While most Indian Citizenship histories reminisce the ‘long fifties’ (1947-1964) to have been an era of liberal triumph, the internment of Chinese Indians uncovers a gloomier past as Noel Mariam unfolds in this article. She argues that the case of Chinese-Indian internment in the post-war period helps trace semblances of how the liberal state mutates in contexts of ‘national security’ crises.

Rarely, if ever, does Nehru’s ham-fisted approach during the 1962 Sino- Indian war escape elision. The dim-witted intelligence gathering, the over-estimation of military capacity and the insistence on ‘diplomatic’ solutions, in hindsight, have sobered his otherwise towering legacy. Whatever the military miscalculations, for those interested in the ruptures of citizenship history, the 1962 War represents a moment of lasting significance, that has hitherto been buried in post-war ‘excuses’. Then Home Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s unironic characterization of “happy internees”, earned plaudits in the Indian parliament in the 1960s.[1] Ensuing nationalist rationalizations termed the internment of Chinese Indians as a ‘necessary evil’. Early on, even academic consensus heralded this era of Nehruvian leadership (1947-1964) – ‘the long 50s’ – as a period of national flourishing, when citizenship was rerouted from the history of both Colonialism and the Partition. However, this self-congratulatory reading of history did not look at how ‘citizenship’ was made and unmade differently for different communities.

Scholarly interrogation of the internment of Chinese Indians is recent.[2] This piece probes this phenomenon as an event that illuminates the illiberalism of the early postcolonial state. First, it exposes state misrecognition of Chinese Indians as “enemy aliens” to be intimately tied to colonial continuities.[3] Second, postcolonial refashioning of colonial laws demanded state paraphernalia functioned uncontested and in collective sync. A silent supreme court, coordinated efforts of the Ministries of External, Home and Defense and an army that overstepped jurisdictions to help the police identify, round up and transport internees to camps – all worked together towards a protracted emergency for Chinese Indians. Hence, this internment, at the peak of Indian self-fashioning as a liberal democracy, uncovers how colonial legacy metamorphized in counterintuitive ways, amidst emerging national antagonisms.

