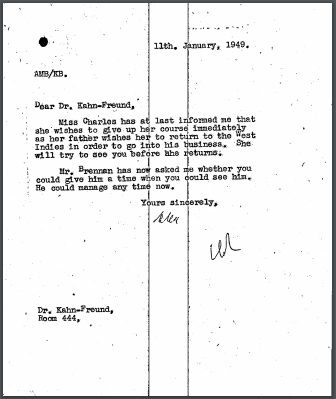

Charles’ LSE student files contain little about her time here. We have documents confirming her registration, class attendance, and her withdrawal from the course in 1949. Eugenia came to LSE to sit for her final examinations at the Inns of Court and be called to the Bar at the Inner Temple. Whilst doing it, she’d decided to take up a couple of law courses at LSE.

Charles came to London in 1946, a time of austerity as well as a time of new beginnings. London was hosting a number of events that had been postponed for years due to the war. The Ideal Home Exhibition was back and so were the Olympic Games. London was also celebrating the Royal Wedding. Eugenia Charles made the most of it and attended all of these and many other events that came her way, as her account of a 1948 New Year’s party tells us.

“Boy did I enjoy that and did I let myself go (…) A fellow barrister of mine told me that he thinks I let down the profession by the amount of jiving. But I didn’t care. I told him for after all when I get down to Carnival at home I will do a lot more than that.”

Charles’ supervising teacher at LSE was Dr Kahn-Freund, a scholar in British Labour Law. She seems to have impressed him as his remarks about Eugenia are positive and constructive, as opposed to Dr Potter who wrote “(she) is not able to contribute much and is irregular in attendance – does not seem particularly interested”. Potter instructed Charles in tort law, whereas her contract law teacher was Dr Glanville-Williams, whose work is still considered essential reading for law students.

She studied for six days a week and also worked as a radio journalist for the BBC’s World Service. Her job was to prepare and deliver a four-minute Caribbean news programme for which she went to parliament to listen to discussions about the affairs of the Commonwealth. A useful experience for when she entered politics.

Despite missing sessions and being quiet in class, Charles was very happy with LSE. She liked the School being at the centre of all hustle and bustle and loved LSE’s well-stocked library, which at the time offered ten reading rooms and a speedy book retrieval system, “No time wasted Kid”, she wrote to a friend describing the library.

However, the British weather got the better of her. She wrote to her parents “I don’t know if I’ll be able to stand this weather and country this winter”, and they came to her rescue. Together they enjoyed the London Summer Olympics and travelled around Europe before returning to Dominica.

Returning to Dominica

Once back in Dominica, Charles set up her legal practice and made herself busy with the family businesses until getting into politics. It was in response to the so-called “shut your mouth” bill (1968), which looked to crack down on opposition criticism, that Charles found the Dominica Freedom Party.

Charles led her party into parliament in 1980 on the strength of her arguments around Dominica’s independence. She focused on the need for a referendum to give the country a chance to decide on the terms of such a big step. She said:

“There must be a referendum … live discussion in all parts of the island, in all walks of life and in all classes. … People must know what it is going to be, … and they must accept it with their eyes wide open”.

Charles found that speaking in the House of Assembly was what made her tick, more so than arguing in a courtroom, and she made the most of it. She made the most of her sense of humour too.

Once, when the government of the day decided to impose a new parliamentary dress code and forgot to include requirements for women, Eugenia jumped at the opportunity to mock the opposition. She arrived in parliament wearing her long black barrister’s robe over a bathing suit. As the parliamentary session began, Charles took off the cloak and proceeded as if beachwear was the natural choice for the occasion, leaving everyone in stitches.

It was because of decisions like this that Eugenia’s actions tended to catch people by surprise. No one saw it coming when she controversially invited the US to invade Grenada in 1983 (see video above), nor did anyone think her able to survive the constant misogynistic attacks by her opponents. However, she ended up running the country for 15 years (1980–1995) and was made a dame four years before retiring from politics.

During her retirement, Dame Charles continued to work around the world promoting human rights and democracy, becoming also a co-founder of the Council of Women Leaders. To many abroad she was the “Iron Lady of the Caribbean”, but at home she was simply Mamo, the affectionate term for leader.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This article is a slightly modified version of an earlier post on the LSE History blog

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Grateful for this essay on Dame.Charles’ time at LSE. She made a meaningful contribution to our homeland Dominica and the world.

GJC

Indeed, I dare say, that our Dame Eugenia Charles was a force to be reckoned with.

Her remarkable contribution and success but not without challenges and failures shape the landscape of our beautiful country the Commonwealth of Dominica. Mamo, as she was affectionately called was and inspirational and formidable woman Prime minister.

Johanna Isidore

I had the opportunity to work with Dame Eugenia as a young senator in her government at only 21. I admired her leadership style and her very caring attitude. She was a no nonsense woman but had a very big heart and would give to any and everyone. I owe my love for politics and my success in part to this iron woman better known as MAMO. Her legacy will live on and I intend to make sure she is remembered as the savior of Dominica. May her soul RIEP.