The idea of Chile as a “free market miracle” is one of the most powerful myths in the recent history of economic development, but Chile’s export diversification was really the result of carefully crafted government interventions, writes Amir Lebdioui (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

The idea of Chile as a “free market miracle” is one of the most powerful myths in the recent history of economic development, but Chile’s export diversification was really the result of carefully crafted government interventions, writes Amir Lebdioui (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

• Disponible también en español

• Também disponível em português

Assessing industrial policies in Chile remains a contentious and divisive topic. Chile has long been held up as an almost textbook example of the success of “letting the market do its work”, as there was a broad agreement among mainstream economists that Chile had largely succeeded in promoting strong and stable growth because it had embraced free market policies.

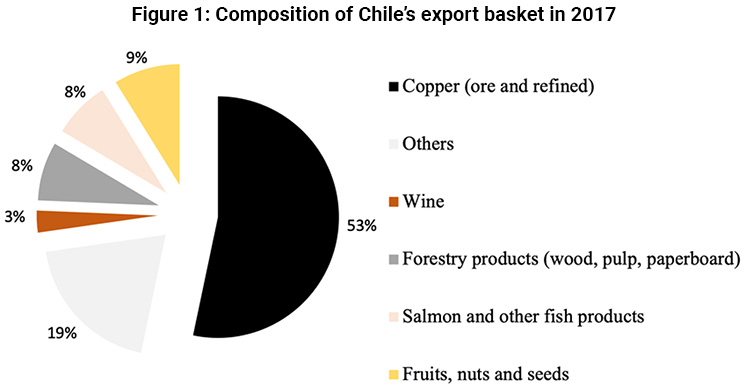

At first glance, this may seem believable. After all, Chile has had one of the fastest growth rates in Latin America since its neoliberal turn in the 1970s. Despite the continuing significance of copper, it also managed to diversify into other sectors and acquire new competitive advantages between the 1960s and 1990s. The dominant view sustains that the successful emergence of new competitive sectors in Chile’s export basket is the result of four decades of commitment to liberalisation and free market policies.

However, as I argue in a recent article for Development and Change, Chile’s export diversification was not the result of free market policies, but rather of carefully crafted government interventions. The idea of Chile as a “free market miracle”, first advanced by Milton Friedman, is therefore one of the most enduring myths associated with recent economic development history.

Source: UN COMTRADE (2019)

The invisible hand on the steering wheel?

Chile is often viewed by admirers and critics alike as the quintessential neoliberal model of development in Latin America, as it became the first country in the region to embrace neoliberalism following the 1973 coup against Allende’s socialist government. The Pinochet administration was explicit in stating that the government avoided picking winners by “letting the market choose”, thereby invoking the logic of the Chicago School. But it was also discreetly – yet heavily – involved in subsidising the structural transformation of the Chilean economy, intervening in almost all the major sectors that have emerged in Chile’s export basket since the 1970s (illustrated in figure 1, above).

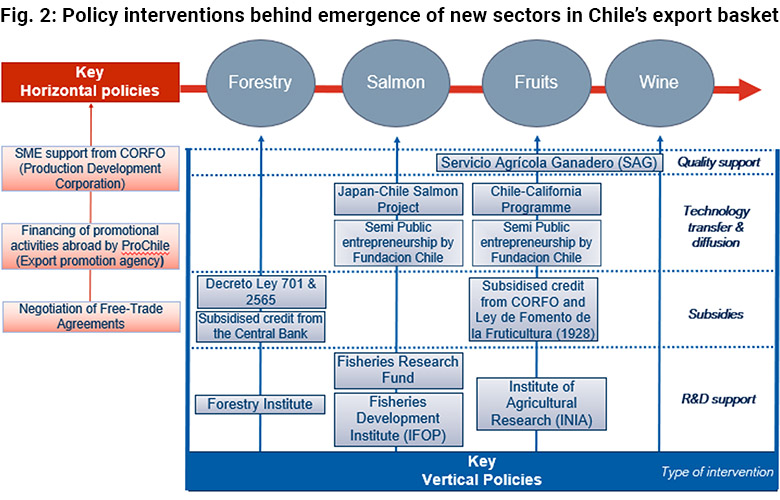

Figure 2 highlights the vertical policies that belied this claim of sector neutrality and the role played by various types of public institutions (including government agencies, the Central Bank, and universities) in the process of capability accumulation and in overcoming market failures inhibiting the emergence of new industries.

