The 2016 Peace Agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia marked a fundamental milestone in terms of protections for the life and conditions of rural people. The numbers of homicides and deaths associated with the armed conflict decreased significantly during negotiations and immediately after the signing of the agreement. More recently, however, implementation issues and the presence of other armed actors have brought new threats for social leaders and vulnerable groups, often because of disputes over territory and resources. These threats have only become more acute during the COVID-19 crisis, write Carolina Castro (Universidad de los Andes), María del Pilar López Uribe (Universidad de los Andes), Fernando Posada (UCL Americas), Bhavani Castro (ACLED) and Roudabeh Kishi (ACLED).

• Disponible también en español

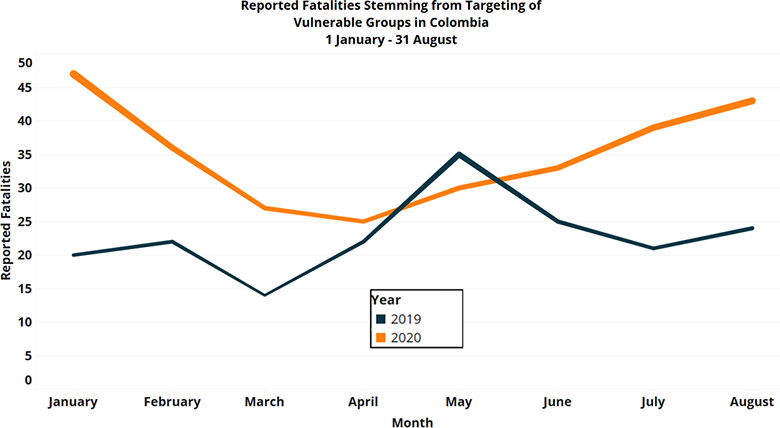

The killing of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups in Colombia has seen a dramatic rise in 2020. During the early part of the year, the number of killings was twice as high as during the same months of 2019. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and strict quarantine measures initially reduced this trend, leading to a slight decrease in killings. But as the coronavirus crisis became more normalised, a deterioration in the security situation of rural areas led to a new surge in the death toll.

Although different sources give somewhat different figures for the number of killings, overall trends are similar: there has been an alarming increase in the killings of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups in recent months, whether in comparison to the pre-pandemic period (January-March 2020) or to the previous year (April-August 2019).

Colombia’s stalled peace process and COVID-19

With little sign of progress on implementation of the Havana Agreement, many communities have lost confidence in the government and in state institutions. At the same time, risk factors for leaders supportive of the peace process have increased.

By committing to peace, leaders became the visible face of their communities. This in turn gave armed actors far more information about these leaders once the agreement was signed: where they were, which communities they represented, where they held influence, and how protected they were. This kind of knowledge aggravates the threat to their lives in general, but especially so during lockdown.

Several leaders found themselves isolated in their homes and communities, often without bodyguards or any other form of protection. This confinement has facilitated intimidation by armed groups, who are well aware of social leaders’ location and vulnerability.

Tracking the killing of social leaders

Data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) allows for the tracking of these trends. Given their very targeted and localised nature, killings of social leaders only tend to make international news or mainstream media when they build up to a tipping point. This makes it difficult for data projects relying on mainstream media to track these phenomena. For this reason, ACLED prioritises local media, supplementing this data with information from NGOs and local community networks. Over ten per cent of ACLED coverage comes from these types of sources.

In Colombia, this includes information from the Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (INDEPAZ), a Colombian NGO monitoring conflict in Colombia, as well as from Front Line Defenders, an ACLED partner that uses local networks to protect human rights defenders around the world. These non-media sources help to provide details on over a quarter of violent incidents against civilians in Colombia.

The events analysed here relate to social leaders and members of vulnerable communities, including farmers, indigenous people, and Afro-descendant people. This category also includes other groups which are frequently targeted, such as current and former members of the government, political parties, journalists, women, teachers, students, and LGBT people. In the context of the peace process, former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN) combatants who decided to reintegrate into society are also frequently targeted.

