The impact of COVID-19 will be more serious in Latin America than anywhere else in the world. To mitigate the damage and improve long-term prospects, the region needs to target a green recovery based on environmentally friendly growth and an expansion of renewable energy, writes Amir Lebdioui (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

The impact of COVID-19 will be more serious in Latin America than anywhere else in the world. To mitigate the damage and improve long-term prospects, the region needs to target a green recovery based on environmentally friendly growth and an expansion of renewable energy, writes Amir Lebdioui (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

• Disponible también en español

• Também disponível em português

The combination of COVID-19 and collapsing oil prices is expected to cause Latin American economies to contract by an average of 7.2% in 2020. Bouncing back from this massive shock will be no easy task. There is, however, a growing realisation that a return to the status quo will not be enough, and momentum is building towards the idea of “building back better”.

To date, most of the debate around the idea of a green recovery (and previously the Green New Deal) has taken place within a handful of advanced economies, with only minor exceptions like the “Pacto Ecosocial del Sur” emerging in the Latin American context. The irony is that Latin America has great need and great potential for a green recovery, not least because its rich legacy of development thinking has increasingly incorporated indigenous perspectives that promote development in harmony with nature (especially in Bolivia and Ecuador).

Why does the post-COVID recovery need to be green?

One crucial advantage of green recovery programmes is that they offer an opportunity to tackle several interrelated socioeconomic objectives at the same time: economic development, job creation, decarbonisation, and the kind of improved public health that also increases resilience to pandemics. In essence, green stimulus packages aim to address the so-called “triple crisis” of interrelated economic, social, and ecological problems by creating a vibrant, climate-resilient economy with broadly shared benefits for all.

Green stimulus programmes need to be prioritised for three main reasons:

- Environmental protection

Although the pandemic led indirectly to positive short-term environmental outcomes, several international organisations and experts have warned that this is no silver lining. Reduced greenhouse gas emissions were mostly due to temporary lockdowns, and levels of industrial production and fossil-fuel consumption will likely bounce back to pre-crisis levels just as they did after the 2008 financial crisis. Indeed, lower oil prices caused by falling demand could even encourage fossil-fuel consumption at the expense of renewable energy. Cars have also been favoured over public transportation as citizens seek to reduce contamination risks. Urgent action is needed if emissions are to be reduced sustainably in the long term. - Public health

COVID-19 has had an impact on the environment, but the environment also has an impact on pandemics. Energy transitions are a public health issue too, as they can generate long-term health benefits and bolster resilience to pandemics. The cleaner air associated with cleaner energy can help reduce COVID-19 deaths. Environmental degradation and climate change also contribute to the transmission of diseases from animals to humans. Building long-term resilience to pandemics will therefore require stricter environmental regulations. - Recovery rather than rescue

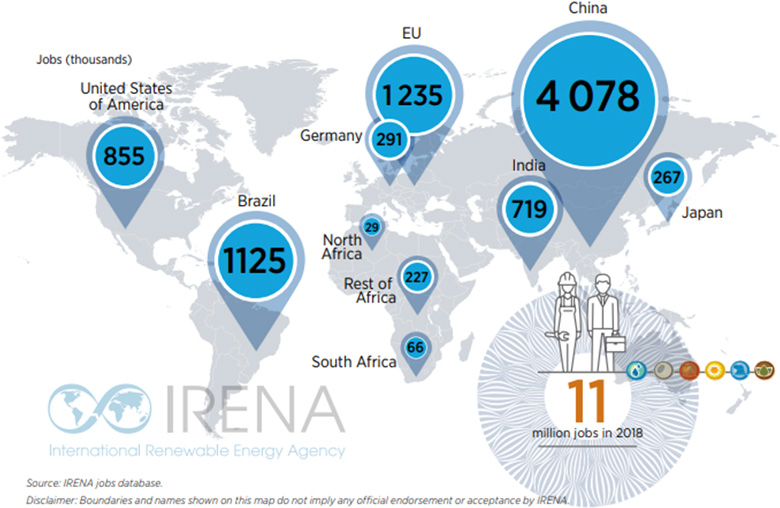

As emphasised by Lord Stern of LSE’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, a rescue without a recovery has no future. A return to funding “dirty” and “sunset” industries could easily create stranded assets, with sudden drop-offs in demand leaving these investments unprofitable and their workers unemployable. To guarantee decent jobs and job security, governments need to invest now in the jobs and skills of the future, with both the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the International Energy Agency already having demonstrated the tremendous potential for job creation in renewable energies (see below).

The business case for a green recovery in Latin America is also strong. A recent study by the Inter-American Development Bank revealed that Chile’s pension and sovereign wealth funds would have reaped even higher returns through green investing. The idea that there is always a trade-off between sustainability and financial returns is a fallacy.

In the post-COVID-19 context, stimulus packages provide an opportunity to leverage the socioeconomic benefits associated with energy transition, but relying on market forces alone won’t be enough. Recovery packages need to be anchored in forward-looking industrial policies. States have a key role to play in promoting the transformation of productive structures towards green industries. This is especially true of developing countries that lack pre-existing capabilities in these areas, where market forces may detract from welfare-optimal outcomes and where broader trends in anti-poverty and recovery policies have long favoured consumption jobs over production jobs.

Dr Amir Lebdioui makes the case for a green recovery from COVID-19 in Latin America

A recent IRENA report (to which I contributed) puts forward various industrial policies that can enhance local industrial capacities in renewable energy sectors. These include supplier-development programmes, fiscal incentives, price-control mechanisms, support for research and development (R&D; notably through long term patient capital), and improved education and training programmes.

