‘Today, we tell the despotic regime in Saudi Arabia that we will not be part of their military adventurism’, said Senator Bernie Sanders on 13 December 2018, as the Senate voted to end U.S military support for Saudi Arabia’s conflict in Yemen. Despite bipartisan support for this resolution, passing in both the Senate in March and the House just one month later, US President Donald Trump vetoed the measure in April, saying that the United States ‘cannot end the conflict in Yemen through political documents’, and describing the resolution as ‘an unnecessary, dangerous attempt to weaken [Trump’s] constitutional authorities’. While the veto puts him at odds with the American legislative branch, Trump’s continued support for Saudi Arabia has followed a historically consistent, strategic pattern in the Middle East.

The Middle East has long been a region of interest for the United States since the Cold War. Israel received significant American aid throughout the Arab-Israeli clashes. In 1957, the American condemnation of the joint British and French invasion during the Suez Crisis ended the lingering remnants of European influence in the Middle East. Later initiatives, such as Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy in 1974, the Camp David Accords in 1978, and the Madrid Conference 1991 allowed the United States to assume an active role in reducing tensions in the Middle East.

Yet for all its activism in the region, the United States has seldom participated in regional conflicts directly. Interventions in Lebanon in 1958 and 1983, participation in the first Gulf War in 1991, and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003 respectively prove to be exceptions rather than the norm. Instead, the United States prefers to be an indirect actor in the region, providing financial aid and arms to its allies. Exerting indirect American influence through proxy warfare is nothing new to the United States. Under the Nixon administration, military aid to Israel grew from $30 million into an astonishing $2.5 billion between 1970 and 1974. The primary function of funding the Israelis was to combat Soviet-sponsored Arab states in the region, while simultaneously containing Arab nationalism that it could not completely control. The Arab-Israeli conflict in the 1970s was a regional microcosm of the U.S struggle for influence during the Cold War, and also an example of indirect American involvement as a primary strategy in the Middle East by supporting states like Israel and Iran.

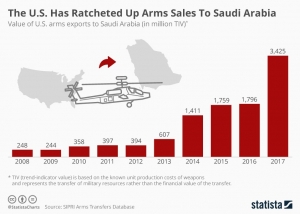

American usage of proxy warfare in the Middle East, however, has continued into the twenty-first century, with some irony, against its former ally in Iran. In Yemen, Saudi Arabia has been militarily involved in fighting the Iranian-backed Houthi movement since 2015. In an attempt to bring the ousted Hadi government back into power, a Saudi-led coalition has escalated the civil war in Yemen. American military support for the Saudis played a significant role here, as the United States refueled Saudi planes and provided them with bombs until last November. While not directly involved in the conflict, the United States also sold a vast amount of arms to Saudi Arabia, totaling approximately $9 billion from 2013 to 2017. Last year, the United States cleared arms deals with the Saudis valued at $18 billion – double the combined sales of the previous four years. Although arms sales alone do not correlate to proxy warfare on the United States’ part, funding the Saudis and the current state of U.S-Iranian relations suggests a connection between American strategy and its geopolitical objectives.

The Trump administration has expressed a clear alignment towards Saudi Arabia, while confronting Iran with a “maximum pressure” strategy. Supporting Saudi efforts in Yemen shows America’s goal of reducing Iran’s influence in the Middle East and pushing back against the Iranians on several fronts. Since taking office, the Trump administration has undertaken a series of diplomatic actions against Iran. The withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal last May, the re-imposition of sanctions in August (which came into effect in November), and the termination of the 1955 Treaty of Amity (in October) suggest a broader pattern of deepening American-Iranian hostilities. This June, the Trump administration confronted Iran with a new series of sanctions, continuing American pressure on the Iranian government. Combined with proxy support for the Saudis in Yemen, this allows the United States to take advantage of pre-existing tensions in the Saudi-Iranian relationship to advance its geopolitical ambitions.

The parallels between the two cases, however, are not as striking as they appear. Saudi Arabia does not enjoy the same level of support that Israel had from American public opinion. As the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi last October demonstrates, there are continuous tensions that exist between Trump’s continued support for the Saudis and domestic calls to condemn Saudi actions. Just recently, Congress voted to block emergency arms sales to Saudi Arabia, demonstrating an ongoing challenge to the Trump administration’s continued support of a controversial ally. Unlike Israel in the 1970s, Saudi Arabia is also not surrounded by hostile states. As one of the largest economies in the world, Saudi Arabia enjoys a degree of stability and is bolstered by its participation in international organizations such as the G20. Despite different circumstances, Trump’s choice to support the Saudis is not out of line when considering American involvement in the past.

The longevity of proxy warfare as a part of American military strategy shows an appreciation for indirect intervention into conflict. It allows the United States to influence regional disputes that contain larger implications of geopolitical control, as seen in the 1970s Arab-Israeli conflict. By supporting the Saudis in Yemen, the United States can have its ally contest the Iranian influence regionally, while using a series of diplomatic and economic maneuvers to weaken Iran’s geopolitical influence in the Middle East. This ensures a stronger Saudi Arabia in the region; an actor friendly to the United States, and a maximization of American influence in the region without direct intervention.

Employing proxy warfare as a dominant strategy holds attractive prospects for American policymakers. It allows for a continued projection of American power, albeit in a less direct manner. The United States enjoys greater flexibility in helping its regional allies fight its battles. Not only can it influence the measures undertaken by its allies in these conflicts, but it also economically profits from arms sales. The implications of retaining proxy warfare in favour of direct interventions seem conducive to American interests as well. The United States reaps benefits without having to deal with domestically worrying consequences such as American casualties and deaths. The Vietnam War, for instance, would have made any further troop deployments nearly impossible, especially with defense budget reductions in the 1970s. Despite American military spending slowly growing in recent years, employing American troops abroad is no easy task, considering the legacies in Iraq and the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan. In these contexts, the case for using proxies was, and still is, increasingly viable as a policy option.

That is not to say proxy warfare is without disadvantages. It is vulnerable to sudden regional shifts, as demonstrated by Egypt and Syria’s surprise attack on Israel in the 1973 October War, prompting the Nixon administration to initiate an emergency airlift to help reinforce its ally. The recent Congress and Senate votes on Yemen are indicative that the United States cannot absolve itself of all responsibility simply by relegating itself as a more secondary actor in a conflict. A heavier reliance on the Saudis runs the risk of unintended developments, as seen by the ongoing humanitarian crisis and famine inside Yemen. The United States may need to adjust goals to match its level of engagement, as American agency is confined to actions that avoid direct intervention.

Despite these risks, an examination of the United States’ strategy in the Middle East strongly hints towards a pattern of continuing indirect conflict by helping its allies and seeing them as proxies. Proxy warfare acts to circumvent these barriers and provide an alternative method of American influence, while strengthening its relations with allies in the Middle East by relying on them to carry out American interests. Shifting from direct to indirect intervention may be a necessary reconciliation between the limitations of American hard power and its goals, but the payoff may be greater in the long-term for the United States, even at the loss of total control.

Angus Lee is a recent graduate from the University of Toronto where he is currently working as a research assistant in the Department of History. He is interested in American foreign policy and strategy, with a particular focus on the Middle East with attention to its regional geopolitics.