Conventional wisdom sees economic anxiety as central to the rise of the far-right around the world, yet Brazil last year elected Jair Bolsonaro despite impressive results in terms of growth, poverty, and wage disparities in the 2000s. Essentially, the Rousseff years failed to address falling competitiveness in manufacturing, inflation in services, and a distributive conflict affecting those on middle incomes, while an increase in debt-to-GDP allowed the subsequent crisis to be blamed on fiscal profligacy. Cuts in public expenditures then combined with external factors to slow any recovery, and Bolsonaro found electoral success by linking economic stagnation to corruption amongst the entire political establishment. But Bolsonaro’s response has been disastrous, and its disappointing results could prove to be his undoing, writes Laura Carvalho (University of Sao Paulo).

Conventional wisdom sees economic anxiety as central to the rise of the far-right around the world, yet Brazil last year elected Jair Bolsonaro despite impressive results in terms of growth, poverty, and wage disparities in the 2000s. Essentially, the Rousseff years failed to address falling competitiveness in manufacturing, inflation in services, and a distributive conflict affecting those on middle incomes, while an increase in debt-to-GDP allowed the subsequent crisis to be blamed on fiscal profligacy. Cuts in public expenditures then combined with external factors to slow any recovery, and Bolsonaro found electoral success by linking economic stagnation to corruption amongst the entire political establishment. But Bolsonaro’s response has been disastrous, and its disappointing results could prove to be his undoing, writes Laura Carvalho (University of Sao Paulo).

• Também disponível em português

• Disponible también en español

Recent polling by IGM Chicago suggests that there is strong agreement amongst European economic experts that “rising inequality is straining the health of liberal democracy” and that “enacting more redistributive expenditures and policies would be likely to limit the rise of populism in Europe”. Indeed, from threats to democratic capitalism posed by the decline of the middle class in Branko Milanovic’s Global Inequality to the role of austerity in explaining support for Brexit in a recent empirical paper by Thiemo Fetzer, the topic has become increasingly important across various strands of economic literature.

When it comes to the specific role of globalisation, Dani Rodrik has tried to understand how different shocks give rise to left-wing (economic) populism or to right-wing (cultural) populism, depending on the particular societal cleavages highlighted by politicians. While trade liberalisation and immigration might set the stage for an emphasis on identity cleavages, as in Europe or the United States, financial liberalisation would tend to lay the ground for a focus on income cleavages, as in Southern Europe or Latin America.

But then we have Brazil, a commodity-exporting economy that benefited greatly from Chinese growth in the 2000s and earned widespread recognition for reducing poverty and wage disparities through redistributive policies. If we accept the conventional wisdom on the role of economic anxiety in the rise of the far-right, how are we to understand the election of Bolsonaro in 2018?

From boom to chaos: Brazil’s economic meltdown

Like many other Latin American economies, Brazil took advantage of the commodity-price boom of the 2000s to expand government spending in health, education, infrastructure, and social protection, yet it still managed to reduce its public debt-to-GDP ratio during Lula’s administrations. The higher growth rates of both consumption and investment between 2006 and 2010, which represented a rapid recovery from the Global Financial Crisis, were accompanied by strong job creation in the construction and service sectors, as well as by impressive wage gains for low-skilled workers.

The expansion of the cash transfer program Bolsa Família – from 3.6 million recipients in 2004 to 12.8 million in 2010 – and the rise in real minimum wages of 5.9 per cent per year during this period also helped to increase the meagre share of national income accruing to the bottom 50 per cent from 12.9 per cent in 2004 to 14.3 per cent in 2014.

But by the time Brazil reached its highest real GDP growth rate during that period – 7.5 per cent in 2010 – the economy was already facing difficult challenges.

First, the country’s manufacturing sector, which had been losing density since trade liberalisation in the 1990s, was losing additional competitiveness due to a strong currency appreciation and the higher penetration of Chinese imports after the Global Financial Crisis.

Second, higher wage growth was leading to an acceleration in services inflation, which meant high interest rates needed to be maintained in order to attract foreign capital, further appreciate the currency, and suppress inflation of tradable goods.

