Newly accessible public spending data reveal that Mexico’s federal bodies tend to spend on communications, publicity, and advertising in a highly irregular manner, with a huge skew towards the end of the year, and especially a “Christmas binge” in December. For the state, this extreme form of the “spend it or lose it” approach encourages lower-quality spending and hampers due diligence in procurement. Meanwhile, specific and sometimes vulnerable populations are left worse informed and protected than they could be, and proper journalistic scrutiny of government is disincentivised by media dependence on last-minute state publicity splurges, write Joseph Brandim Howson (University of Cambridge) and David Jáuregui.

Newly accessible public spending data reveal that Mexico’s federal bodies tend to spend on communications, publicity, and advertising in a highly irregular manner, with a huge skew towards the end of the year, and especially a “Christmas binge” in December. For the state, this extreme form of the “spend it or lose it” approach encourages lower-quality spending and hampers due diligence in procurement. Meanwhile, specific and sometimes vulnerable populations are left worse informed and protected than they could be, and proper journalistic scrutiny of government is disincentivised by media dependence on last-minute state publicity splurges, write Joseph Brandim Howson (University of Cambridge) and David Jáuregui.

One of the key legacies of the presidency of Mexico’s Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-18) was a clear new direction in public spending on social communications, official publicity, and advertising. Peña Nieto oversaw a massive increase in the allocation of resources to these activities, far outspending any of his predecessors.

As the industry cashed in on increased state spending, the pages and screens of Mexican media overflowed with government-led campaigns whose ostensible objective was to inform and defend Mexican society. By the end of his six-year term, however, these efforts had turned towards redeeming his tarnished image in the eyes of domestic audiences.

Transparency and media spending

Though it was quite clear that increasing sums of public money were being spent on publicity, for a long time it was unclear exactly how this spending was taking place. However, thanks to the efforts of organisations such as Fundar and Article 19, who have pushed for better access to data in this area, analysis of media spending has recently become possible.

Here, we employ self-reported data relating to publicity services contracted by 181 federal entities from 2013 to 2018, as published by the Secretariat of the Civil Service. Though there were inevitably errors and gaps that necessitated a data-cleansing process and a multi-stage analysis, this dataset does provide a new and uniquely detailed window into previously obscure patterns of publicity spending.

The Christmas binge

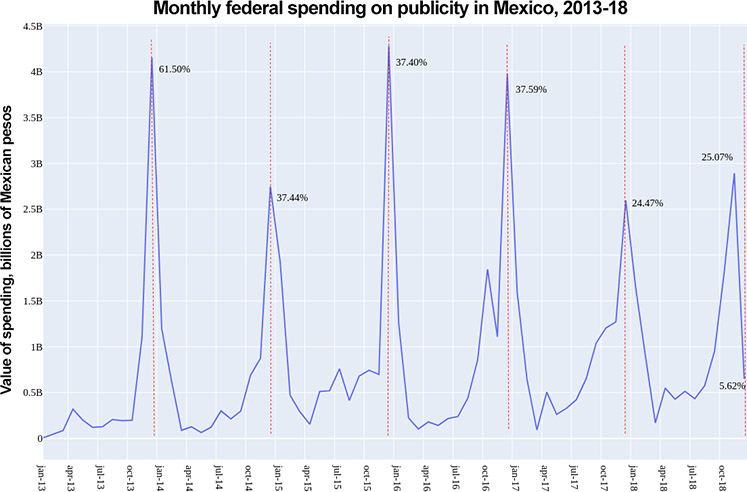

The clearest revelation emerging from the data is that publicity spending between 2013 and 2018 was heavily concentrated towards the end of each year. If a given institution’s annual budget were to be divided evenly across the twelve calendar months, we might expect roughly 8.3 per cent to be spent each month.

But looking at federal bodies in Mexico reveals that collectively these institutions managed to spend as much as 60 per cent of their annual publicity budget in one month alone: December. This particular high-point came in 2013, the first year of Peña Nieto’s presidency, but between 2013 and 2018 the average spend in December represented 34 per cent of the annual total. In other words, one in every three pesos spent on publicity during this six-year period was spent in December.

The one exception to this pattern was December 2018, when monthly spend on publicity fell below six per cent. Notably, however, Enrique Peña Nieto left office just the month before, when spending rose sharply to 25 per cent.

Moreover, if we look at the data at the level of individual federal bodies, we see this pattern taken to the extreme. In at least one of the six years covered, 36 of 181 federal entities did their entire year’s publicity spending solely in December. Widening the search parameters to bodies that spent 80 per cent or more during November or December, the number jumps to 91. That means that just over half of all federal bodies in Mexico participated in this extreme Christmas binge on publicity.

The Christmas gift that keeps on giving?

Most public policy analysts would not be surprised to see an increase in spending towards the end of the fiscal year, as the fear of future budget cuts drives this kind of spending pattern the world over. But Mexico’s Christmas binge is more than a mere blip in publicity spending. It is a surge, with entire budgets being spent at the very end of the cycle.