How have killings of social leaders changed during COVID-19?

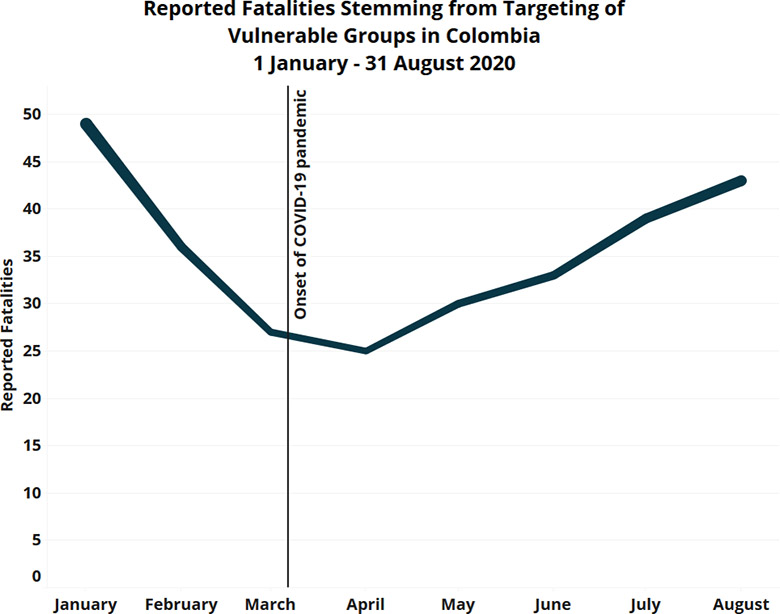

ACLED data indicate that in April 2020 there were an average of around six killings of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups reported each week. This average had increased to over ten per week by the end of August 2020, when the nationwide lockdown was lifted (see graph below).

A comparison with figures for the same period in 2019 further underlines the significant rise observed in 2020 (see graph below).