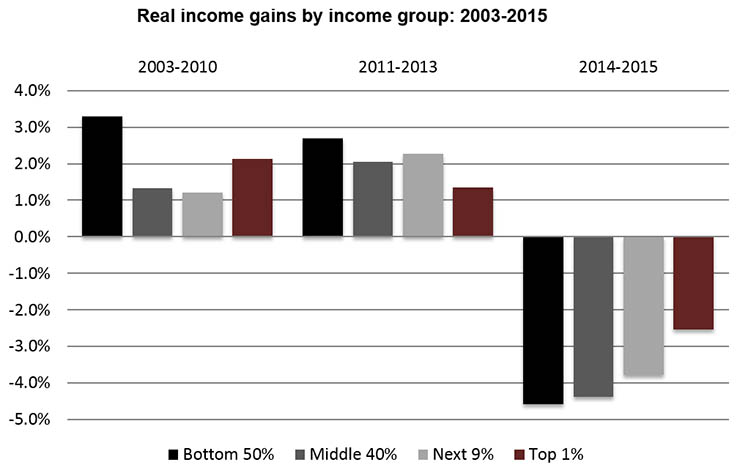

Third, a distributive conflict was becoming apparent, as the reduction of inequality was due to a fall in the share of income going to the middle of the distribution, with the bottom 50 per cent and the top one per cent experiencing the strongest gains (as illustrated below).

When Dilma Rousseff took office in 2011, the plan was to address the lack of competitiveness in Brazilian manufacturing through a real depreciation of the exchange rate and various measures aimed at reducing the cost of production, including tax exemptions and controls on energy tariffs. As the external scenario deteriorated – with the end of the commodity-price boom and the European periphery crisis – this set of measures proved highly ineffective in boosting the country’s exports and preventing an economic slowdown.

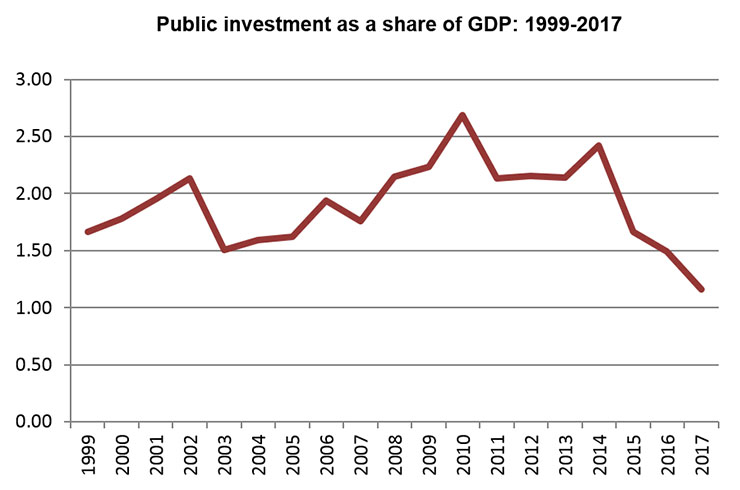

Moreover, when combined with the slower growth of tax revenues caused by the economic slowdown, the high cost of these subsidies contributed to a deterioration of the fiscal stance. While public investment, which had grown 27.6 per cent per year in real terms during the boom period of 2006-2010, remained almost stagnant in 2011-2014 (illustrated below), the increase in public debt relative to GDP in 2014 allowed for a dominant view to be built around the idea that the crisis was caused by the government’s fiscal profligacy.

Austerity, inequality, and Bolsonaro’s election

Since then, many of the same problems facing the Western world seem to have converged on Brazil, only starting with a far higher level of social vulnerability.

The economic agenda has focused almost exclusively on cutting public expenditures. With a sharp drop in oil prices – from $85 per barrel in late 2014 to $25 in early 2016 – hitting the balance sheet of the Brazilian oil company Petrobras and the rest of the economy, the government reduced federal investment by more than 35 per cent in 2015. At the same time, the Central Bank raised interest rates in response to an inflation acceleration, which was mainly driven by a rapid adjustment in previously controlled energy tariffs and fuel prices.

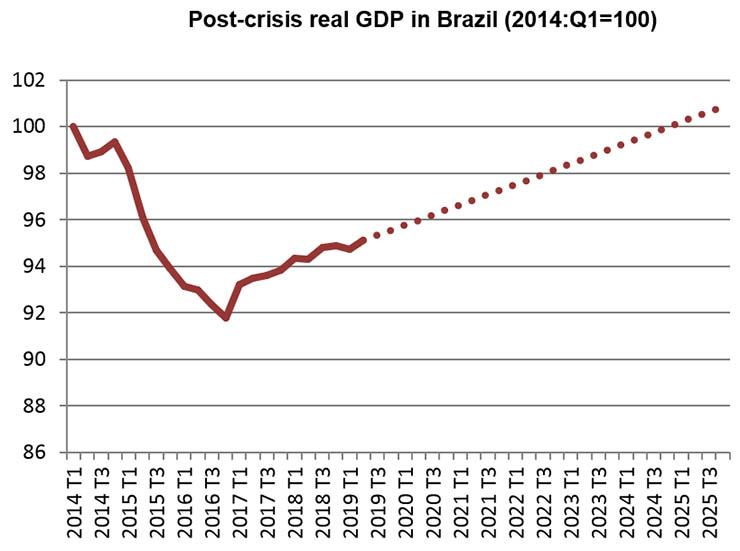

After a real GDP contraction of 8.2 per cent in 2015-16, the Brazilian economy has been going through the slowest economic recovery in its history. And this despite all the beautiful promises about a boost in investor confidence following the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff and the Congressional approval of a constitutional ten-year freeze on real federal spending. If the economy continues to grow at the same pace as it has since 2017, Brazil will only return to its pre-crisis real GDP level by 2025, more than ten years after the peak (as shown below).

Last year’s presidential elections thus occurred in a context of mounting frustration and economic anxiety: unemployment had doubled – from 6.5 million people in 2014 to 13.2 million in 2017 – and inequality was rising twice as fast as it had fallen in the 2000s.

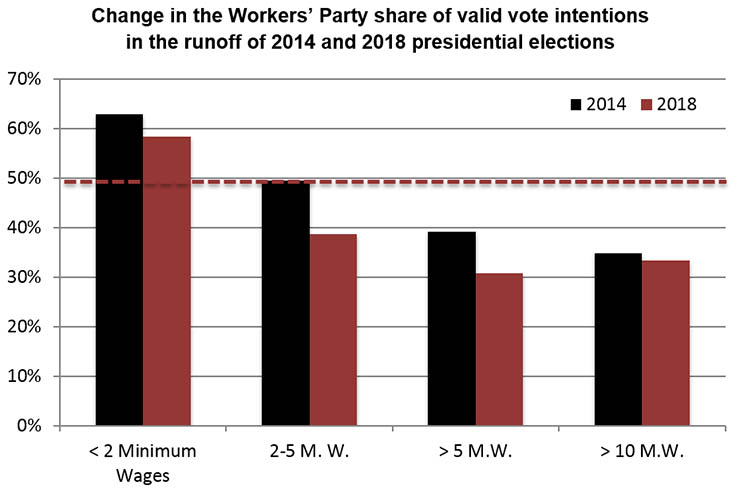

The Workers’ Party lost more votes between 2014 and 2018 among households with intermediate levels of income (illustrated below). These are precisely the groups that did not benefit so much from the boom but did suffer significant losses during the crisis, as has been argued by Amory Gethin and Marc Morgan.

To make matters worse, the crisis period coincided with the largest corruption investigation in Brazilian history (known as Lava Jato, or Operation Carwash), which facilitated the simplistic yet understandable perception amongst the general population that corruption itself was the cause of the economic meltdown. Rather than blaming immigrants or Chinese manufacturers, responsibility for the economic slowdown was attributed entirely to the political establishment and the left.

From this perspective, it becomes easier to understand how, in contrast to other far-right candidacies around the world, Bolsonaro was elected through the combination of his well-known morally conservative discourse and an ultra-liberal economic platform: getting rid of a corrupt state in all areas (except public security) was sold as a solution to all of the country’s problems.

What remains to be seen is whether the disastrous results of Bolsonaro’s agenda for the vast majority of the population, who would clearly benefit from a strong labour market and still rely on public services and social safety nets, will also prove to be his downfall.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Excelente artigo! Lúcido, informativo, imparcial e compacto. Não se vê muito pela internet hoje em dia.

I think you’re expecting too much in so little time. The guy has only Been in this uphill fight for 9 months. Congress is not helping much and papers like the one you write for, attack him viciously 24/7.

There’s a lot to be done and we all should contribute to make Brazil a great country. I’m counting on you!

Dear Carlos,

In less than nine month Obama turned around the American (and world economy) . The fact is that Bolsonaro had no economic plan and starting with pension reform was the worst way to tackle Brazilian economic challenges. As a result more than 2300 industries went out of business since he took office.