Colonial Ancestry

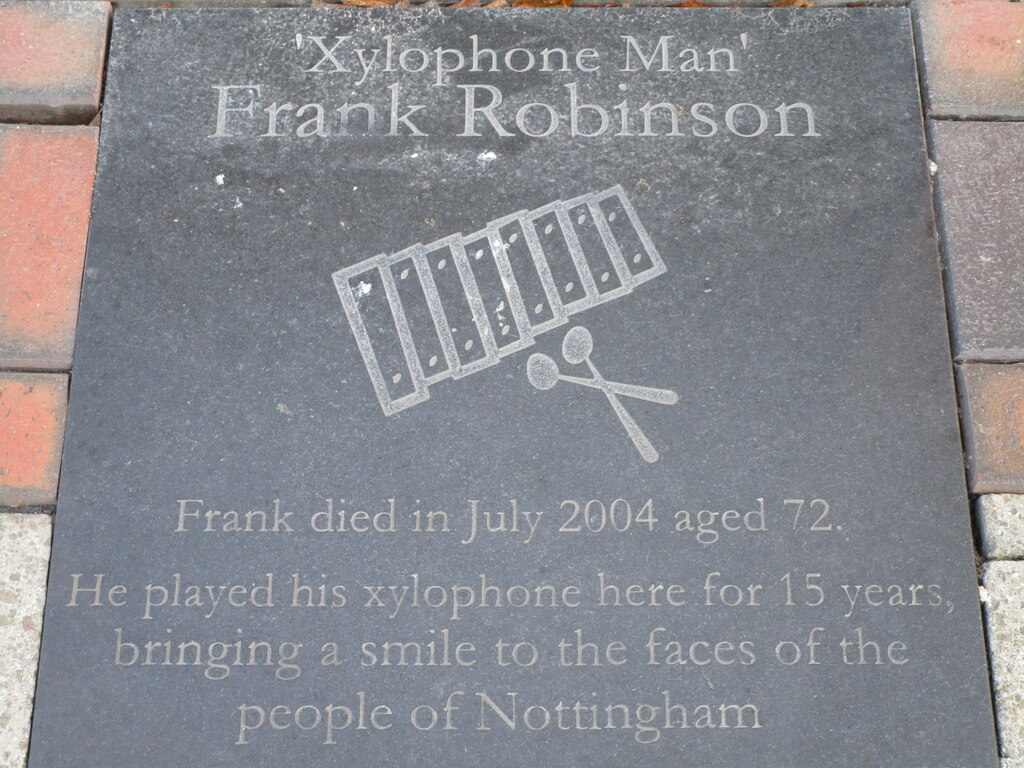

Restrictions on Chinese mobility in India have clear colonial precedence. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 necessitated all Chinese immigrants to obtain a license to enter or work in India and also placed restrictions on the number of Chinese that could enter each year.[4] The British saw the Chinese as a threat to their economic interests and as early as 1905, when they established a “Chinese Protectorate” in Calcutta to further regulate the entry of Chinese immigrants into British India. Despite this, in the mid-20th century, Calcutta still bustled with Chinese leather workers, chefs and restaurant owners. In 1942, the colonial government interned several communities whom they suspected to be sympathizers of Axis powers– Germans, Italians and Japanese. After the Japanese invaded Burma and threatened to march into India, a slew of colonial laws were unleashed, suspending all rights of ‘foreigners’, among who were suspected Chinese nationals. [5] As per the demands of the Passport Act of 1920, the state on short notice demanded passports and criminalized those who did not possess one as “prohibited immigrants”.[6] The Foreigners Act, 1946, which evolved from the Indian Immigration Act, 1908; was revived to detain ‘aliens’ en masse without due process during the internment.[7] After Indian Independence in 1947, the , the Defense of India Rules (DIR) was initially repealed. However, they were revived in 1962 during the Sino-Indian war. This sanctioned an informal emergency and the restriction of ‘foreign’ subjects in detention camps, the largest of which was in Deoli, Rajasthan.[8]

Post-Colonial Refashioning

In 1962, when Chinese Indians were interned by the supposedly anti-imperial liberal state, strikingly even the camp did not change, excluding the legal apparatus that ratified the suspension of all rights. This time, the Passport Act of 1920 and the amended Foreigners Act of 1962 and 1964 along with the notorious Defense of India Rules, 1962 were aggregated to create a state of exception for select citizens of the country. While the majority of Chinese Indians were held between 3-5 years, there were circumstances when “suspicious” internees were put through the ordeal for up to 7 years.[9] Along with interning a significant chunk of the population, the state also regulated Chinese movement, imposed censorship on those reporting human rights violations, oversaw the functioning of Chinese-owned enterprises and even controlled the supply of essential commodities. The internment reinforced Independent India’s reliance on the colonial legal apparatus, which had, only in the recent past been ironically used to suppress the rights of Indian colonial subjects.

However, internment did not earn universal consensus in the parliament. It brought together a constellation of critics – Hiren Mukerjee, a prominent communist leader; Atal Bihari Vajpayee, leader of the Hindu Nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, and Ram Manohar Lohia, an ex-Congress leader who, disenchanted began the Socialist Party of India. Nehru’s beloved daughter Indira Gandhi herself, as surreal as it would seem, came in the defence of the civil and political rights of Chinese internees.[10] As for Nehru, he asserted time and again that the internment was not a “punitive measure” on basis of ethnicity, but a temporary suspension until the cessation of national hostilities.[11] Here, he constructed national differences, even of innocent citizens, as a threat to national security. Notwithstanding the ‘liberal’ leaders’ justifications, the internment allowed for an explosion of the deep-seated anti-Chinese sentiment in Indian society. It marked a lasting scar on the Chinese-Indian memory, an alienation from a place they had for decades considered home. After the war, both India and China sat down for repatriation agreements. The repatriations were carried out along the border crossing points of Nathu La and Shipki La in the Himalayas, amidst continued border tensions. The repatriates had no choice in either case. Amidst warmongering, both countries refused to address the treatment of civilians during the war. In India, it solidified the precarity of civic citizenship for people of Chinese origin, despite India’s rhetorical adherence to liberal principles.