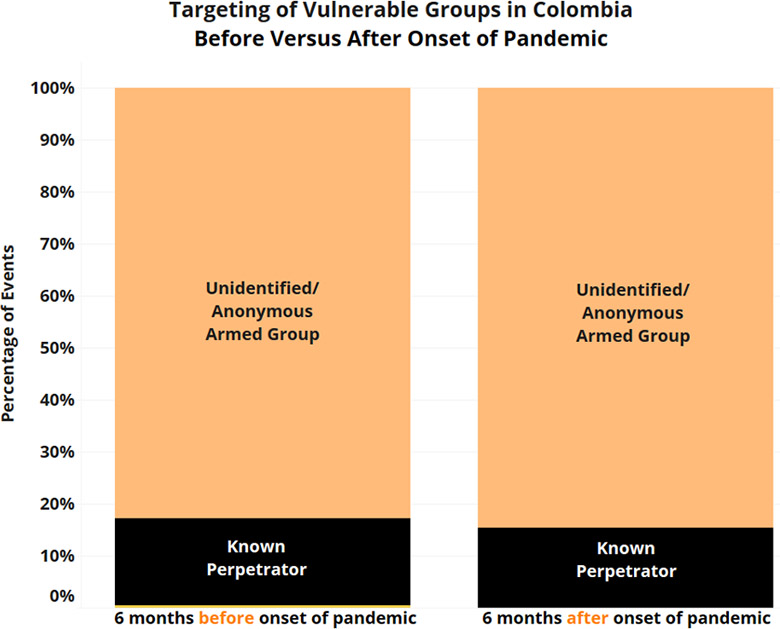

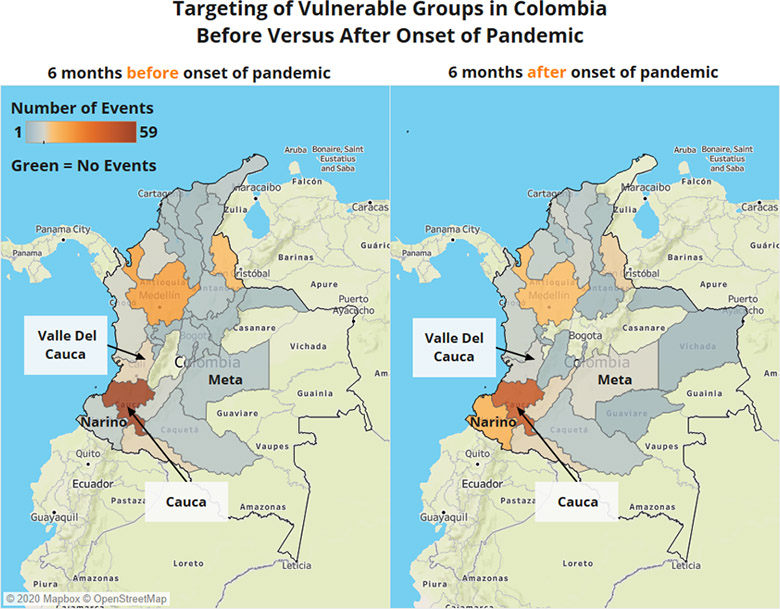

Although at the beginning of the strict lockdown there was a decrease in the killings of members of vulnerable communities, since May there has been a continuous rise in this trend. In the six months since the onset of the pandemic, the vast majority of attacks against vulnerable groups have been perpetrated by unidentified or anonymous armed groups, just as in the months prior to the pandemic (see graph below). That is, despite a recognition that increased violence against social leaders and vulnerable groups is a serious issue in Colombia’s post-conflict context, little effort has been made to uncover links between systematic killings and specific armed groups.

The exact reasons for the increase in the killings of social leaders and vulnerable groups is not yet clear, but analysts have largely centred on three explanations.

Three hypotheses on the killings of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups

The first hypothesis concerns links between the end of the armed conflict and disputes over territories considered abandoned by the FARC. Here, attacks are seen to be linked to implementation of the peace agreement and to disputes between armed groups as their strength waxes and wanes.

One of the consequences of this shift in power has been the emergence of new armed groups in disputed territories that aim to control drug trafficking and illegal mining, often attempting to recruit former FARC combatants to bolster their presence. More than 60 killings have also been attributed to FARC dissident groups themselves, and over 50 more to former paramilitary groups or international cartels.

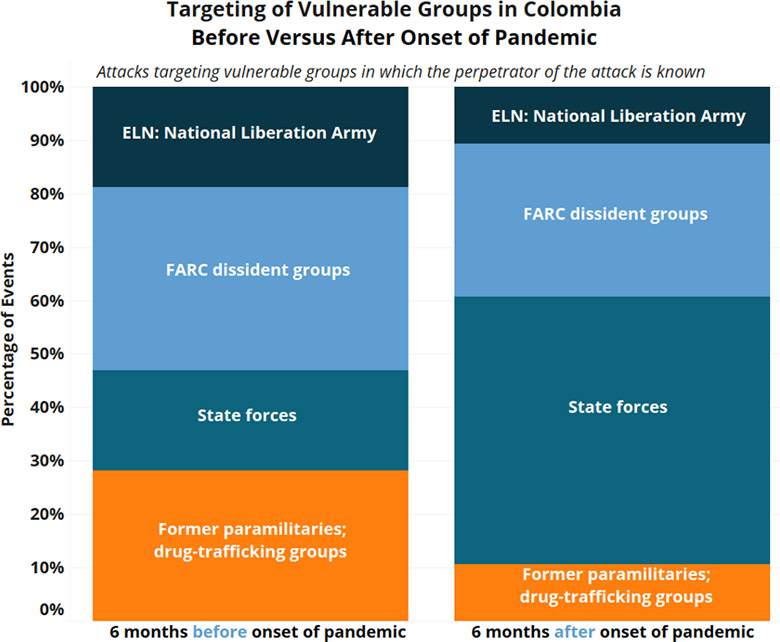

For events in which vulnerable groups are targeted by a known perpetrator, the participation of members of the armed forces is increasingly common: these cases represented 18 per cent of such attacks before the pandemic, rising to 50 per cent after its onset (illustrated by the teal-coloured section of the graph below). Most of these events are directly linked to military coca-eradication operations.

