Using co-production and animation to explore the personal journeys of women who migrate from Colombia to Chile generates valuable methodological insights and a richer understanding of the process itself, writes Megan Ryburn (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

Using co-production and animation to explore the personal journeys of women who migrate from Colombia to Chile generates valuable methodological insights and a richer understanding of the process itself, writes Megan Ryburn (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

“For me, the sound would be marimbas and drums. There was so much music!”

“For me, the colour would be green because I was surrounded by nature”.

“For me, the smell would be the big bars of soap my mum used to use to clean our stilt house”.

These were some of the responses to the question “What sound, colour, and smell remind you of your childhood?”, which was one of the first things that we asked when we began co-producing the video Navigating borderlands: Colombian migrant women in Antofagasta, Chile in January 2020.

It was a bright, sunny morning in Antofagasta, in Chile’s northern Atacama Desert, and myself, the video’s designer Alice Volpi, and eleven women – the majority Afro-Colombian, from the Valle del Cauca, Colombia – had just finished coffee and biscuits before getting down to work. Even though the pandemic has since turned the world upside down, we have soldiered on in an effort to share the stories that we first intended to, seeing them as an essential part of wider conversations about migration and displacement.

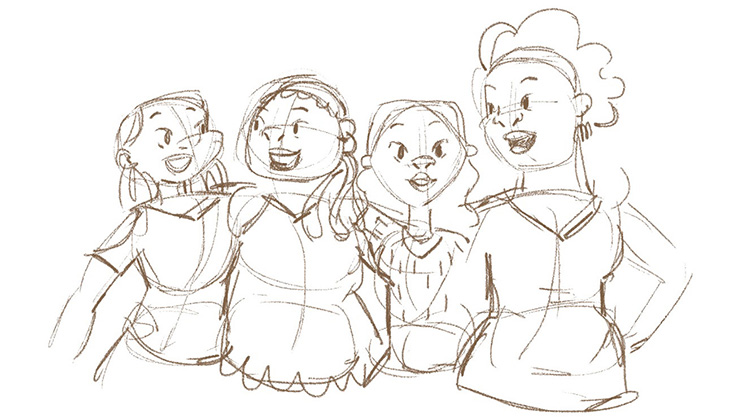

The animation focuses on four women as they navigate migration journeys from the Valle del Cauca, Colombia to Antofagasta, Chile. It balances the many hardships faced – poverty, violence against women, armed conflict, racism – with the determination and optimism that our co-producers embody and wanted to shine through. Though producing the video has taken longer than we originally planned, we have made something of which we are very proud, learning many useful lessons about arts-based research co-production along the way.

Choosing to go beyond text

The video is part of a wider research project addressing the cross-border lived experiences of Colombian migrant women in Antofagasta. An animated video was not one of the project’s initial intended outputs. Rather, it began to emerge on the last night of a fieldwork trip in 2019.

Magali, to use the pseudonym of one of the participants, invited me to her home in one of Antofagasta’s informal settlements for a final meal. After finishing the spread of patacones (fried plantain), rice, beans, and fried fish, she presented me with a lined notebook decorated with images of Colombian wildlife. “You can write my story in here so you can share it”, Magali said. It was one of the most beautiful gifts I have ever been given. It also gave me pause for thought.

As many of us do, I often think about issues of representation in research; about whose stories are silenced and whose are amplified; and about who is telling those stories.

Magali and the other women I work with unambiguously expressed both their desire to participate in my research, and their interest in having their stories told in written format. I am acutely aware, however, that the academic texts that I will produce are unlikely to be accessible to them. Moreover, they know and can tell their stories better than anyone else. Rather than seeing Magali’s gift necessarily as an invitation to write her story (although I also intend do that in a range of formats), I interpreted it as an invitation to collaborate and share her story with a wider audience.

Co-production, from start to finish

One of the principles of co-produced research is to include collaborators in the design from the outset. So, in conversation with Magali and two other women, we spoke about making an animated short video. Moving beyond text is a co-production tool that can improve inclusivity and reach, and an animated video seemed ideal. Using animation rather than “real life” filming also presented a practical workaround for issues of confidentiality and anonymity given the sensitive nature of some of the women’s stories.

In the end, once the animation was complete, nearly all of our co-producers asked to waive their anonymity and for their names to appear in the credits. I think, however, that was due in part to the use of animation, which made the stories more universal and prevented specific people from being linked with specific experiences. In the hands of someone as talented as our animator Alice, this proved to be an excellent medium for succinctly communicating complex concepts, emotions, and social realities.

Infrastructure as methodology

To co-produce the video, Magali, the other women, Alice, and I felt that the ideal approach would be to start by working collaboratively in Antofagasta. I was well aware that our co-producers have a multitude of employment and family responsibilities, and that it would be too much for them to give up more than two days of their time. Given that most of them work six or even seven days per week, it would also entail a loss of income, whichever days of the week we chose.

When co-producing research, it is fundamental to attend to these kinds of power relations, which are inevitably present in relationships between academic, artistic, and community co-producers. An important part of this is considering what David Bell and Kate Pahl have called “infrastructure as methodology“. This refers to often overlooked practical elements of research design such as provision of childcare, refreshments, and payment of community co-producers, all of which are key to facilitating the more equal participation of potentially marginalised groups.

For this project, therefore, lunch and refreshments were provided; we were flexible about bringing along children; and the women who collaborated were appropriately compensated. Following our initial workshops, we kept in touch via a WhatsApp group. Paying careful attention to these practicalities was vital to the success of the project.

Getting the message right

A further challenge of co-production is establishing the main message of the output whilst still ensuring that everyone has space to share their ideas and stories.

To manage this, I led a series of activities structured around broad themes – life in Colombia, the migration journey, life in Chile, future aspirations – to allow co-producers to choose the specific issues that they wanted to focus on. I experimented with different activity formats to give everyone a space to participate, whether they preferred talking one-to-one, as a group, or expressing themselves visually. One of the most successful activities involved dividing up into small groups to create and present maps that represented the women’s migration journeys from Colombia to Chile. Full-group discussions worked less well, as it was harder to stay on track and manage our time.

What surprised me most was the consensus that emerged on the tone that co-producers wanted the video to adopt. While we might immediately think of arduous and dangerous journeys over land from Colombia to Chile; hostile and obstructive border police; or stigmatisation in an adoptive country, the co-production process revealed also the women’s pride in their determination and optimism against all odds, their desire to evoke and share the beauty and vibrancy of their homeland.

Alice was able to capture this perfectly in her visual representations, which were met with resounding approval. If I had been analysing fieldnotes and interviews, would the centrality and energy of this message have shone through so clearly?

Such are the valuable and humbling lessons of arts-based research co-production.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Follow Dr Megan Ryburn on Twitter at: @M_Ryburn

• Read more about the Navigating Borderlands project on our website

• Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identity of research participants

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

This is excellent. I am leading a strategy to create an animation super cluster in Ireland and am in the process of getting the participating groups to identify key themes. The primary one we are focusing on is ESG and your animations and paper is a fabulous example.