Indian citizenship and parallel state practices have been projected to be overwhelmingly liberal, especially in the early years after decolonization, except for the occasional moments it came adrift. The Chinese Indian internment, in this narrative, has been warranted as an anomaly, an unfortunate blot in citizenship history. Rather than dismissing the internment as circumstantial, an unmasking of the colonial continuities in state persecution, helps trace semblances of how the liberal state mutates in contexts of ‘national security’ crises. Moving away from narratives that ignore ‘anomalies’, the article attempted to lay pointers to how the suspension of the rights of targeted citizenry, has not been few and far between. ‘Exceptional’ legal apparatuses were resurrected during the Indo-Pakistan War (1965), the Emergency (1975-77), the Khalistan Movement (different times in the 1980s) and the Kargil War (1999). With this hindsight, the Chinese Indian internment brings to the fore, the totalitarian inclinations of the postcolonial state and possibly, the limits of liberalism in contexts of War.

Featured image: Internment Camp at Deoli, taken from indiadeoli.wordpress.com

[1] “Shastri Finds Chinese Internees Happy: Cordial Scenes on his visit to Deoli.” 1963.The Times of India (1861-2010), Jun 10, 1.

[2]Banerjee, Payal. “Chinese-Indians in Fire: Refractions of Ethnicity, Gender, Sexuality and Citizenship in Post-Colonial India’s Memories of the Sino-Indian War.” China Report 43, no. 4 (2007): 437-463.; Banerjee, Payal. “The Chinese in India: internment, nationalism, and the embodied imprints of state action.” In The Sino-Indian War of 1962, pp. 225-242. Routledge India, 2016.; Marsh, Yin. Doing time with Nehru: The story of an Indian-Chinese family. Zubaan, 2016.; Ma, Joy, and Dilip D’Souza. The Deoliwallahs. Pan Macmillan, 2020.

[3] “The Enemy Property Act, 1962,” Section 2 and 3, Abhilekh; National Archives of India, accessed on Feb 27, 2023Abhilekh Patal (abhilekh-patal.in)

[4] Correspondence from Inspector General of Police, Calcutta to the Chief Secretary, Government of Bengal; Report on the Control of Chinese Immigration in India, L/AG/30/32/74. 28 August 1939. UK National Archives, London

[5]Correspondence between the War Office and the Colonial Office regarding the internment of Chinese Nationals during World War 2, War Office: Prisoners of War and Internees Department: Registered Papers (Series II), WO 208/327. November 1941. UK National Archives, London

[6] “Power to Require Passport, Section 3, Passport Act of 1920.” Abhilekh: National Archives of India, accessed on March 2, 2023, Abhilekh Patal (abhilekh-patal.in)

[8] “Defense of India Rules, 1962.” Government of India. Ministry of Home Affairs. Gazette of India, extraordinary, Part II, section 3(ii), June 7, 1962.

[9] “File no. 181/5/62-CI: Correspondence and Case Files of Chinese Internees, 1962-1964,” Papers relating to internment Camps in India, 1941-1946, National Archives of India, New Delhi

[10] Gandhi, Indira. “Chinese Nationals in India (Internment).” Parliamentary Debates, Rajya Sabha, 3rd session, vol.15, no.5, Aug. 1962, pp. 5345-48

[11] Nehru, Jawaharlal. “Chinese Nationals in India.” Parliamentray Debates, Lok Sabha, 3rd session vol.29, no.14, Aug.1963, pp.15660-15668,