The broader “spend it or lose it” approach is generally considered to encourage lower-quality spending and hamper due diligence, both of which are central concerns when it comes to public expenditure. Being vastly more extreme, Mexico’s Christmas publicity thus becomes a serious cause for worry, particularly in terms of public procurement.

First, many of the entities that tend towards a Christmas binge also rely on effective publicity to fulfil their public mission. The National Commission for the Prevention & Eradication of Violence Against Women (CONAVIM), for example, did 100 per cent of its annual publicity spending in December 2013, December 2014, and November 2018. In December 2014, this meant over a million US dollars was spent in one month, with all of the awarded contracts going to a single media company. Other bodies with similar social functions, such as the National Centre for the Prevention & Control of HIV/AIDS (CENSIDA) and the National Institute of Ecology & Climate Change (INECC), display the same extreme pattern of spending.

Yet for all of these bodies, interaction with their target audiences would normally be required throughout the year, with different campaigns across different media tailored to the changes in the circumstances of these populations. Contracting publicity services in the final month of the year, with a single provider, seems unlikely to ensure the best possible service to the public. In these cases, it seems that vulnerable populations are being underserved due to the Christmas binge.

Second, though annual plans are usually outlined in January, many of these public bodies are not procuring publicity services until the very end of the cycle. The PR and media industry that emerged on the back of this boom in government spending is also left in a precarious position as their viability can easily depend on this flood of end-of-year contracts. This in turn puts providers of publicity services in a weak position, making them vulnerable to leverage from federal bodies. Holding out the promise of last-minute lucrative contracts as a “carrot” for Santa’s reindeer, federal entities can effectively discourage potential contractors from engaging in critical activities throughout the the rest of the year, be that by soft-pedalling on investigative journalism, changing editorial lines in newsrooms, or letting critical voices drift into economic uncertainty.

This potent combination of erratic spending and large public contracts has led to the co-optation of parts of Mexico’s media universe. Well-known newspapers like La Jornada can now be kept afloat by public publicity contracts, whereas economic insecurity contributes to two in every three journalists self-censoring their work.

Achieving a healthier pattern of publicity spending

The key means of regulating publicity spending, the General Law on Social Communication, came into effect in January 2019 under new president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and there have also been updates to existing guidelines on the Registration and Authorisation of Communication and Publicity. While both moves help to align Mexican regulation with international standards, they do not reverse or cap previous spending increases. Instead, they promote a new culture of transparency around publicity spending, particularly through new reporting mechanisms and stricter paper-trails that make it more difficult to engage in illicit activities.

However, their effectiveness when faced with a phenomenon like the Christmas binge is less obvious. Part of this push for greater transparency, Article 41 of the General Law on Social Communication, requires additional six-monthly reports on spending from every public body. Yet these reports are not required to compare planned spending to actual spending, to forecasts of future spending, or to budgeted resources for publicity in quarters three and four. Such measures would provide an early warning of uneven spending, and this would also come in time to intervene before December.

Guidelines are also sparse in terms of instructions on best practice, offering no advice on appropriate ranges of monthly publicity spending nor sanctions for consistently erratic spending. Neither do these interventions consider the possibility of rolling over unused funds into the following year, a method that has curbed “spend it or lose it” attitudes elsewhere.

Overall, the Christmas binge on publicity by Mexico’s federal institutions is bad news for wider society. In some cases, it means that specific and sometimes vulnerable populations are not being informed or protected as effectively as they could be. It also leaves the media beholden to federal entities in a way that can easily undermine public-service journalism.

Public policy has begun to catch up with the wider issue of increased public spending on publicity. However, phenomena like Mexico’s Christmas binge on publicity show that a more coordinated effort will be needed to tackle new problems in federal spending habits as they are revealed by improvements in public transparency and accountability.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This analysis emerged from the authors’ participation in the Publitón public-data marathon, which was organised by Fundar, Artículo 19, Social TIC, PODER, R3D, Censos, and Data Cívica; the authors would like to thank Fundar’s Paulina Castaño in particular for her insightful comments

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Great job done! Although I have some minor comments that does not discard or takes credibility out of the analysis I would like to say that this pattern is not exclusive of publicity. It is a phenomenon that occurs systematically. This problem is something that derives from the nature of the budget system, its execution, its reporting and the role of Congress (see the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Law). In any case is a great job and I would like to have access to the data or the report on a format that is useful for citation and more in depth analyses of course giving proper recognition and credit to the job done.

I lead a think to do tank in Mexico City particularly interested in these matters (fiscal policy and budgets, not publicity or government media), so it might be useful to share. Just ended a book on Presidents and Deputies in Mexico (1970-2018), happy to share.

Kind regards from CDMX,

Gabriel

Hi Gabriel, thank you for your feedback.

Yes, we imagine this pattern is seen in many other areas of public spending. Although the data we have analysed thus far has focused on publicity spending.

There are further methological details and a link to the data here: https://publicidadoficial.com.mx/el-gasto-navideno-en-publicidad-oficial/. We hope this is useful.

And do get in touch over Twitter if you’d like to discuss more (@Jaurevid, @J0_BH).

All the best,

David & Jo

Good job. Congratulations.

Thanks Marco, much appreciated.

Jo & David