In contrast to the widespread laissez faire narrative, industrial policies were used to effectively govern the market by sending market signals towards new areas where private entrepreneurship had been suboptimal. The role of the Chilean state was essential in catalysing human capital accumulation, ensuring “national” sector reputation through strong regulatory and quality control, providing semi-public venture capitalism, and diffusing expertise and technology in non‐copper sectors through various public institutions. Interventions even included the provision of subsidised credits through the Central Bank and CORFO (especially in the forestry and fruit sectors).

The opening up of the economy in the 1980s later took advantage of the specialised human capital, knowledge and technological capabilities accumulated through vertical interventions prior to liberalisation. While it can be argued that some sectors, such as the wine industry, could have developed through market forces alone, it is undeniable that other sectors would not have developed to the same extent without vertical interventions – in fact, it is likely that some would not have developed at all, given the policy‐induced endowments for the forestry and salmon sectors.

The comparative advantage that Chile developed in salmon, forestry, and fruit production did not simply rely on natural factors; rather, it has mostly been acquired through technology upgrades, human capital accumulation, export quality control, and financial incentives – that is, through state interventions. In addition, while the wine sector’s technological upgrading was mostly the result of foreign investments and horizontal policies (unlike in other sectors), it is worth noting that those foreign investments targeted an industry in which Chile was already operating, and as such they did not promote a new product beyond Chile’s pre-existing productive structures.

Furthermore, in contrast to the sectors that relied on state interventions, value addition has been relatively weak in areas where the state adopted a more laissez faire approach, such as the copper sector. Another recent study found that the industrial fabric around Chilean copper is weak in comparison to those found in other resource-rich countries such as Australia and Malaysia, where industrial policies were heavily used to promote both downstream and upstream value addition.

Nevertheless, it would be misleading to think that industrial policy was a consistent feature of Pinochet’s economic policy. The regime’s shock therapy in the mid‐1970s – eliminating price controls, cutting public expenditure in half, privatising hundreds of state‐owned firms, drastic reductions in import tariffs – sent the country spiralling into a financial crisis within a few years. It also led to a steep increase in non‐traditional imports and a drop in imports of equipment and machinery, which failed to raise productive investment and recover the growth rates of the 1960s. Free market policies also resulted in financial and balance-of-payments problems before the 1982 debt crisis, which may explain why the military regime increasingly relied on industrial policies thereafter.

Abandonment of industrial policies, export concentration, and commodity dependence in Chile

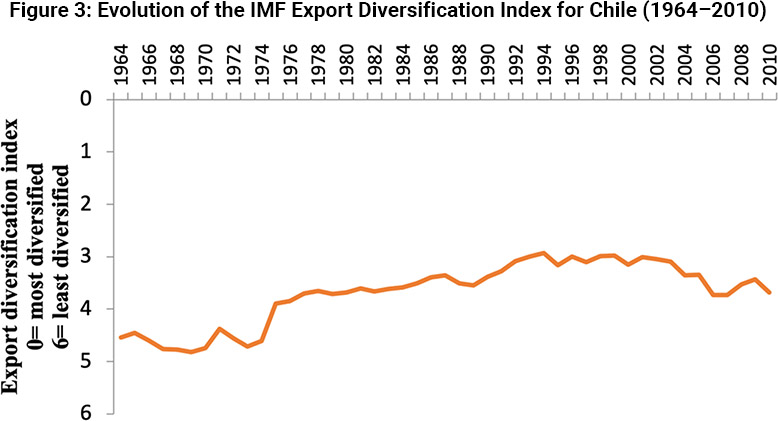

While some of the most successful vertical policy instruments were used during the seemingly economically liberal military regime (1973-1990), the progressive abandonment of those policy tools from the 1990s onwards correlates with a decreasing degree of export diversification.

Since 1990, the new political economy has been rooted in neoliberal fundamentals, with a policy consensus that economic growth is based on ensuring macroeconomic stability (low inflation, low fiscal deficits, and moderate current account deficits) and a view of industrial policy as unnecessary or unproductive. Economic policy has also focused on natural comparative advantages, which give more importance to natural resource endowments than to potential capabilities accumulation, learning by doing, and incremental innovation in new industrial sectors.

While focusing on sectors strictly related to resource endowment is sensible, it should not prevent strategic gambles beyond a country’s comparative advantage. While it is true that Chile has been one of Latin America’s fastest growing economies in recent decades, we must acknowledge that such growth since 1990 has owed much to high copper prices. Indeed, Chile’s growth began to slow in 2014. Between 2014 and 2019, Chile’s average GDP growth dropped below 2.0% (and hit 1.0% in 2019), placing it 17th amongst 33 Latin American and Caribbean economies.

The fact that Chile’s recent export concentration has eventually translated into slower economic growth shows that “adhering strictly to macroeconomic fundamentals is not enough to ensure steady high-end economic growth when sector-specific weaknesses are not addressed”. Numerous Chilean economists (such as Manuel Agosín, José Miguel Ahumada, Claudio Bravo-Ortega, Ricardo Ffrench-Davis, Nicolas Grau, Gabriel Palma, Andres Solimano) have produced seminal works along these lines, critically analysing the role of state interventions and the limits of the neoliberal model in Chile.

Why it matters for today’s Chile

Over the past decade, Chile has been shaken by waves of social unrest, which culminated with the 2019 protests. Such protests were motivated by the perception of growing inequality and have generated considerable political and economic instability. Chile’s unequal distribution of income is also intrinsically related to the growing concentration of its productive structures.

A new model is therefore urgently needed to diversify the Chilean economy, create jobs, and reduce inequalities. Such a model would require the return of industrial policy to the forefront of the policy agenda. Improving the pre-distribution of income would indeed require coordination between industrial, social, and education policies to generate demand for workers with newly acquired skills.

Industrial policies will also be needed to make the most of lithium resources as a tool for productive development. Some of the mistakes from the copper sector, like limited state intervention to promote value addition, should be avoided as lithium provides an opportunity for Chile to get ahead in the technological race.

The current quest for a different development model in Chile represents an opportunity to rethink the role of state intervention. As we can learn from the East Asian Miracle and from Chile’s own history, elements like targeted human capital accumulation, technological diffusion, R&D support, and environmental sustainability are crucial for the acquisition of new comparative advantages, but they are also difficult to manage without policy interventions.

Debunking the myth of Chile’s neoliberal solutions therefore helps not only to provide a more nuanced narrative of Chile’s economic past but also to shape the country’s future.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article is a lightly edited version of a post originally published by Developing Economics

• This site’s usual Creative Commons licence does not apply to this content

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Given the preponderance of copper in exports, I would suggest that Chile was faced with a Dutch disease-type situation. A *purely* free-market response would likely have pushed investment into non-tradeables. But what we saw was an industrial policy that provides market incentives for exportable sectors, rather than one characterized by state investment. There is an important distinction here.

I had the opportunity to interview the President of Quito-based Banco de los Andes in 1989. His wife was Chilean, and he traveled there annually. He told me, “I used to tell people in Chile that I was from Ecuador, and they would say something like, “How nice”. Now, I tell them I am from Ecuador, and they ask, “What can we sell there.”

Highlighting the role of industrial policy in 1980s Chile is a worthwhile contribution. However, the author draws too sharp a distinction between state and market, and the real change in mentality from inward-looking to outward-looking.