In the six months following the onset of the pandemic, nearly a third (28%) of attacks on vulnerable groups with a known perpetrator were perpetrated by FARC dissident groups (light blue in graph below), which is broadly similar to the trend prior to the onset of the pandemic.

A second hypothesis, meanwhile, relates to the vulnerability of rural inhabitants involved in government programmes that seek to curb drug trafficking. In 2019 and 2020, there were 16 reported killings of local leaders that were enrolled in coca-substitution programmes. The National Comprehensive Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS) provides funds to farmers and their families so that they can shift to legal crops, such as cocoa or coffee.

However, the state has also been engaging in eradication by military-led fumigation rather than focusing on voluntary programmes. By focusing on the weakest link in the chain of drug-trafficking activities – coca and marijuana farmers – the government exposes rural people to violence from the armed groups that make most of the profit from the business. And although most of these killings are perpetrated by illegal armed groups, some are linked directly to state-led eradication efforts.

The third and final common hypothesis concerns land disputes and environmental issues, both of which relate in turn to the previous two hypotheses. Essentially, the current process of land restitution in disputed territories puts at risk those farmers who are returning after having been displaced by conflict. In 2020, nine victims were part of the land-restitution process. Meanwhile, environmental leaders who fight against controversial construction projects and the exploitation of natural resources are made more vulnerable by rising tensions amongst the numerous armed groups vying for territorial control. According to the recent Defending Tomorrow report by the NGO Global Witness, Colombia ranks first in the world for killings of environmental leaders, with 64 reported deaths in 2019.

Alternative explanations: COVID-19, the economic crisis, and territorial control

In recent months, the public arena has been focused squarely on addressing the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic has absorbed the time, debate, and resources of the state and human rights NGOs, particularly through issues like restrictions on movement, public health, and the economic effects of quarantine. In the midst of a crisis that has disrupted the operations and priorities of state actors and NGOs, structural problems like systematic violence in rural areas have been pushed into the background.

Most public offices have been closed, blocking citizens’ access to the usual channels for reporting problems or seeking protection. Similarly, the activities of human rights NGOs have been severely limited by nationwide restrictions on movement, making it particularly hard to engage in fieldwork. The severe effects of the pandemic for vulnerable populations have in any case forced many NGOs to refocus their attention on more basic issues like food security and health.

Meta, for example, has more reintegraton areas than most departments, boasting three Territorial Spaces for Reintegration and Incorporation (ETCR). In the six months following the onset of the pandemic, five times as many events targeting vulnerable groups were reported in Meta than in the six months prior. Many of these incidents involve the killing of former FARC combatants living in reintegration camps. Analysts had already raised concerns about the government’s ability to guarantee the safety of former combatants living in the camps, especially as the temporary arrangements establishing these camps already expired without the government having released plans to turn them into permanent facilities or settlements.

Another aspect to consider is the lack of attention paid to the safety of social leaders in public discourse. Despite the fact that the situation of vulnerable groups in the country has deteriorated considerably in 2020, the issue has largely fallen out of public sight. News channels have instead begun to focus on COVID-19 and its impacts. Indeed, rural security issues, the protection of social leaders, and human rights violations have been displaced in public discourse by health and economic issues that have also significantly affected vulnerable populations.

As a result, communities living in remote areas are increasingly neglected from the national discussion, which only serves to isolate them further and to reinforce their vulnerability. Diminishing levels of information, research, and attention around this issue may also lead to weaker legal and social sanctions against armed actors that target vulnerable groups.

One indirect way to illustrate the decline in media attention is to analyse search trends on Google. These show a notable increase in searches related to the effects of the health crisis (on topics such as the economy and unemployment) and a decline in searches relating to human rights. As such, the onset of the pandemic and quarantine restrictions in Colombia has shifted the public’s focus on to the health crisis, leading to a decrease in protection and safeguards for vulnerable groups.