Climate change and Latin American development

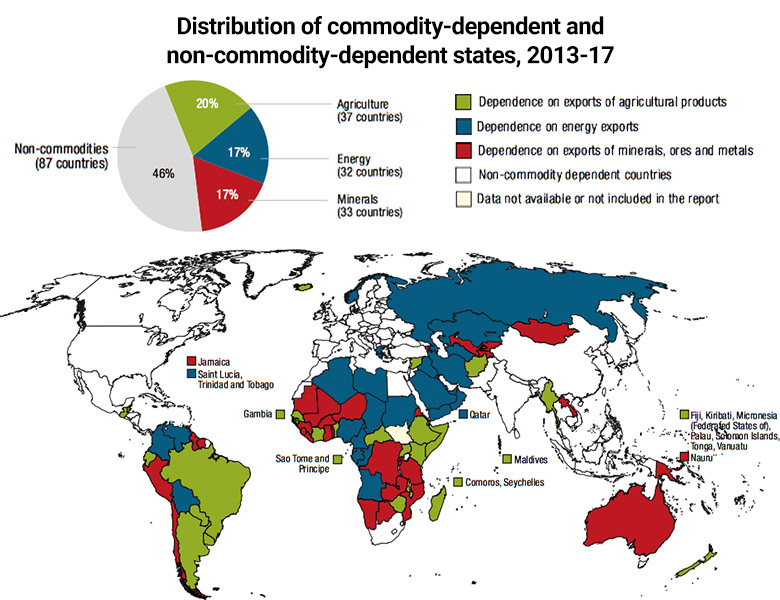

These issues are particularly crucial to the future of Latin America, because the region’s trade is intrinsically linked to climate change. Several Latin American countries are dependent on fossil fuels that are at risk of becoming stranded assets as the world decarbonises its economic systems. Outside of extractives, the region is also dependent on agro-commodities, where productivity is particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in temperature and precipitation. To note just a few obvious examples, climate change poses a serious risk to salmon farming in Chile, coffee in Colombia, and cacao in Ecuador.

In addition to the region’s direct productive vulnerability to climate change, Latin American firms will have to adapt as consumer demand shifts towards more sustainable products in key markets. The growing popularity of Green New Deal proposals in the United States and the European Union will inevitably bring regulatory changes that will reshape consumption patterns. Developing countries need to anticipate these “green” trade regulations and sustainability standards, shifting their productive capabilities towards export of green goods and services that will enjoy long-term access to the largest consumer markets.

The Latin American response so far

While Costa Rica has recently launched a “bioeconomy strategy” that seeks to address the challenge of COVID-19 via promotion of a green knowledge economy, most of the region’s responses to the crisis have seemed to look the other way, opting for fiscal austerity and increased environmental degradation.

In Brazil, the recent intensification of efforts to dismantle environmental protections came alongside a scaling back of environmental enforcement during the coronavirus outbreak. In Ecuador, the government has announced that it will cut the education budget in response to the pandemic; in the long term, this will have a negative impact on Ecuador’s accumulation of skilled human capital and therefore also its ability to upgrade into higher-value added activities.

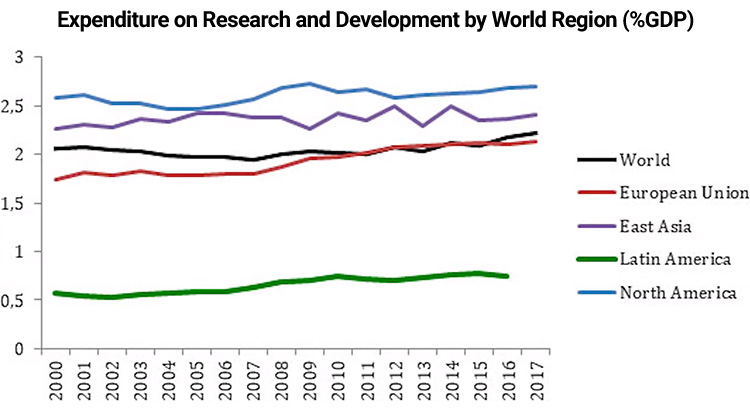

Such responses are simply unsustainable in the long run. A country’s ability to escape the middle-income trap largely depends on its ability to build innovative and productive capabilities, which requires skilled human capital and R&D support. The region’s average R&D expenditure (as a share of GDP) is already amongst the lowest in the world, falling well below the world average (see below). If they are to stimulate long-term growth, Latin American countries need more investment in human capital and R&D, not less.

This is also true of green R&D. In 2014, just four countries accounted for three quarters of the renewable energy patents filed worldwide: China, the United States, Japan, and Germany. The lagging share of spending on low-carbon R&D in developing regions (including Latin America) will have important implications for domestic firms’ ability to make best use of the window of technological opportunity provided by energy transitions.

Is a green stimulus risky or unrealistic?

Critics may argue that green industries are beyond the efficiency frontier of Latin American firms, or that policy interventions might be too costly. These kinds of ambitious programmes are also likely to face opposition from fossil-fuel lobbies and their domestic allies, meaning that governments favouring green transitions will need to be skilful in bringing broad alliances and state-business coalitions onside. And as with any industrial policy, there are indeed real risks and real challenges.

But we must never forget that the alternative to a green recovery programme is far riskier and more expensive, both in economic and in human terms. COVID-19 represents a devastating crisis for Latin America and the rest of the world, but recovering from it also provides a chance to take bold, drastic, and necessary steps towards greener development models.

The Canning House Forum is a new partnership between the LSE Latin American and Caribbean Centre and Canning House that aims to promote research and policy engagement around the overarching theme of “The Future of Latin America and the Caribbean”.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting