The upsurge in state repression of recent protests in Chile has echoes of the Pinochet era, but so too does the role played by school students in resisting it and trying to build a fairer society, writes Richard Smith (University of Liverpool).

The upsurge in state repression of recent protests in Chile has echoes of the Pinochet era, but so too does the role played by school students in resisting it and trying to build a fairer society, writes Richard Smith (University of Liverpool).

On 6 October 2019, the price of a ride on Santiago’s metro system rose by 30 Chilean pesos to around £0.90 (US$1.15). In protest, groups of secondary school pupils began to jump the turnstiles, and before long this simple act of disobedience had exploded into mass fare evasions, widespread violence, arson, and looting, as well as a backlash of arrests, injuries, and fatalities.

But this sudden outpouring of discontent was never about rising public-transport fares. It is rooted in a longstanding dissatisfaction with the neoliberal transformation of the economy and the state that began under the Pinochet dictatorship in the 1970s and then continued under civilian-led governments from the 1990s onwards.

The current right-wing president, Sebastián Piñera, has proved unable to quell the unrest, while the appearance of armed troops on the streets and the violent actions of the carabineros (the militarised national police) has been distinctly and uncomfortably reminiscent of Pinochet’s barbaric rule.

But just as this upsurge in state repression echoes the Pinochet era, so too does the key role played by students and young activists in resisting it and trying to forge a fairer society.

Chilean school activism under Pinochet

That secondary school students provided the spark for Chile’s recent upheaval is particularly intriguing when you consider that 14- to 18-year-olds already pay a drastically reduced tariff on the metro. But this is less surprising when we consider Chile’s long history of young protesters taking resolute action to oppose government policy.

Back in the 1980s, teenage activists protested alongside university students, trade unions, church groups, and the youth of Santiago’s shantytowns. My own research fieldwork in Santiago, which involved interviews with numerous former activists from the secondary-school opposition movement of the 1980s, highlighted a great many parallels and contrasts.

First of all, many of the issues on which students campaigned in the 1980s revolved around schooling. In 1980, Pinochet’s government had begun the “municipalisation” of state education, handing control over schools to local councils, fragmenting the provision of publicly funded education, and increasing private-sector involvement. The climax of this process came in 1985 and coincided with a particularly militant period in the school students’ movement: the first of many pupil-driven school occupations occurred in July of the same year.

Part of the explanation for school-age activism in Chile relates to the country’s long tradition of elected course and year representatives, as well as the existence of a national federation of secondary school pupils. These institutions, which predated the 1973 coup, were ended by the military government in 1974.

For the activists that I interviewed, this kind of democratic representation was important, but so too were travel passes for public transport, the cost of university entrance tests, and properly funded public education. It was, however, the bigger picture that mattered most. They wanted to topple the dictatorship and bring in social justice based on respect for human rights and equality. They also wanted the freedom to go out at night and enjoy being young, as well as the liberty to study and develop unencumbered by an autocratic state.

The school students’ movement and the return to democracy

With the return of civilian-led government, secondary school students continued to use well organised and effective campaigns to oppose Pinochet-era reforms to state education. In 2001, the so-called “Mochilazo”, named for the ubiquitous mochilas (rucksacks) students used to carry their books to school, focused on the issue of bus and metro passes for schoolchildren. This was soon followed by the “Penguin Revolution” in 2006, named after pupils’ black and white uniforms, and then a series of mass marches throughout Chile in 2011. Like their predecessors in the 1980s, the school students involved in these protests demanded a better funded, higher quality, less fragmented public education system, along with constitutional reforms and free higher education.

Whereas post-dictatorship school protests have been coordinated by elected delegates, for students in the 1980s the first battle was to recover their right to democracy in schools. They achieved this first by subverting the undemocratic “designated” representatives introduced by military-appointed headteachers, managing instead to get themselves appointed to these posts. They then shadowed officially endorsed student bodies with their own clandestine “democratic committees” (CoDes) where members of political youth movements, whether young Christian Democrats to Young Communists, would work together to plan their actions.

The CoDes of the various schools would meet weekly in regional groups across Santiago to plan and coordinate actions, and the regional groups then re-established the umbrella national federation, which had been banned over ten years earlier. As in today’s protests, in the 1980s decisions were taken via mass democratic assemblies, though gatherings during the dictatorship implied severe time pressures because of the ever-present danger of discovery and arrest.

During the both the campaign to resist military rule and the Penguin Revolution in 2006, school occupations were an important tactic. Pupils would organise themselves into brigades to occupy a school, acquiring banners, leaflets, locks, chains, and spray-paint in advance. The “red” brigade would go in first to secure the building and to corral teachers into the staff room. The “black” brigade would take the roof, hang the banners, and organise the defence. “Green” would control the playgrounds, spraying slogans and scattering leaflets. Then as now, teenage activists displayed a capacity for organisation that would be the envy of many mainstream movements run by adults.

Another common tactic has been mass marching through central Santiago. One Pinochet-era militant described how school students would close off Santiago’s principal avenues by blocking traffic at a junction and then walking slowly with their banners while chanting slogans, conscious that they had only around seven minutes before the carabineros would show up. After fleeing they would reconvene a few blocks further down the street and then repeat the process.

In the 1980s, protesting posed a number of serious risks for young people: violence from right-wing students, beatings from police, and even possible torture and disappearance by security forces. This is why the recent return of open repression on the streets of Chile, with water cannons spraying peaceful demonstrators and tear gas being dispersed at will, struck such a chord with the public. As one local put it to me:

When night falls and the helicopters fly and the curfews return, all accompanied by an incessant soundtrack of people banging on pots and pans, the memories also return, and as they do they bring on a mix of emotions: fear, joy, doubt.

The Chilean school student movement in 2019

In 2019, violence has returned to the classroom, presaging and laying the foundations for Chile’s recent unrest.

Students, particularly those from emblematic state schools like Instituto Nacional in central Santiago, have campaigned against the introduction of new measures that they see as indiscriminately criminalising youth, not least the “safe classroom” law that makes it easier to expel pupils and reinforces stop-and-search powers for teenagers over the age of 14. This year has seen a student strike, Molotov cocktails at school, and carabineros launching tear gas into classrooms. The students jumping the turnstiles of the metro did not emerge from nowhere. The latest protests came after a fractious winter in which they opposed government attempts to restrict their ability to protest, a campaign which itself received a robust response from the state.

Overall, in the 1980s, the 2000s, and again this year, secondary school students have campaigned for basic rights and constitutional change while fighting against neoliberal policies and reforms. In response, the state has deployed differing levels of violence and intimidation. By opposing the unequal society bequeathed to them by the Pinochet regime, the students who kickstarted today’s protests are building on the legacy of their forebears in 2001, 2006 and 2011, as well as reviving the traditions and tactics of their predecessors in the 1980s, who risked everything to oppose military rule.

As the popular slogan of the moment has it, it’s not about a thirty-peso rise in metro fares, it’s about thirty years living with the legacy of the Pinochet era. Over that time, no one has done more to press for change than the organised and committed protesters of Chile’s secondary schools.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

This article adds important historical context to the student led aspects of the current crisis. Thank you for posting!

Excellent article!

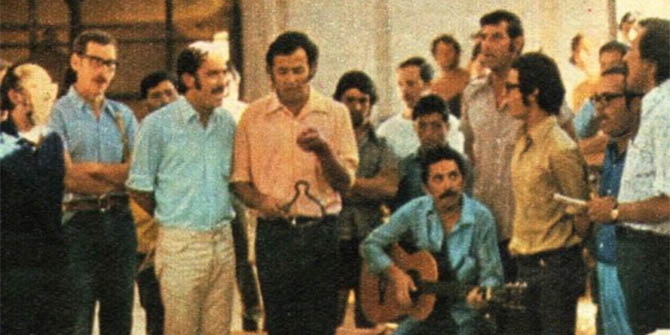

Glorious Liceo 7 de Niñas de Providencia in the picture. Chile say no more to this human destruction system called neoliberalism