A second alternative hypothesis relates to the relationship between the pandemic and new opportunities for territorial control by non-state armed groups. Specifically, the coronavirus pandemic itself has sometimes been used as an excuse for armed groups to implement strategies of coercion and control in disputed territories. Armed groups enforced curfew and lockdown measures in at least 11 departments of Colombia, including long-troubled departments like Antioquia, Cauca, and Nariño. Dissident groups of the former FARC threatened to kill quarantine breakers in Cauca, while in Nariño measures were established by several groups, including dissident FARC combatants, the ELN, and the Gulf Clan.

Structural factors in Colombia’s southwest

Beyond pandemic-related explanations, structural issues have also contributed to a particular intensification of violence in the southwest of Colombia.

Nariño, for instance, is one of the main coca-production areas, principally because of its physical conditions and its access to the Pacific Coast and Ecuador, through which much of the product can be distributed to the United States and other international markets. According to local authorities, the killings taking place in Nariño can be attributed both to an increase in the local production of coca and to the escalation of a territorial dispute between the ELN and other armed groups that are exploiting the lack of state presence in the area. The ELN used to control several territories in Nariño, but its dominance has recently been challenged by the arrival in strategic areas of the Gulf Clan and different FARC dissident groups.

The increase in civilian targeting in Nariño can be seen in the maps below, which reflect a threefold increase in the targeting of social leaders in Nariño since the onset of the pandemic.

Beyond these hotspots, the targeting of vulnerable groups also expanded into Colombian departments that had not reported such problems in the lead-up to the pandemic, such as Guaviare, Vichada, and Tolima.

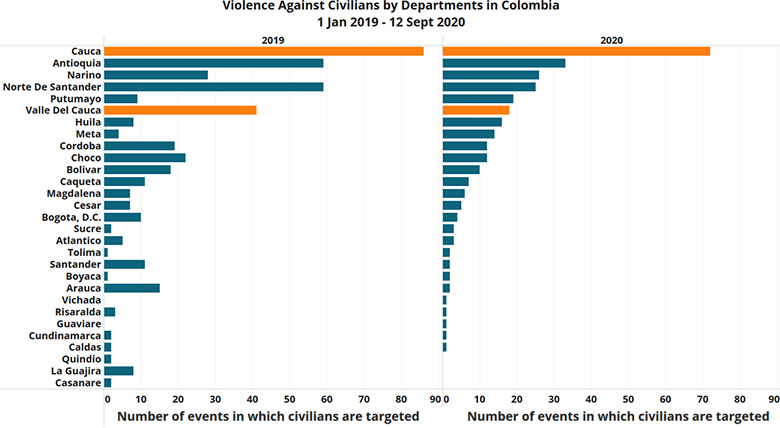

The departments of Cauca and Valle del Cauca (highlighted in orange below) have been hotspots of armed conflict since the emergence of the Cali Cartel, with high production of coca and good access to the Pacific Coast. In the northern area of Cauca, meanwhile, opposition to coca production amongst large indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities has made them increasingly vulnerable to attacks by different armed groups in the region.

The targeting of members of vulnerable groups in the Cauca region from January and August 2020 has been twice as intense as during the same period of 2019. While 54 members of vulnerable groups were reported killed from January to August 2019, the grim figure for the same period in 2020 was 101.

The absent state

This new wave of killings speaks to the tension and complexity of today’s Colombia, with historical, structural disputes aggravated by contestation over production of illicit crops, drug trafficking, and illegal mining. In the first instance, the state should be actively investigating these killings and bringing in measures that safeguard the rights of social leaders and vulnerable groups. In the longer term, these disputes will need to be addressed in a comprehensive, joined-up manner, with a renewed focus on the strongest actors in illicit production and distribution chains. This kind of integrated approach could at last help to protect those small farmers, indigenous people, and Afro-descendant communities whose defence of their lands too often costs them their lives.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Hey I did my masters on this just about to be published? I worked with unhchr staff in the field. It’s definitely got much worse